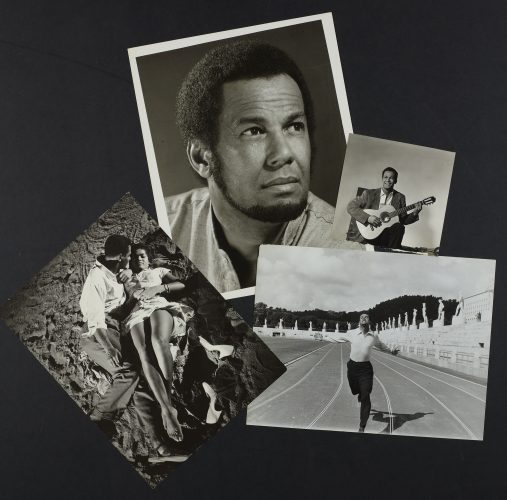

Many knew of the late UK-based Guyanese actor, musician, writer and poet who became the first black person to be featured regularly on television in the United Kingdom, but those who were intimately acquainted with him recall that he was a deeply spiritual man who practiced Tai Chi and meditation every day.

“He was always seen making graceful movements in his garden—it became what his grandchildren knew him for; they simply called him Tai Chi instead of Grandad,” one of his daughters, Sami Moxon, shared with Stabroek News in a recent email interview.

Her sister Dana Grant said that their father, who passed away in February 2010 but whose memory lives on—so much so that he was honoured in the UK recently—was an extremely principled man who always spoke his truth.

“His thirst for knowledge and a deeper understanding of man’s place in the universe drove him forward,” Dana said when asked to describe her father.

“He taught me a lot and encouraged me from an early age to question issues of inequality, greed and exploitation and helped me to develop an awareness of our inter-connectedness and a sense of compassion,” she continued.

Their father, in Moxon’s words, achieved “something remarkable in just about every one of his 90 years. Not only was he an actor, a singer, a writer and an activist, [but] an officer in the RAF (Royal Air Force) [and] a qualified barrister.

Cy Grant, who was bom in Beterverwagting, East Coast Demerara in what was then known as British Guiana, one of seven children for his parents, was himself a father of four—Paul, Dana, Sami and Dominic—from two marriages.

Growing up, Moxon recalled, her father was away a lot while he toured doing Cabaret and various shows.

Dana, Sami and Dominic’s mother hails from Czechoslovakia and Dana revealed that her parents met at a party in London in 1952. Her mom had recently moved to London after being “liberated in the war where she had tragically lost her father and brother who both died in concentration camps.”

She will celebrate her 90th birthday in July; she still lives in the home she shared with Grant and where their three children were brought up.

While their father revisited Guyana “a handful of times” Moxon said, they were all bom in London but never visited Guyana which she described as sad and a “shame.” Grant’s most recent visit to Guyana was in the early 90s when he combined the visit with one to Trinidad during research for his book Ring of Steel.

Speaking about her father as a writer, Moxon said he wrote “prolifically” and for her he had a mind that “was always active even when he was sleeping. He often said that his best ideas came to him at night.”

Love for music

Cy Grant was a man who loved music and he passed this on to his children.

But Dominic—fondly referred to as Dom by his sibling—is the only one of the four who has gone on to make a career of music. He is a guitarist, according to his sister.

Talking about his last days, Moxon said that even though their father was quite ill in his final months amazing things kept happening. “He managed to complete his last book Our Time is Now, which was published just a few weeks before he passed away,” she shared.

Her sister Dana recalled that he was “lucid and writing and working on numerous projects until his final week of life.”

She added that he died with dignity and there was a sense that although he had so much more “that he would have liked to do, he was prepared for death.”

Grant had eight grandchildren and Moxon said he played a major part in their lives and loved to spend time with them. In fact he taught two of her children to play the guitar and her daughter is now in a band.

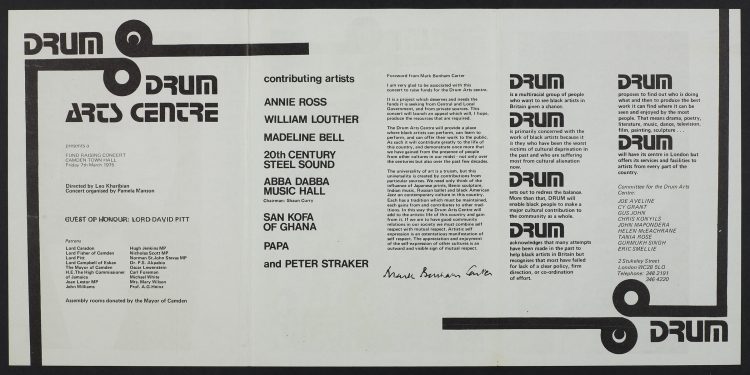

Recently, his work was on display in London through different performances at a free event where workshops, talks, family activities, puppetry, poetry and films were featured. The event, ‘Navigating the Dreams of an Icon: Cy Grant Project Finale’ was held at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA)

“The latest tribute was extremely moving. We are proud that dad’s legacy has been permanently archived,” Moxon said.

