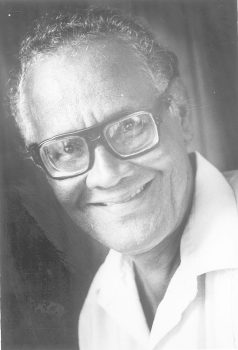

Much tribute is being paid to Martin Wylde Carter (1927 – 1997) around this time, and with very good reason. He holds a highly celebrated place in Guyanese literature. He is popularly referred to as Guyana’s national poet, a title that appears to simply recognise his nationality, but which, in fact, does much more. It is a term of endearment, proclaiming his belonging to the nation and its people. Not only do they claim him as theirs, but do him the greatest honour that they could. With that title they have crowned him with vine leaves of laurel and virtually declared him Poet Laureate.

Much tribute is being paid to Martin Wylde Carter (1927 – 1997) around this time, and with very good reason. He holds a highly celebrated place in Guyanese literature. He is popularly referred to as Guyana’s national poet, a title that appears to simply recognise his nationality, but which, in fact, does much more. It is a term of endearment, proclaiming his belonging to the nation and its people. Not only do they claim him as theirs, but do him the greatest honour that they could. With that title they have crowned him with vine leaves of laurel and virtually declared him Poet Laureate.

Being so designated by the people, it was expected that he would have performed certain functions as poet of the nation, in much the same way an officially appointed Poet Laureate would have done. Closely aligned to this, he has also been called “the Poems Man”, a title that inspired artist Stanley Greaves, a fellow poet with a kindred metaphysical and proletarian spirit. Yet Carter himself was the source of this since it is the title of one of his very significant poems. That poem confirms his popular acclaim, the way people in the streets and villages recognise and acknowledge him.

Still, plain popularity is not what truly distinguishes Carter as national poet. The nation has given him that unofficial crown as a recognition of his greatness. He is acknowledged as Guyana’s best poet to date. The honours roll is not entirely vacant: Leo (Egbert Martin) was the founder of modern Guyanese literature, and contemporary poets like John Agard and, in particular, Mark McWatt have made strides into the top bracket, but Carter dominated the poetry for the decade before and many decades after independence to become the definitive and most identifiable Guyanese poet.

Moreover, what helped to establish him as the greatest was the very manner in which he actually served as national poet without intending to do so. His poetry has virtually documented the story of the nation. In epic Homeric fashion, he has been a griot of history and politics, even if the story he told was a tragic one. Guyana’s foremost female poet, Mahadai Das, expressed the desire to be “A Poetess of My People” in her inaugural nationalistic collection of verse. Carter achieved that role when he called his first collection Poems of Resistance from British Guiana and interrogated Guyana’s political struggles of 1953. He recorded the shock, the tragedy and the grief of racial civil war in the early 1960s, followed by the further disappointment, the greater shock and struggle against the “vileness” in the politics and in the depravity of the human condition during the two decades that followed.

And after all that, Carter’s most compelling achievements as a great artist and as one deserving the high national honour is the extraordinary quality of his verse. Eusi Kwayana (writing as Sidney King) described him as writing “from the profoundly humanist standpoint of the communist”. Eddie Kamau Brathwaite described him as “a poet writing so true” that he defied previously laid down forms of procedure and critical prescription. These were reviews of his early work amidst the misnomer of political poet. But McWatt identified his preoccupation with “state and being” in human existence and his engagement of craft and existentialist concerns were in evidence since his emergence in 1951, while Stewart Brown emphasized the range and depth that characterise his work. There are several very specific Guyanese reference points, but always used as the basis of questioning a universal state. Local political atrocities launch a higher concern for human dignity, questions about human existence, decency and how to live.

Carter had a profound and persistent interest in poetry that made him think like a poet, and reveal thought processes that expressed themselves in poetic terms even in ordinary speech. He once explained, “I never like to publish single poems. Poems should be surrounded by other poems.” True to that, throughout his career he has released poems in groups. Before 1953, for example, in the launching of his career, he published the group of poems The Kind Eagle and The Hill of Fire Glows Red.

The 1950s would have been a fairly quiet period for Guyanese poetry except for AJ Seymour, Wilson Harris and Carter. The last named virtually exploded onto the scene and carried Guyanese poetry with his emphatic arrival. He went on to dominate. After Resistance came another of his characteristic groups: Poems of Shape and Motion. In these, he sought shape and rhythm – he longed for poetic form, in metaphysical fashion studying the “shape”, form and fluidity of fire. Yet, these verses stood out in the Guyanese poetry of the fifties whose main characteristic (except for Harris) was that growing pre-independence nationalism. Even more than Harris, Carter was outstanding in his originality and leadership of poetry even so early in his career. His contribution was the definition given to Guyanese poetry.

