![]() “All the Money in the World,” the recent Ridley Scott drama, is perhaps the darkest film I’ve seen from 2017. I don’t mean this in the sense of tone or theme. I mean this visually. Lighting, costume and production design wise, this is an incredibly dark film and I’ve been thinking about how that darkness feeds into the work itself.

“All the Money in the World,” the recent Ridley Scott drama, is perhaps the darkest film I’ve seen from 2017. I don’t mean this in the sense of tone or theme. I mean this visually. Lighting, costume and production design wise, this is an incredibly dark film and I’ve been thinking about how that darkness feeds into the work itself.

Of course, before one even examines a frame of the dark world on display here, one must address the elephant in the room, which threatens to overshadow “All the Money the World.” This film, I suspect, will be remembered for its behind-the-scenes drama more than what came out of it. Towards the end of last year, when multiple allegations of sexual misconduct were made against Kevin Spacey, director Scott decided that despite having finished shooting and editing the film, it must be recast to prevent the actor’s name from besmirching the film’s reputation.

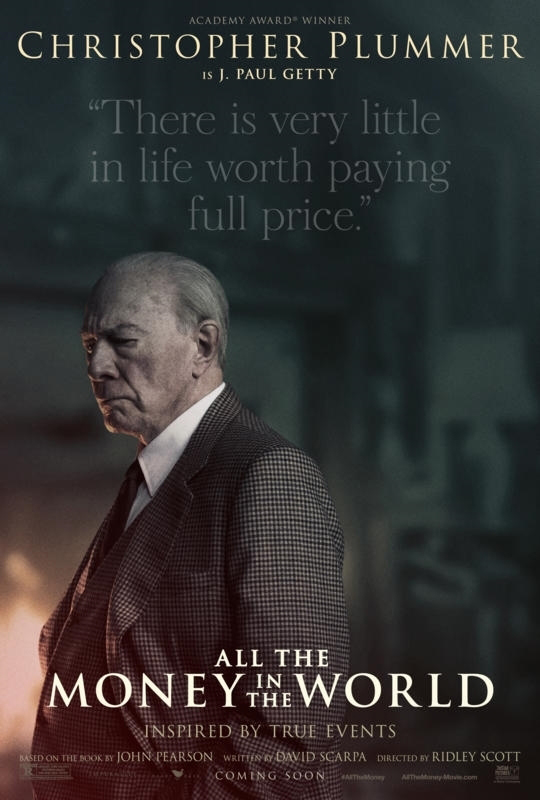

And so, Christopher Plummer was hired to take over the J. Paul Getty role originally played by Spacey and reshoot all the scenes with the film’s two other main cast members, Michelle Williams (first billed) and Mark Wahlberg, in 10 days. This is, already, a big enough controversy, and unparalleled in modern commercial films. The behind the scenes drama intensified this week when it was revealed that despite the same agents, Wahlberg had managed to negotiate a $US1.5 million increase for the reshoots, unbeknownst to the cast and director. Williams, because she appreciated what Scott was doing with the reshoots, agreed to do it for free (or the lowest salary allowed for unionised actors, US$80 a day). A single controversy is huge, while two of this size are eclipsing. And from that fraught backstory, where does that leave the film?

Scott, forever an erratic director, has on the surface created a film that fits his typical oeuvre. This dark and moody period piece, a crime drama with masculine figures, is very much in line with his most common thematic concerns. The film is based on a book chronicling the true story of the kidnapping of young John Paul Getty III in Rome. The kidnappers are hoping for a quick and easy ransom from J. Paul Getty Sr., the richest man in the world. But, as young John Paul tells us in the opening, his grandfather is not just the richest man in the world but the richest in history. And he is not a regular person, and so what seems like a simple case of ‘demand ransom and get paid’ turns into something more.

