To mark the anniversary of Martin Carter’s passing on December 13, 1997, Gemma Robinson looks at Carter’s Poems of Succession, published 40 years ago this year.

Gemma Robinson works at the University of Stirling, Scotland and is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).

Information about The George Padmore Institute can be found at

http://www.georgepadmoreinstitute.org/

The Terror and the Time can be viewed here:

https://archive.org/details/XFR_2013-08-07_2A_02

https://archive.org/details/XFR_2013-08-07_2A_03

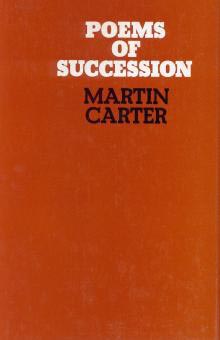

2017 is a year of Martin Carter anniversaries. It is 90 years since his birth in 1927, 40 years since the publication of Poems of Succession, and 20 years today since his passing. Through this passage of time, we can now look back at Carter’s poetic career and see a triptych of work in Poems of Resistance (1954), Poems of Succession (1977) and Poems of Affinity (1980). More than any of the collections, Poems of Succession has a history full of twists and turns, and this knotted journey to publication can tell us much about Carter’s poetic interests, and how they reverberate for us today.

In the period between Carter’s Jail Me Quickly (1966) and Poems of Succession, Guyana had declared its political independence, and Carter had been appointed to and resigned as Minister of Information and Culture in the PNC government. A spirit of re-examination pervades Poems of Succession, an approach pointed to in the title. ‘Succession’ is a suggestively political term, acting as a reminder that Carter now writes from within the independent ‘succession state’ of Guyana. But the implied ‘success’ of this independence is altered by the publication date: Poems of Succession appeared in 1977, a full 11 eleven years later, and cannot be read as an immediately celebratory text for independence. The implications of ‘succession’ must be viewed as multiple. Carter gathers a selection of poetry, both published and unpublished from the 1950s to the 1970s. The published poems of ‘resistance’ from the 1950s stand alongside poems of the 1960s and 1970s, asserting the painful ‘successions’ of Guyanese history.

In 1969, C L R James wrote to Carter, then still Minister of Information and Culture: “I hope you have not entirely abandoned the writing of poetry”. He had not, but poems appeared only sporadically in journals and the Guyanese press: notably, GISRA, Savacou, Kaie and The Sunday Chronicle. That same year Carter had invited John La Rose (the Trinidadian writer and the founder of New Beacon publishers based in London) to the Caribbean Writers and Artists’ Convention in Georgetown. At the convention, Carter discussed with him the possibility of New Beacon publishing a retrospective collection of poems. La Rose agreed and Carter gave him the provisional title, Poems 1970-1950, destabilising the standard chronological understanding of a writer’s work.

The George Padmore Institute in London now holds the papers related to the publication on Poems of Succession. In it are rare notes and correspondence from Carter. About this collection, Carter was firm: “And the order in which [the poems] are set out is not the chronological order in which they were made. Just the opposite”. What we are to learn by reading from present to past is not stated, but the pull towards making sense of time is always in Carter’s sights, as his poetry seeks to understand the colonial past of enslavement alongside the disruptive, decolonising present and future. One of the key ways this translates into his work is through fragmentary aphorisms. “The terror and the time” from ‘University of Hunger’ is one of the most powerful of these phrases. The Terror and the Time is also the evocative title of the Victor Jara Film Collective’s sharp-eyed lyrical documentary of the 1953 Emergency and contemporary Guyanese politics, which premiered in the same year (1977 dir Rupert Roopnaraine), and shares Carter’s focus on how to speak and act in the long duration of ‘repressive violence’.

The George Padmore Institute in London now holds the papers related to the publication on Poems of Succession. In it are rare notes and correspondence from Carter. About this collection, Carter was firm: “And the order in which [the poems] are set out is not the chronological order in which they were made. Just the opposite”. What we are to learn by reading from present to past is not stated, but the pull towards making sense of time is always in Carter’s sights, as his poetry seeks to understand the colonial past of enslavement alongside the disruptive, decolonising present and future. One of the key ways this translates into his work is through fragmentary aphorisms. “The terror and the time” from ‘University of Hunger’ is one of the most powerful of these phrases. The Terror and the Time is also the evocative title of the Victor Jara Film Collective’s sharp-eyed lyrical documentary of the 1953 Emergency and contemporary Guyanese politics, which premiered in the same year (1977 dir Rupert Roopnaraine), and shares Carter’s focus on how to speak and act in the long duration of ‘repressive violence’.

Five years passed and Carter had not settled on the collection. La Rose repeated his offer of a ten per cent royalty, with an advance fee of £20. After multiple promptings, and during a writing residency at the University of Essex in 1975, Carter wrote to La Rose about ‘Poems of Succession’, sketching what the book cover might look like. Countering La Rose’s suggestion of asking Aubrey Williams to design the cover, Carter wrote: “Perhaps a plain self-colour – rust red with the title in small black print might be best”. It is intriguing to think what the great colourist, Williams, might have done for the collection and telling also that Carter favoured simplicity in colour and font for his most large-scale work.

There may have been a further consideration about the title: in his Brown Notebook on the year planner for 1976, next to the address of New Beacon Books, Carter wrote: ‘POEMS OF REVISION’. Nothing came of this, but the retrospective collection of poems was certainly a significant reimagining of the earlier idea, and Poems 1970-1950 was folded into a new vision: Poems of Succession. Rather than emphasising earlier work, the final collection was distinguished by its inclusion of new work. ‘The When Time’ – the name given to the newly published work – takes up a third of the book and the dates of composition which appear by each new poem prove the continued poetic activity of Carter between the 1950s and 1970s.

Poems of Succession has been described by Rupert Roopnaraine as a collection of “private wonder”. It is certainly this, and in its poetic range we find a body of work that progresses out of the personal into complicated affiliations. ‘For Milton Williams’ sees Carter address the concrete geography of Guyana and a particular Guyanese friendship: “Rivers that flow up mountains are to you / what streets there are, inevitable pathways”. ‘For Angela Davis’ praises the revolutionary work of the African-American activist, and attempts to explain her importance within the poet’s life: “the / power of love you cherish / which so much overwhelms my tongue / given to speech / in the necessary workplaces / where freedom is obscene”. In the poem Carter explicitly sees Davis’s work as a sign of hope and the concluding flood imagery of his Conversations poems is replaced by another covenant:

what I want to do

is to command the drying pools of rain

to wet your tired feet and

lift your face

to the gift of the roof of

clouds we owe you.

Here the cyclical everyday aftermath of tropical rain is invested with a power to restore and connect human endeavour across the Americas.

The task Carter sets himself in ‘The When Time’ involves both asking questions (when?) and making assertions (about the ‘time’). It is tempting to understand the phrase as a euphemism for social revolution. Karl Marx can be read as fundamentally concerned about ‘the when time’ – the moment when the development of historical forces reaches an appropriate time for revolution. But Carter does not use Marx’s terms, nor write in the clarificatory register of political theory. As the syntactical structure of the phrase, ‘The When Time’, shows, Carter’s poetic language stretches us to consider definition, ambiguity and complexity. The phrase draws on but is not written in Guyanese Creole. Richard Allsopp in The Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage picks out ‘when time’ as a phrase used in Barbados, Trinidad and Guyana that emphasises the time when opportunity arises, giving this example from speech: but you will see, when time, he go an[d] marry somebody else. We hear in these two words a sense of promise and fulfilment, but the example shows that the phrase does not necessarily pick out favourable futures. To the ear, ‘when time’ might also seem close to ‘one-time’, the Creole phrase that can voice what happened in the past and an instant moment when an action is completed without hesitation.

Perhaps because of the dense linguistic possibility in the phrase, ‘The When Time’, there is much to be gained from viewing the whole collection as a journey into language, not as retreat from the world, but as a way to emphasise our human need to make sense of it. Carter’s poetic interests and successes are wide – from the grammatical experimentation with colons to produce emphatic punctuation, to his continued concerns to produce a poetry located within, but not confined to, Guyanese society and topography. ‘In the When Time’ (a title poem of sorts) Carter uses the phrase to refer to a particular period, but this is not an easy reference: “In the when time of the lost search / behind the treasure of the tree’s rooted / and abstract past of a dead seed: / in that time is the discovery”. Locating yourself in time and place in this world is no straightforward matter. To search and discover within Carter’s worldview is to spend time with metaphors of time, place and loss.

