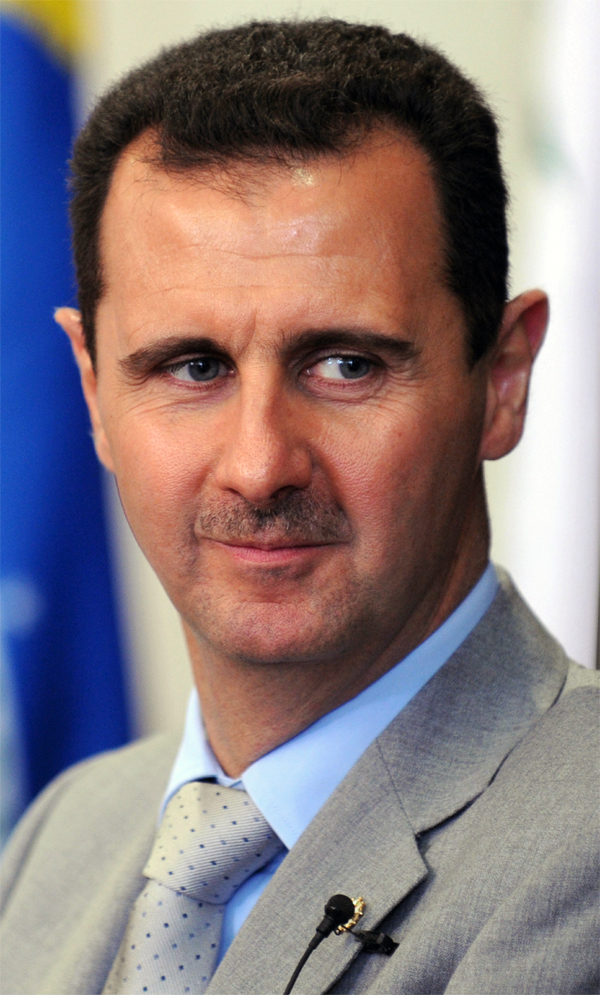

BEIRUT, (Reuters) – With the map of Syria’s conflict decisively redrawn in President Bashar al-Assad’s favour, his Russian allies want to convert military gains into a settlement that stabilises the shattered nation and secures their interests in the region.

A year after the opposition’s defeat in Aleppo, government forces backed by Russia and Iran have recovered large swathes of territory as Islamic State’s “caliphate” collapses.

As U.N.-backed talks in Geneva fail to make any progress, Russia is preparing to launch its own political process in 2018. President Vladimir Putin declared mission accomplished for the military on a visit to Russia’s Syrian air base this week, and said conditions were ripe for a political solution.

Though Washington still insists Assad must go, a senior Syrian opposition figure told Reuters the United States and other governments that have backed the rebellion had finally “surrendered to the Russian vision” on ending the war.

The view in Damascus is that this will preserve Assad as president. A Syrian official in Damascus said “it is clear a track is underway, and the Russians are overseeing it”.

“There is a shift in the path of the crisis in Syria, a shift for the better,” the official said.

But analysts struggle to see how Russian diplomacy can bring lasting peace to Syria, encourage millions of refugees to return, or secure Western reconstruction aid.

There is no sign that Assad is ready to compromise with his opponents. The war has also allowed his other big ally, Iran and its Revolutionary Guard, to expand its regional influence, which Tehran will not want to see diluted by any settlement in Syria.

Having worked closely to secure Assad, Iran and Russia may now differ in ways that could complicate Russian policy.

Assad and his allies now command the single largest chunk of Syria, followed by U.S.-backed Kurdish militias who control much of northern and eastern Syria and are more concerned with shoring up their regional autonomy than fighting Damascus.

Anti-Assad rebels still cling to patches of territory: a corner of the northwest at the Turkish border, a corner of the southwest at the Israeli frontier, and the Eastern Ghouta near Damascus. Eastern Ghouta and the northwest are now in the firing line.

“The Revolutionary Guards clearly feel they have won this war and the hardliners in Iran are not too keen on anything but accommodation with Assad, so on that basis it is a little hard to see that there can be any real progress,” said Rolf Holmboe, a former Danish ambassador to Syria.

“Assad cannot live with a political solution that involves any real power sharing,” said Holmboe. “The solution he could potentially live with is to freeze the situation you have on the ground right now.”

The war has been going Assad’s way since 2015, when Russia sent its air force to help him.

The scales tipped even more his way this year: Russia struck deals with Turkey, the United States and Jordan that contained in the war in the west, indirectly helping Assad’s advances in the east, and Washington pulled military aid from the rebels.

Though Assad seems unbeatable, Western governments still hope to effect change by linking reconstruction aid to a credible political process leading to “a genuine transition”.

While paying lip service to the principle that any peace deal should be concluded under U.N. auspices, Russia aims to convene its own peace congress in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. The aim is to draw up a new constitution followed by elections.

The senior Syrian opposition figure said the United States and other states that had backed their cause – Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Jordan and Turkey – had all given way to Russia. Sochi, not Geneva, would be the focal point for talks.

“This is the way it has been understood from talking to the Americans, the French, the Saudis – all the states,” the opposition figure said. “It is clear that this is the plan, and there is no state that will oppose this … because the entire world is tired of this crisis.”

Proposals include forming a new government to hold elections that would include Syrian refugees.

But “the time frame: six months, two years, three years, all depends on the extent of understanding between the Russians and Americans”, the opposition figure said. “If the Russians and Americans differ greatly, the whole table could be overturned.”

IRAN, RUSSIA DIVERGE ON KURDS

Russia is serious about accomplishing something with the political process, but on its own terms and turf, said senior International Crisis Group analyst Noah Bonsey.

“I am not sure they have a good sense of how to accomplish that and to the extent that they seek to accomplish things politically, they may run into the divergence of interests between themselves and their allies,” he said.

The Syrian Kurdish question is one area where Russia and Iran have signalled different goals.

While a top Iranian official recently said the government would take areas held by the U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led forces, Russia has struck deals with the Kurds and their U.S. sponsors.

“From the start of the crisis, there’s been a difference between the Russians and the Iranians and the regime,” said Fawza Youssef, a top Kurdish politician. The Russians believe the Kurds “have a cause that should be taken into account”.

Damascus, while issuing its own warnings to the Kurds, may continue to leave them to their own devices as it presses campaigns against the last rebel-held pockets of western Syria.

The situation in the southwest is shaped by different factors, namely Israel’s determination to keep Iran-backed forces away from its frontier, which could prompt an Israeli military response.

“There are still major questions and a lot of potential for escalating violence in various parts of Syria,” said Bonsey.