We noted last week that the budget provides a glimpse that the government is starting to think about a coherent development strategy. The column furthermore underscored the need for greater clarity of the principles underpinning the vague development programme. For example, the budget speech presents better governance and better government as parallel to the Green State Development Strategy (GSDS). It is unlikely that in a divided country the quality of governance and governance can be separated from any economic development programme.

We noted last week that the budget provides a glimpse that the government is starting to think about a coherent development strategy. The column furthermore underscored the need for greater clarity of the principles underpinning the vague development programme. For example, the budget speech presents better governance and better government as parallel to the Green State Development Strategy (GSDS). It is unlikely that in a divided country the quality of governance and governance can be separated from any economic development programme.

While many observers are preoccupied with the more tangible measures of the budget like housing, roads, bridges, schools, etc, I prefer to focus on the intangible infrastructure of governance, government and social cohesion. This intangible infrastructure is not evident on a daily basis as a new bridge across the Demerara River would be, but it is crucial for the present and after 2020 when the State will assume a greater role in the economy; a role in which government will receive oil rents and will have to decide how and when to spend these funds. Circumventing the resource curse and probable open civil conflict after 2020 will depend largely on the quality of government and whether it is perceived to be fair in its allocations.

The budget speech said some of the right things, but it has not followed through with action in some areas. For instance, there is no financial allocation to constitutional reform even though this is listed as an instrument of better governance. I could not find in the budget estimates funds appropriated for constitutional reform. The estimates indicate that monies have been allocated to social cohesion which comes under the Ministry of Presidency. Labour costs associated with social cohesion amount to $186.2 million while other charges are budgeted to be $203.9 million. It would be interesting to find out what are these other charges.

To further put things into perspective, the employment cost of citizen and immigration services under the Ministry of Presidency amounts to $238 million, while other charges are budgeted to be $337 million. What might these other charges be? How many foreigners have become Guyanese citizens in recent years? The general pattern arising is the government talks and writes in the budget speech about constitutional reform, but it does not act. As an aside, I prefer to use the term constitutional overhaul because the present one is not helpful for a country like Guyana. A completely new one is necessary for post-2020 Guyana.

The public must start from the assumption, given present institutional and constitutional shortcomings, government is going to pursue the short-term self interest of those in power and the immediate interest of the ruling political party over the long-term interests of the country. This is what we call in economics the time inconsistency problem in which the public knows the government has an inherent tendency to pursue narrow and short-term interests. Therefore, the responsibility is on the government of the day to make a credible commitment that it is serious about addressing the structural and institutional deficiency in Guyana. A credible commitment by the government is the only way to break the time inconsistency problem and motivate the private sector and individuals to change their expectations and their risk premium. Credible commitments are not one-shot measures, but are signalled continually.

Recent actions only serve to reinforce the public’s belief that the government is up to no good. The administration lied to the public about receiving US$18 million from ExxonMobil. The government was eventually forced to notify the people that it did receive the money which was supposedly placed in an escrow account that would be used to pay legal fees. National security was invoked by the President vis-à-vis Venezuela. However, this is not a credible explanation for at least two reasons.

Firstly, ExxonMobil is firmly on the side of Guyana, at least for now. Earlier this year the Washington Post reported that Guyanese oil exploration and proposed extraction are not only about economics but also a means of getting back at the socialist Venezuelan government for nationalizing ExxonMobil’s assets over there. There is no way Venezuela’s military could bully ExxonMobil or Guyana over the oil asset right now. This scenario could eventually change if the Venezuelan right wing gets back in power, which is highly unlikely to occur in the near future. We do not know for certain how ExxonMobil would react should the right wing regain power in Venezuela. Therefore, it is even more urgent to spend these expected oil revenues most prudently so that Guyana can achieve some economic clout before the geopolitics change.

Secondly, notifying the public of the signing ‘bonus’ does not mean the government had to tell the world it intends to spend the money on legal fees. Money is fungible, therefore depositing the bonus into the Consolidated Fund, which is the legally required course, frees up other funds for paying legal fees when the time arises. As a rebuttal, Minister Jordan argued the PPP did not deposit the US$10 million it received from CGX Energy into the Consolidated Fund. That’s not a surprise since the Jagdeoian PPP is not normally uplifted as the benchmark of good governance and government.

Speaking about the Consolidated Fund, a decision was taken somewhere at the Ministry of Finance to stop reporting the projected and actual outcomes of the Fund. The Consolidated Fund has been a standard part of the budget estimates. This account tells an important story and it is surprising the ministry chooses to stop reporting the two tables showing capital and current accounts. At a minimum a rationale should be given to the Guyanese people why it is not necessary to report this account any more. The account has been running in the negative, and widening, for at least five recent years, thus the account at the Bank of Guyana is in overdraft. It would be interesting to explore the factors driving the sustained overdraft. The short answer is Guyanese governments, over a long period, are spending more than they are taking in as revenues. It indicates, furthermore, that the governments have been using short-term debt financing via Treasury bills to finance the revenue shortfall. We would explore this issue in a later column given its interesting monetary policy implications.

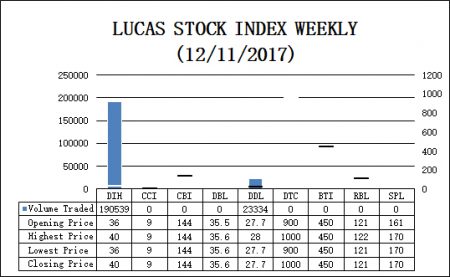

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) rose 2.45 percent during the second period of trading in December 2017. The stocks of two companies were traded with 213,873 shares changing hands. There was one Climber and no Tumbler. The stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) rose 11.11 percent on the sale of 190,539 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of the Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) remained unchanged on the sale of 23,334 shares.

This raises the issue about whether the Minister of Finance is serious about all the good words he made in the 2017 and 2018 budgets regarding the importance of data. If the Ministry of Finance does not believe the public has a right to know about the closing balance in the Consolidated Fund, why should we trust the government is serious about providing statistics such as the unemployment rate or measures of poverty and deprivation? In other words, the decision to stop reporting the numbers of the Consolidated Fund shows a lack of credible commitment to the long-term goal of data availability, a clear perpetuation of the time inconsistency problem.

Perhaps the main problem of bad government and governance is its impact on business investments. Without strong institutions, investors will have to price in a high risk premium in investment decisions. Therefore, Guyana will continue to attract mainly investors in resource extraction, which have very little technological spill over to the wider economy. The manufacturers, industrial farmers and high-value service providers will continue to stay away.

Comments: [email protected]