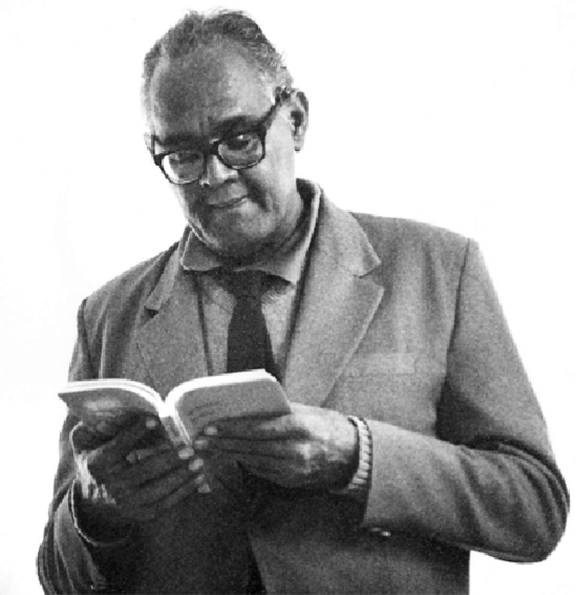

In A Georgetown Journal (1972) Andrew Salkey describes the ministerial Carter, but his assessment of Carter’s relationship to ‘bureaucracy’ and ‘ministerial responsibility’ stands equally well for his relationship to poetry:

“[Carter’s] words were tellingly chosen; his person, a gentle, tall, big man, a poet who may yet do a very serious injury to the sterile vocabulary and syntax of bureaucracy.

“I felt, then, that, if he did succeed in giving something new to the style of his particular ministerial responsibility, not only would it subvert the standard image of the other ministries, for the better, but he would have emerged as the pioneer re-discoverer of the long-lost beating heart in anybody’s politics.”

Salkey suggests that Carter had the potential to alter Guyanese, and regional, politics. Georgetown Journal was published in 1972 by New Beacon, and by this time Salkey would have known the outcome of Carter’s political career in Burnham’s government. The poet who could injure the vocabulary and syntax of bureaucracy did not change it, and Carter resigned.

After his resignation, Carter’s return to Bookers made front-page news in the Sunday Argosy. The period also marked a return to publishing poetry. The first poem was ‘Occasion’, which many of us know better as ‘A Mouth is Always Muzzled’. First published in Georgetown’s Sunday Graphic in early 1971 and then again in Savacou, the poem was quickly interpreted as a statement on Carter’s resignation. He consistently denied that there was an intentional link, describing it as “a general statement”, and arguing that he “had written it before, a long time before” his resignation. Adding to the story Al Creighton writes, “the poem, which is dated [in Poems of Succession] as being written in 1969, was not published at the poet’s instigation at all, but by journalist Ricky Singh acting quite on his own initiative.”

Here is an instance where the publication histories can show how a poem can gain a political urgency. It is also important to see that this poem has multiple published lives: as a stand-alone poem and also as part of ‘The When Time’. Thought of as a ‘when time’ poem, it reverberates with the time of its composition and publication, and with every moment of its reading, including this one and those to come in the future:

In the premises of the tongue

dwells the anarchy of the ear;

In the chaos of the vision

resolution of the purpose.

And I would shout it out differently

if it could be sounded plain;

But a mouth is always muzzled

by the food it eats to live.

Rain was the cause of roofs.

Birth was the cause of beds.

But life is the question asking

what is the way to die.

The neat appearance of the three stanzas, with lines of equal length, highlights the poem’s aphoristic aspirations. Carter’s poem continues to reveal the applicability of Wilson Harris’s statement in Tradition, the Writer and Society (1967) about the writer’s task: “the truth of community which he pursues is not a self-evident fact: it is neither purely circumscribed by nor purely produced by economic circumstance”.

‘A Mouth is Always Muzzled’ faces squarely the economic impediments to truthful or ‘plain’ poetic expression: “a mouth is always muzzled / by the food it eats to live”. However, Carter’s poem goes further than these issues of pragmatics. In exploring apparently clear-cut causal links (“rain was the cause of roofs”), Carter ends with the recognition that thinking about causes will not always offer straightforward systems of relationship. Needing to eat will not always explain why we do not speak. The final sentence is devastating and beautiful: “But life is the question asking / what is the way to die”. On a strictly temporal understanding of causality, life causes death. The lines also allow us to read causality in the opposite direction: the inevitability of death causes us to live asking ourselves how to accept that death.

Carter keeps all these readings open, but what seems most pronounced in the poem is not the causal links between life and death, but the twinning of life and death within a continuing present tense that speaks both of the past and the future. Rereading Carter’s 1977 Poems of Succession, we might conclude that even if we can’t define ‘The When Time’, we can recognise that we are always living within it, anticipating it and remembering it, even as we are straining to understand and define it. The phrase reminds us, as Salkey recognised in Carter, that we can be the “re-discoverer of the long-lost beating heart” of the times we have squandered. And how fortunate we are that Carter found his own ‘when time’ to write these poems.