Another important group was Jail Me Quickly, which was his response to the violent, bitter and destructive racial uprisings in 1962. These poems which include “Black Friday 1962” demonstrate Carter’s mastery over imagery with some of the most remarkable descriptions in West Indian poetry. They also represent his documentation of critical periods in the nation’s history and how he used them to articulate greater human concerns. Four Poems and Demerara Nigger might have been written in the 1990s and represent one of the poet’s last groups when his mind had moved on even from employing known local launching pads.

In those later years, he told Vanda Radzik, he no longer saw politics as predominant and reflected it in his poetry. He referred to another late poem called “Conjunction” in which he expressed the importance of the word “and” in the way he saw things as conjoined. “It is always something and something else.”

Carter’s particular approach to poetry, language and words was evident when he was asked to speak on differences between poetry and prose. Prose, he said, “begins to continue, while poetry continues to begin.” That very profound definition of poetry is actually demonstrated in his poem titled “Proem” which is a poem about poetry. It articulates the several changing relationships between the poet and his audience from the composition of the poem to the reading of it by the audience and their response to it. There are also complex relationships between the poet and the poem – his own poem at the time of creation and after the writing and release of it. It begins with “Not in the saying of you are you said” and ends with “you are always about to be yourself in something else ever with me”.

There are infinitely interesting insights into the way a poet’s mind works in that sometimes-elusive poem. But the way Carter’s mind works evokes even more intrigue. The difference between the straightforward and the infinitely complex again comes out when he explained differences in language use by normal speakers or by persons playing crossword puzzles. “They approach words and go so,” he said indicating a straight, forward movement. “But I approach words and go so,” gesturing with his palm to indicate a crooked turn away from the straight path.

Carter, therefore had very special relationships with his audience which help in his importance as a Guyanese poet, and even in the continuing definition of national poet, and these also help to show why he is so important to the poetry and nation. A closer examination of ‘The Poems Man’ may illustrate this. The poet described a girl “no more than 12”, standing on the bridge outside her home as he was passing on the road. “Look, the poems man,” she called out, and the poet considered it a very significant encounter.

It exhibited Carter as a poet of the people. The little girl recognized him, and she recognized him as a poet. This is a rare close encounter between a poet and village or community people, who are not normally regarded as having any interest in poets and poetry. But Carter’s immense national popularity is another factor of his greatness and his special place in the literature. The girl recognized him as a celebrity and showed some excitement at his appearance in such proximity to her and her home – she called out to her mother to behold his presence.

Furthermore, “poems man” is a Creole construct for the English word “poet” (which might not have existed in her vocabulary). Carter was known for his proletarian disposition in his approach, generally, and considered the encounter important. Creole constructs, influence and syntax were known to be employed many times in the English of Carter’s poetry, although he was not known to have any entirely creole poems. We find examples in: “Is the university of hunger, the long march”; “Is they who have no voice”, inter alia. So that the poet bridged many gaps in this poem – generation, as he remarked at her being “no more than twelve, and I the man she called out at”; and continuity, as they met, significantly, on a bridge and he narrated “she going her way, I coming from mine”; class and consciousness as was clearly enunciated in her creole language. There was a sense of honour felt by the poet, and he bore the title of poems man with some proud acknowledgement.

It matters also that Carter is very quotable. His language inspired and so many lines are profoundly memorable and meaningful. Other writers have used them as titles of their works such as poet and novelist Grace Nichols who took Whole of A Morning Sky as the title of her novel set in the racial riots from “Black Friday 1962” in which the morning sky turned crimson from the many fires set. Rupert Roopnaraine titled his collection of essays The Sky’s Wild Noise from Carter’s tribute to Walter Rodney. Gordon Rohlehr has borrowed more than once – he titles a critical paper “A Carrion Time” and a book of criticisms is called My Strangled City.

From the Poems of Resistance through his other books Poems of Succession and Poems of Affinity with the many published groups in between to the many other editions of selected poems that came out in the early part of the present century, Carter was the main definer of Guyanese poetry. He was very instrumental in giving it shape and international prominence for several years before and after independence. The meaning of national poet thus assumed many dimensions and Carter fit them all.