By Deo Persaud

Born in Guyana, Deo Persaud grew up in Georgetown. He was educated in the UK, and has lived and worked there for the last fifty years. Part of his work while living there was documentary photography specializing in cultural and social images. Having an interest in sugar and its decline globally and in particular in Guyana, it was through photography that he sought to expose the inability and incompetence of successive governments when it came to alleviating the brutal system of the industry in Guyana.

One day I was with Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine, travelling on the East Coast. We were at a junction in Enmore and nearby was a truck laden with men, covered in mud, wearing ragged clothes. This was in 2004 and the killing spree was wreaking havoc on the coast. Tensions were running high. I glanced over at the truck, not looking closely, and casually asked, “So dem ketch nuff criminals, Rupert?” He looked at me and shook his head. “What is the matter with you, Deo? These are cane cutters.”

One day I was with Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine, travelling on the East Coast. We were at a junction in Enmore and nearby was a truck laden with men, covered in mud, wearing ragged clothes. This was in 2004 and the killing spree was wreaking havoc on the coast. Tensions were running high. I glanced over at the truck, not looking closely, and casually asked, “So dem ketch nuff criminals, Rupert?” He looked at me and shook his head. “What is the matter with you, Deo? These are cane cutters.”

How much we do not know. How easy it is to close our eyes to the activity around us. There and then, I decided that I would use my camera to help make this labour visible, and to offer a visual document of a day in the life of sugar workers on Guyana’s coast. In 2004 I received permission from GUYSUCO to go into the canefields at LBI estate. Women work as weeders in the fields, and African men are more present as canecutters in other estates, but I accompanied a truckload of mainly Indian men. This, then, is just one of the many stories that could be told. I offer these reflections on that journey taken fourteen years ago.