Scott, forever an erratic director, has on the surface created a film that fits his typical oeuvre. This dark and moody period piece, a crime drama with masculine figures, is very much in line with his most common thematic concerns. The film is based on a book chronicling the true story of the kidnapping of young John Paul Getty III in Rome. The kidnappers are hoping for a quick and easy ransom from J. Paul Getty Sr., the richest man in the world. But, as young John Paul tells us in the opening, his grandfather is not just the richest man in the world but the richest in history. And he is not a regular person, and so what seems like a simple case of ‘demand ransom and get paid’ turns into something more.

The central story is interesting if not particularly compelling because so much of it is public knowledge. J. Paul Getty is an irascible and distant man albeit refracted through a dark humour that is at times perverse. Plummer does well with this sort of role. The film is, at times, too enamoured with him and its first half an hour suffers the most from this, beginning with a disjointed bit of time hopping that feels too perfunctory at first, with title-cards showing places and years and months too quickly to be followed and too hazily to care for. And then, about 20 minutes, maybe half an hour into the film, it improves decidedly. Williams, as the mother of John Paul Getty III (and wife of John Paul Getty II), is given more to do, and she immediately takes the film into her grasp.

There is one thing that disconcerts me about the recasting of Spacey. Because of the nature of the recasting, it has placed a lot of attention on Plummer for his (admittedly) good work with little preparation. But that focus has taken attention away from the real acting talent at the centre, Williams. Her performance is a marvel to watch. Gail is not just a symbol of the 99% working against the 1%. In fact, her characterisation is sometimes as distancing and baffling as those she’s fighting against. She is a mother in distress, but also sardonic, distempered and prickly. It’s a marvellous performance. Her vocal cadence, the way she walks, the way she holds her body still before and after key catastrophic moments – it’s an excellent embodying of a character that could have been so staid. While Plummer’s performance is like hard liquor, immediately affecting for its harsh and visceral quality, Williams’ is more like a strong champagne. At face value, it seems too florid for effectiveness; it beguiles you with its delivery and like a heavy mist it completely envelopes you. Scott knows what he’s doing when he ends the film on a 30-second shot of her face.

Of the trio at the film’s centre, Wahlberg is serviceable but hardly makes an impression. It makes the controversy of his payment even more bizarre if fittingly ironic for the bent Hollywood world. He is never bad, but never makes an impression in a role that seems ripe for recasting (perhaps Edgar Ramirez, Leonardo DiCaprio or Oscar Isaac, the possibilities are endless). Despite fair work from Charlie Plummer (no relation to Christopher), young Paul isn’t given much to do, so the film is less about John Paul Getty III, than the people around him.

So, let’s return to that darkness. Visually, Scott and cinematographer Dariusz Wolski, working on their sixth film together, are doing what, at first, comes across as the director’s prerequisite dark and moody atmospheric shoots. It works mostly, but sometimes it does not. And when it does not work, it’s not pretty to look at. The film looks dull at first glance. There’s a scene where Getty walks in his yard that seems like it’s from a black and white movie but for a burgundy scarf. The dun dullness of it works in some areas, though, especially when the music (Daniel Pemberton’s score is not particularly original but it’s excellent) augments its off-kilter nature. Dark photography as a metaphor for dark lives is not ingenious and at times it’s too expected to be effective. Of the technical aspects, the real winners here are Janty Yates’ costume design (another Scott partner) and Arthur Max’s production design. Money in the world of the film does not enliven, it congeals. We can see it in the luminous Getty mansion. We can see it in the squalid camp Paul is being kept in. The effect is discomfiting. They distil the myth of darkness in a way that works.

So what do we have left when “All the Money in the World” has spent itself? Beyond historic recasting and the offensive pay disparity, we have a solid film with an excellent central female performance. “All the Money in the World” never does reach the psychological aspirations it hopes to. It’s a common thread in Scott’s films, which tend to be more interested in the surface. The film allows us a gaze into the lives of the petty rich. Through a well moneyed glass darkly, there is no great depth of anything to examine underneath, though. Only images of pretty things and cold people. And a woman fighting for her son’s life.

“All the Money in the World” is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas.