By Frank BirbalSingh

Frank Birbalsingh is Professor Emeritus of English, York University.

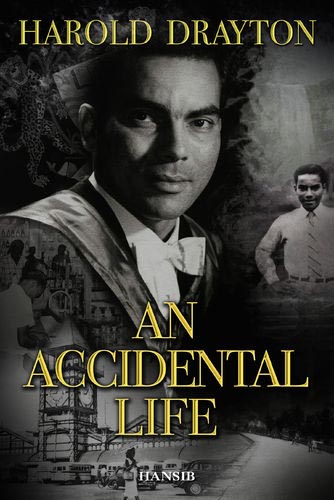

Harold Drayton’s extensive memoir An Accidental Life, published by Hansib Publications Ltd. (it comes in at 911 pages), luxuriates in rich detail from his career within a uniquely Caribbean context, specifically British Guiana, which assumed the name “Guyana” after Independence in 1966. What is unique about B, G, and other Caribbean colonies is the forced employment mainly of African slaves and Indian indentured immigrants, and social values of race, colour and class that persisted even after Independence. These values seemed like those of South African apartheid except that they were not legally enforced, but simply sanctioned by habits that, over centuries, produced a social structure with a tiny group of Europeans or Whites at the richest level, another small group of coloured or Browns (mixed Blacks and Whites) at an intermediate, middle class, and a majority of the population – descendants of Africans or Indians – at the lowest, poorest level.

Harold Drayton’s extensive memoir An Accidental Life, published by Hansib Publications Ltd. (it comes in at 911 pages), luxuriates in rich detail from his career within a uniquely Caribbean context, specifically British Guiana, which assumed the name “Guyana” after Independence in 1966. What is unique about B, G, and other Caribbean colonies is the forced employment mainly of African slaves and Indian indentured immigrants, and social values of race, colour and class that persisted even after Independence. These values seemed like those of South African apartheid except that they were not legally enforced, but simply sanctioned by habits that, over centuries, produced a social structure with a tiny group of Europeans or Whites at the richest level, another small group of coloured or Browns (mixed Blacks and Whites) at an intermediate, middle class, and a majority of the population – descendants of Africans or Indians – at the lowest, poorest level.

Alexander (Alec) Drayton, Harry’s father, came from a “coloured” or brown family of mixed European/African descent, living in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital city. Alec courted a Portuguese woman, Agnes Da Camara who became pregnant; but he could not marry her because he already had a wife, and Harry was born out of wedlock in 1929. Agnes then married George Alfred Butts, an Indian-Guyanese whose name conceals his Indian-Guyanese identity. Unusual too, despite acknowledgement of financial aid from Alec during his studies, is Harry’s portrait of Alec as one merely of studied exactness or deference, while that of his stepfather, addressed throughout An Accidental Life, simply as “D,” exudes ample and warm affection, undisguised admiration, even reverence. By admitting: “whatever I [Harry] have been able to achieve in this life, I owe to him” – D., Harry suggests that sometimes water may be even thicker than blood.

Apart from brilliant sketches of people like D, An Accidental Life consists of diligent, and relentlessly researched documentation of the author’s career, from his early education in Georgetown to a brief, teaching stint in Grenada; abortive studies at the University College of the West Indies, (UCWI) in Jamaica; another brief stint of teaching in Jamaica; zoological studies and graduation with a Ph.D. from the University of Edinburgh; yet another brief teaching stint, this time in Ghana; establishment of the University of Guyana; and working with the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), and the World Health Organisation( WHO) University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, University of Texas. Although this list confirms Drayton’s professional distinction, including outstanding services to public health policy, it does not perhaps fully proclaim the progressive, revolutionary, socialist ideology that inspired, for instance, his attendance at student festivals in Eastern European countries, and his seminal contribution to establishment of the University of Guyana, the centre-piece of his achievement as a whole.

After first attending St. Theresa’s Private School in Georgetown, Drayton moved to Modern High School, where he encountered anti-colonial ideas already circulating in his own home, either directly from D or through evening discussions with family friends, for example, about topics such as the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and increasing agitation in India for Independence from British rule. In his classes, too, one teacher M.M. Beramsingh denounced the conventional, textbook view of Robert Clive as an heroic British icon who triumphed over Indian forces of the Nawab of Bengal. Instead, Beramsingh claimed that Clive was “a brigand who had ‘won’ the 1757 battle of Plassey only because he had bribed the Nawab’s soldiers.”

After first attending St. Theresa’s Private School in Georgetown, Drayton moved to Modern High School, where he encountered anti-colonial ideas already circulating in his own home, either directly from D or through evening discussions with family friends, for example, about topics such as the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and increasing agitation in India for Independence from British rule. In his classes, too, one teacher M.M. Beramsingh denounced the conventional, textbook view of Robert Clive as an heroic British icon who triumphed over Indian forces of the Nawab of Bengal. Instead, Beramsingh claimed that Clive was “a brigand who had ‘won’ the 1757 battle of Plassey only because he had bribed the Nawab’s soldiers.”

In 1946, Drayton moved to Queen’s College, (QC) the prestigious government school for boys in which elements of racist/colonial attitudes still survived. For example, although he had won the Guiana Scholarship, in 1926, and acquired teaching qualifications at Cambridge University in England, a black Guyanese Norman Cameron was at first refused a teaching job at QC, his old school; and when students of the QC Literary and Debating Society invited a speaker, Jocelyn Hubbard, from a socialist group – the Public Affairs Committee (PAC), precursor of the People’s Progressive Party formed in 1950 – British Headmaster Captain Nobbs accused the students who invited Hubbard of “gross ingratitude” for ignoring the educational assistance they had received from Britain and: “associating with elements and ideas subversive to the [British] Crown.” Such attitudes were evidently encouraged by The Atlantic Charter which was signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, in 1941, declaring self-determination for all nations, and provoking no doubt unforeseen ideological division in the battle for decolonisation that inevitably followed, not only in B.G. or the Caribbean, but worldwide.

Yet, since it crosses authentic literary genres from history and politics to autobiography and

memoir, An Accidental Life should not be considered simply either as a political treatise or

voluminous memorabilia: its compulsive documentation also includes dramatic episodes,

penetrating, psychological studies, and enduring relationships with trusted friends such as

Guyanese Josh Ramsammy, and Jamaicans Neville Dawes and Richard Hart who, mysteriously,

it seems, re-appear at strategic locations, in widely separated parts of the world. Nor should we

forget that Drayton first married a Trinidadian, Kathleen McCracken with whom he had two

children, between 1954 to 1982, a second wife Maureen Montplaisir, from St. Lucia who died in

1995, and, in 1997, his current wife, Vonna Lou Caleb, a Guyanese.

Indeed, the extraordinary saga of Drayton’s expulsion from the University College of the West

Indies in Jamaica, in 1951, after spending one night off campus with then fellow student

Kathleen, and, more importantly, his absorbingly titanic but vain struggle for reinstatement at

UCWI afterwards, is the most dramatic episode in his entire book. But if all these varied

incidents, episodes or relationships are accidents, imagine how much more accidental are

Drayton’s most formative influences – character building from D, an Indian-Guyanese, and

political example from Cheddi Jagan, another Indian-Guyanese – for someone of his Caribbean

Amerindian ancestry, in Georgetown, an overwhelmingly African-Guyanese city, in the 1930s

and 40s!