“It feels like a huge achievement that his life’s work will now reach a wider audience and as we speak a project pack is being compiled which will form part of the National Curriculum. We are very grateful to our partners the London Metropolitan Archives, the Windrush Foundation and to the Heritage Lottery fund for believing in this project and made it a reality.”

‘Didn’t talk much’

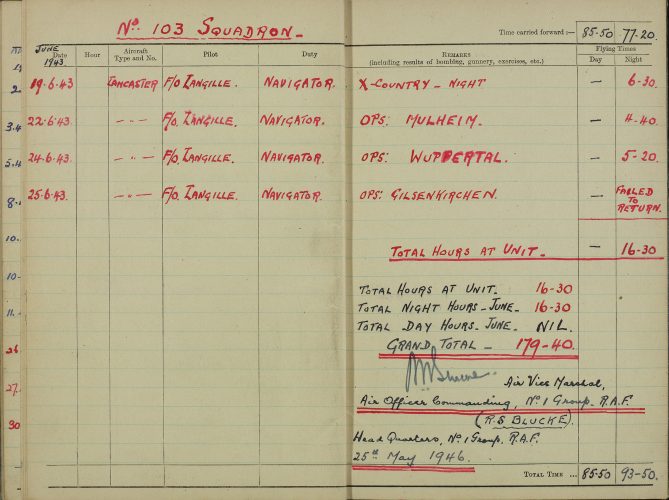

According to an obituary of Grant published in the Stabroek News in February 2010, he left British Guiana for Britain to join the Royal Air Force in 1941, one of some 500 men recruited from the West Indies following huge losses in the Battle of Britain one year earlier and the RAF’s decision to admit non-white aircrew. He trained in England as a navigator and was commissioned as an officer, joining 103 Squadron at Elsham Wolds in Lincoln-shire as Flight Lieutenant Grant and part of the seven-man crew of a Lancaster Bomber.

Moxon recalled that he did not talk much of his time in the RAF and according to her he joined the force “in order to widen his horizons.”

While her father would have been absent from home quite a lot while they grew up, Moxon remembers his returns more than his absences.

“His stories and photos and gifts that he brought back from exotic places… It seemed like a very glamorous job,” she said.

Speaking about her father’s writings, Dana said he often showed her what he was working on and for her “he was like a mentor. He always wrote a diary and had numerous notebooks filled with quotes/ideas/inspirational words.”

Most of his serious writings were done later in his life when she would have already left home, Dana said and as such as a child there is no picture of her father being a writer.

“.. .1 think he did most of his writing in the early hours of the morning. Ideas would often come to him at night and while he meditated.”

About having a famous father, Dana said it was quite fun to see her teachers and friends’ mothers’ reactions to her father.

“He was very popular with women of that generation. I was usually surprised and felt special when people said, ‘Ah! Your dad is Cy Grant!”’

But she said she does not believe he was particularly famous with her generation as they may have just heard of him.

Were they treated like celebrities? “No! But we met a few.”

She shared that the family often had financial insecurity and the worry of “when the next job would come but we always managed…”

Grant was interested in and read on a wide range of subjects particularly racism, spirituality, alternative health, science, eastern philosophy, anthropology, and ancient history Two books that were especially influential and inspiring to him were Lao Tsu’s Tao Te Ching and Aime Cesaire’s Return to my Native Land.

According to the 2010 obituary it was a symbol both of the allure of television and of the way the arts have marginalised black actors that more people above the age of 40 remember Grant only as a singer, broadcaster and recording artist, while those below the age of 40 hardly know much about him.

“Ironically, it is that very process of marginalisation and racial discrimination that Cy spent his entire life in Britain combating. This he saw as a redemptive mission, appealing to white Britain to sweep away notions of cultural supremacy, binary divisions of whites who are indigenous and belong and blacks who don’t, cultures that are mainstream and others that are minority and deemed to be lacking sophistication.”