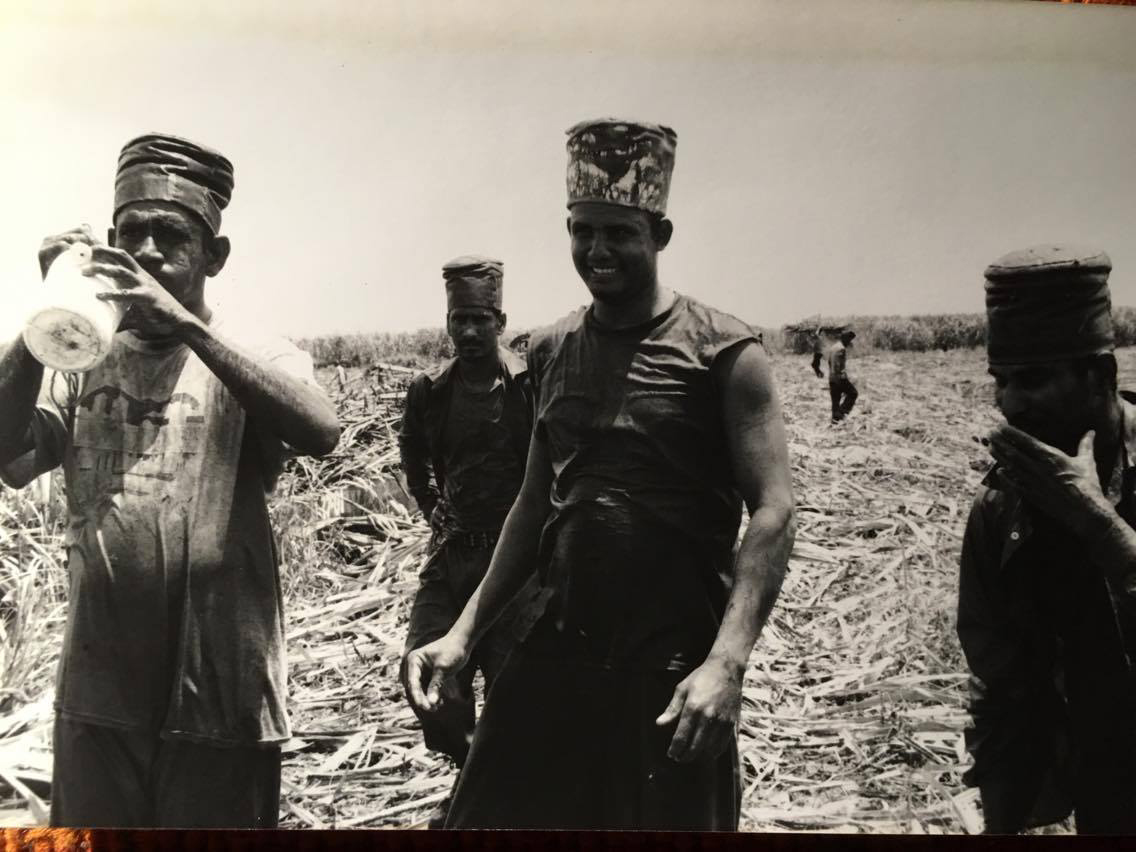

“Is two ahwee wuk fuh GUYSUCO. Me and meh wife. She ah get up dayclean tuh cook fuh me. Roti, curry, dhall an rice. Wen you go ah field dey ent gat shop to go an buy food. Yuh haffa eat wha’ yuh wife cook.” This is what he told me as we waited for the GUYSUCO truck which would take us to the backdam of LBI estate. It was six in the morning as we stood on the main road awaiting the arrival of the truck. The cool morning breeze and the awakening of an agricultural Guyana beckoned my inquisitive mind. I looked at the gathering of the fifteen souls at the truck stop waiting to be taken to a brutal world of cane harvesting in Guyana. All men, most were of Indian descent, dressed in clean ragged clothes. They could have easily fitted into the state of Bihar. Cutlasses, plastic bottles of rain water and the ubiquitous rucksack stuffed with ‘wuk clothes’, food carriers laden with their meals for the day. In the sack was the ‘takka,’ a kind of top hat that is worn to buffer the weight of the cut sugar cane while laden on the head. Inside the ‘takka’ were bits of old cloth, curtains, old clothes. Then there were the GUYSUCO shoes. These were given out free to each seasoned harvester. “After two wear, dem done,” he told me.

We were the last to be picked up, and helpful hands reached for me as I clambered onto the already packed truck. The track that led to the canefields was muddy, badly maintained, bridges that spanned crisscrossing canals and vast fields of sugar cane swaying in the cool Demerara horizon. The human cargo was discharged at various points, depending on what fields were going to be harvested. A gentleman wearing better clothes and carrying books went around calling and ticking off names on his clipboard as he moved around the assembled group. Sometimes there were anxious faces. I was later told that there was a favouritism that existed and if the ‘foreman’ did not like you, you did not get any work for the day or were given some lesser operation where the pay was not so good. From the assembled group of about 75, about 15 or so were men of African descent. In general the younger men tended to stick together, while the older ones mixed more freely with everyone across generation and race.

The working groups divided into gangs and these also subdivided into a group of four or sometimes two who were given their specific target. The land, the canals, and the unrelenting mud were serious considerations. From the dam you had to get across a canal and this was bridged by a plank of wood measuring ten inches across and about twenty feet in length. The cane cutters had to fetch this monster wherever it was required. Heading into the canefield held its own terror. You are faced with a wall of sugar cane and you literally have to machete your way in, slicing the obtrusive sugar cane and solid vines that entangled the rising shoots. “You hit that vine and yuh cutlass bounce back, is buss yuh head gun buss,” he told me as he carved his way into the fields, me following the path he cut. The gruesome task began. Men cut, they swiped, precise moves, strong hands grasping. Grunts. Sweat. A certain amount has to be left for the next crop and the cutting of the cane had to be done at a precise angle. Bundles of cut cane were left on the ground to be transported to the waiting punts later. Each bundle averaged about eighty pounds, to be self-loaded, perched on the takka on one’s head and taken to be dumped into the punts.

