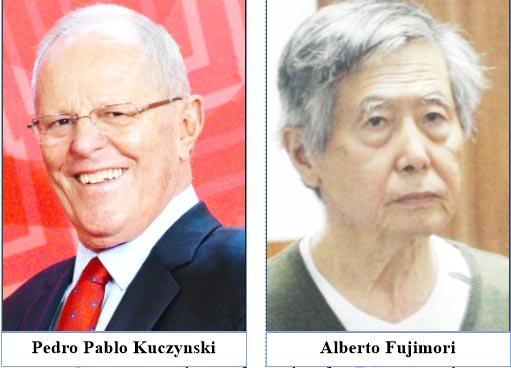

LIMA, (Reuters) – Last week, as Peru’s President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski scrambled to survive a bid in Congress to oust him in the wake of a graft scandal, his jailed authoritarian predecessor Alberto Fujimori called on his loyalists in Congress to save the head-of-state.

The day before the vote and during hours of debating, Fujimori received prison visits or spoke on the phone with at least seven of the 10 lawmakers who broke party ranks to keep Kuczynski in office, according to prison records and interviews with two of the lawmakers this week.

Legislator Maritza Garcia said it was Fujimori’s gentle warning that toppling the president would destabilize the economy that cemented her decision. Bienvenido Ramirez said Fujimori encouraged him to cast a vote of conscience.

“He told us to trust our hearts … that the country hung in the balance,” Ramirez told Reuters.

Kuczynski ended up surviving the vote with the help of the 10-strong rebel faction, led by Fujimori’s 37-year-old lawmaker son Kenji. Three days later, Kuczynski pardoned Fujimori.

Kuczynski’s decision sparked unrest, resignations, and prolonged the biggest political crisis this century in Peru, a top metals exporter that has enjoyed a fast-growing economy, relative stability and significant strides in development in recent years.

The power that Fujimori wielded from his prison cell – just days before being rushed to the hospital on the eve of the pardon – could be pivotal to Kuczynski as he seeks to rebuild his government.

“We’re going to follow the guidance of ex-president Fujimori. He’s experienced and has profound knowledge of the political world,” Garcia said, calling Fujimori her party’s “maximum leader.”

Fujimori’s son Kenji has courted ties with Kuczynski’s government as he has challenged his sister Keiko’s leadership of the rightwing opposition party that controls Congress. The two siblings are widely seen as potential president contenders in 2021.

Kuczynski expects the group of 10 rebel lawmakers, led by Kenji, to grow to about 30 under Fujimori’s influence now that he is a free man – splitting Keiko’s bloc in half, a government source who asked not to be named told Reuters.

The new bloc in the 130-member Congress could help center-right technocrat Kuczynski, a former Wall Street investor, govern for the rest of his term, after a tumultuous 17 first months in office that were marked by clashes with Keiko’s supporters.

Already, support for him has rebounded. In an Ipsos poll published in local daily El Comercio on Saturday, Kuczynski’s approval rating rose 7 points from two weeks ago to 25 percent, even as 63 percent saw the pardon as the result of a political deal to save his own skin.

It was unclear if Fujimori’s lifeline to Kuczynski might evolve into a full-fledged alliance between the two 79-year-olds.

Garcia and Ramirez deny their votes were part of a quid pro quo, and surrogates for Kuczynski and Fujimori have repeatedly defended the pardon as justified on medical and humanitarian grounds.

“This was the exclusive decision of the president. At no point was it about a deal with Kenji or Alberto Fujimori,” Kuczynski’s office said.

Prime Minister Mercedes Araoz stressed that Kuczynski had openly talked for months about evaluating a humanitarian pardon for Fujimori, and finally took the decision on Christmas Eve after Fujimori was hospitalized for what his doctor described as life-threatening blood pressure and heart problems.

‘POLITICAL PARDON’

But Fujimori’s opponents – who, since the pardon, are now also Kuczynski’s opponents – said Kuczynski walked into a trap.

“Our president just gave himself away to the biggest mafia in Peru’s history,” said Marisa Glave, one of several leftist lawmakers calling for Kuczynski to resign. “He’s now Fujimori’s hostage.”

Fujimori, who remained in hospital in stable condition on Saturday, governed Peru with an iron fist from 1990-2000.

While many consider him a corrupt and ruthless dictator, others credit Fujimori with pulling Peru from economic ruin and quashing a leftist insurgency. The Ipsos poll showed 56 percent of Peruvians favor the pardon.

Kuczynski’s decision, which cleared Fujimori’s convictions for graft and human rights crimes less than halfway through his 25-year prison sentence, has been slammed by human rights advocates as an insult to Fujimori’s victims and a blow to the global fight against impunity.

Some activists and lawyers say the process via which Kuczynski granted the pardon was secretive, riddled with irregularities and could be revoked by courts.

“A humanitarian pardon isn’t an absolute right of the president. It must be reasoned logically and can’t violate fundamental rights,” said Jo-Marie Burt, a political scientist at George Mason University and senior fellow at human rights group the Washington Office on Latin America.

Pardons have been revoked in Peru before.

A television tycoon convicted of taking bribes from Fujimori’s spy chief was pardoned in 2009 after claiming to be gravely ill. But he was sent back to prison a year later after being found out and about in town and in good health.

The pardon for Fujimori was approved in 13 days, after Kuczynski received a recommendation from a three-member medical board that included one of Fujimori’s personal physicians.

Experts said the process was unusually fast and lacking in transparency.

“No humanitarian pardon, even for those requested by prisoners suffering terminal illnesses, start and finish so quickly,” said Roger Rodriguez, the former head of the pardons commission who quit his most recent ministerial post as human rights director in protest.

“This was no humanitarian pardon. It was a political pardon,” said Rodriguez. “There are elements here to challenge its validity in court.”