Buck Hill, in Wismar, Linden, is a haven for its more than 100 residents—including a large percentage of children.

When I arrived at Buck Hill, children were making their way to afternoon lessons; others were on their way home from school. In a yard where the pink Hibiscus flowers stretched over the fence, a woman was bent over some coconuts, sorting them. On one side, five-year coconuts were kept together in a pile, while the three-year ones were in another. The woman did not give her name but pointed out a steep, bumpy path roughened by rocks and giant tree roots through which three children navigated and clambered their way through to the village at the bottom of the hill. The track, she said, was once one of the busiest roads in Wismar with trucks and cars driving along it all day but then it began to erode and was neglected, resulting in the way it looks today. She wants it fixed so that children can properly access it on their way to or from school.

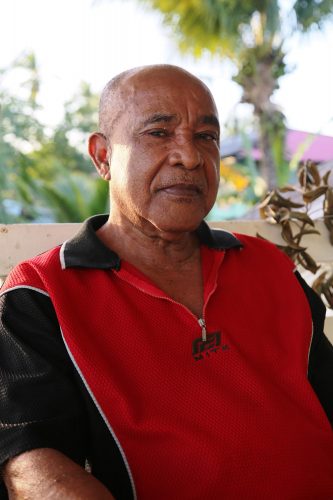

Seventy-year-old Mortimer D’Agrella sat in his hammock checking his watch, timing his bread that was baking in a wood oven nearby. He hails from Drudge Creek, Pomeroon where he built boats with his father and brothers. But the life there, he said, was just about building boats and mostly farming which he deemed boring. Tired of such life and wanting adventure he left to work in the Cuyuni River as a miner, then some years later he settled in Buck Hill. That was 35 years ago.

D’Agrella added that he began working with the Bauxite Mining Company in March 1972 and left on August 18, 1980. Later, he went to the ‘gold bush’ where he worked as a gold miner until four years ago when he retired.

“At the time I moved, mostly Amerindians lived here and only about three African people lived here. It had sheer troolie houses. At that time about forty people lived here, but now Buck Hill has about a hundred or more people. In those days we got water from the spring…. We had pipes but it used to come whenever it feel like and when it come, the water used to run red so everybody prefer to use the spring instead,” he said. The spring has since ceased running and the village now has access to not just clean, potable water, but electricity and the internet as well.

The track the woman pointed out earlier runs right behind D’Agrella’s residence, separated by a gully. He indicated that it was once a main road in the area and was busy at night, as he recalls having trouble sleeping when he had first arrived.

Buck Hill has become an oasis for D’Agrella where he enjoys the quiet and the company of the people here. While he spoke, his two grandsons were at a cherry tree in the nearby vacant lot, which they keep clean for fear of reptiles. Outside the gate through a sandy track, a granddaughter rode her bike up and down.

Returning to our conversation, D’Agrella said one of our biggest problems was unemployment. He noted that there are far too many persons acquiring degrees with no jobs equivalent to same and many of them are forced to accept lower paying jobs or migrate. “For a country to progress, money has to circulate by having jobs; money is circulating in the bush. Yet today is better than long years ago. In 1966, when Guyana gained independence, a pennyweight of gold was $2.50 and a bottle of beer was $1, but in 1991, a pennyweight was $3,000, while a beer was less than $500, so in a way things work out better now,” he concluded.

Isaac Rodrigues hails from Sand Hills situated in the lower Demerara River. He attended the Carmel Roman Catholic school in the capital. Then, after leaving school, he travelled to what was then Mackenzie looking for a job; this was in the 1960s. However, when he showed up at the Demerara Bauxite Company (Demba) there was no vacancy for an 18-year-old. He was encouraged to enrol in the trade school in Mackenzie and told he would be hired upon completion. According to Rodrigues, he learnt a number of trades and specialized as a millwright. He was supposed to study at the school for five years, but because of unforeseen circumstances, he dropped out after three years. While in school he stayed with relatives in Buck Hill. Demba still hired him after the three years and he gave the company 43 years of unbroken service.

The Chapels, he said, were the first family to have at settled Buck Hill and he believes his relatives, the Charleses arrived second, before other families like the Isaacses, DeClous, Wagnoes and the Aarons. According to Rodrigues, prior to that, it was rumoured, there was an Indian family who lived in another village in the Demerara River and had gone to the area to sell provision. They usually took their children along and on one of those days their son left them to go into the bush at Buck Hill in search of fruit. A while after, someone told them that a jaguar had made off with their son. When they went in search of him, all they found was a trail of blood leading further into the jungle. Rodrigues said in all his years, he has never come across a jaguar in the area.

Reflecting on years ago when the village was mostly populated by Amerindians, Rodrigues said that due to migration and death, many of them sold their homes to the Africans wanting to live in Buck Hill and moved on.

The 76-year-old man stressed that as a pensioner he should not have to be paying for garbage disposal. Originally, the Mayor and Town Council took care of the garbage, but two or three years ago Cevons Waste Management took over the service and now he has to pay. “They stopped collecting without an explanation and instead they go to other areas. Now I got to take my pension money and pay a weekly garbage service and that shouldn’t be. On top of that it got a bridge leading to the Wismar Scheme nearby with bush growing at the corner and the people from the scheme dumping their garbage there and the smell is terrible. The Mayor and City Council ain’t seeing this but they collecting their rates and taxes,” he complained.

At a house filled with sculptures and paintings, in a yard filled with flowers lives Wilfred Martin better known as artist Regon. Regon wasn’t born in Buck Hill, but grew up there playing cricket, hide and seek and cowboys and Indians. He attended St Aiden’s Primary but dropped out of school at 12, because his family was too poor to send him. He knocked around for a bit before he began working as an office assistant at Hamilton’s Sawmill. He eventually left for the ‘bush’, where he worked in timber then gold.

In 1985, he left for the USA, but returned in 2012 to spend his retirement here.

Buck Hill is an Amerindian reservation, Regon said, “I believe that’s why the local government isn’t paying much attention here. Initially just Amerindians lived here in the 1950s, but by the 60s people began intermarrying and other races began moving in. Also, what used to be mostly Amerindians is now 30 percent Indigenous with the remaining being mixed races.”

Asked why he returned to Guyana after living and working abroad for so many years, he said he never wanted to leave in the first place, but left because the economy was good over there. Coming back here, he stated, would allow him to be more laid back, not having to take up a part-time job at his age (he is 70 years old) or paying any huge bills but instead he can plant his flowers, hang with friends and work on his art. The self-taught artist said that there are other retirees who want to return, but because they want to be close to their children and grandchildren, they stay on.

He said the first year took some adjusting to like the cold showers and the mosquitoes. “The water accumulates in septic tanks and mosquitoes breed there. They should move away from spraying the road and spray the septic tanks; the mosquitoes bite day and night. Years ago, it wasn’t like this, you hardly see any mosquitoes,” he said.

He recalls spending Father’s Day with his buddies and in the midst of hanging out with them, some children visited. The idea dawned on him that maybe he should have a Father’s Day party and invite the children; some of whom he knew did not have fathers. It has been like this every year since then 2013 when he had just ten children. Last year’s Father’s Day saw 75 children.

Taking the children into consideration, Martin spoke about the ballfield in front of his house which was recently weeded but was not done properly. He believes the neglect of the field was the reason why persons are encroaching on the field, building houses and setting up businesses. The women’s All Stars Cricket Team of Linden, he said, often uses the field for practice and would often reach the championship, but not win. Martin strongly believes that victory would be possible if the team had better conditions to play under. He is appealing to the local government to step up and put in facilities where the Linden team and the children can feel more accommodated.