The men, especially the Indians, smoked a lot. After a certain section was done, a momentary break from the seemingly unending toil was a well earned pull on a Bristol cigarette. Cigarettes were a premium in the backdam, and friendships are formed with the sharing of a drag after a toil in the rising mid-morning sun.

Like cigarettes, water was very important. Some men came into the backdam without the resources of fresh water. They had to rely on their friends, for the simple reason that they had no potable water at their place of abode. Others got water from the rainfall which they harvested from their roofs. Lunch break came around 11:30. Individuals, pairs, or small groups sat around on cut bundles of cane. Africans brought bread and stew. Roti, curry, rice and dhall were the main staples for the Indians. There was sharing and camaraderie. I sat on a cut bundle of cane, observing the operation unfolding before me. A man warned me, “Uncle, be careful how yuh sitting. Scorpion or snake could be hiding inside dat bundle”.

Back to work. Massive acreage was now cut and it was time to load the punts. The bundles of cane were strapped using dried cane leaves. To strap the bundles of cane together, some of which weighed one hundred pounds, required brute strength. A loose strap meant less income if the bundle broke loose on the way, scattering the cane in all directions. I watched these men grappling their burdensome bundles, fixing them on their heads and then with determined precision heading for the empty punts, waiting to be loaded with the day’s toil. I was told that a ‘good man’ can fetch three tons of sugar cane laden on his head in one day. For this, I was told at the time (2004), he can earn about three thousand Guyana dollars or the equivalent of roughly fifteen US dollars. But getting the right pay for the weight that was cut and loaded is not straightforward, historically and in the present – the foreman and checker undercounting or overpaying workers depending on who is out of favour or who is a friend or kindred spirit. I was also told of a very insidious operation called sweet water. Sweet water is a term used to describe the dumping of cane juice into the canals. The reason I was given was that to avoid bonus payments for the amount of cane cut and delivered to the factories, cane juice volumes were dumped in order to show that the required amount for the payment of a bonus was not reached. In the factories where disputes occurred, sabotage to the machines was a common practice when cane cutters felt they had been cheated.

I observed the toil, the sweat, the sticky cane juice running down the faces and bodies of these determined men who are well versed in the brutal work of sugar cane harvesting in Guyana. Physical injuries are common, with a frail social back up for anyone injured in the fields. I found myself thinking as I followed the men in the cane fields, “there is not much difference between what I saw today and what one reads about the nature of this work during the days of slavery. And what about the Enmore Five? What about Kowsilla? What did they die for?”

Work over, truckloads of tired men headed to their different villages, mine the last stop of the day. With a small group, we headed to the rum shop, a usual fixture after a day’s work. Stories were told by the men, ambitions for them and their young families were expressed. I was invited to their homes, saw their modest conditions of living, heard about their aspirations and dreams. Running water, electricity, a television, education for their children. “Well Uncle Deo, all ahwee want is a lil house, a nice yard, few pickney and a good wife. Me would like me pickney go school, tek education and come right. Dat is all me want. Me haffi cut cane because me nah tek education. God spare me hope me pickney nah go through dis!”

At least they were not broken – it is the system that is broken. It was under the PPP/C in 2011 that the shutting down of the estate at LBI began, a process that was completed in 2016 under the APNU+AFC administration. Back in 2011, a female sugar worker was interviewed by Kaieteur News. A single mother of six who had been working at LBI for 22 years, she was reported as saying: “Minibus fare gone up, bread gone up, cost of living going up, and we are not getting no increase…these people need to tell us exactly what is going on, one time they telling us that they merging and another time they closing.”

I wonder what happened to the cane cutters at LBI who let me walk into the backdam behind them to capture their day, and all the other workers, men and women, African and Indian, and the families and communities that depend on them? What has become of all of their dreams? Now, with the news of more than four and a half thousand sugar workers laid off, I wonder how much has changed. Sweetening Bitter Sugar is the title of a book by Professor Clem Seecharran. From the time this crop sprouted its first shoots in the soils of Guyana, working peoples have only ever gotten the bitter end of the stick.