With more than eight hours of daily laboratory work, Sophia King describes her life as a research scientist as “long and dreary with pockets of great excitement,” which for most people may be pretty ordinary.

A University of California, Los Angeles student pursuing a Masters in Materials Chemistry, King is anything but ordinary as she is part of the less than 30% of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) researchers in the world who are women.

In fact, according to the 2017 report ‘Cracking the Code: Women and Girls in STEM,” which was published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), only 17 women have won a Nobel Prize in physics, chemistry or medicine since Marie Curie in 1903, compared to 572 men.

The report notes that only 28% of all of the world’s researchers are women and concludes that such huge disparities do not happen by chance.

“Too many girls are held back by discrimination, biases, social norms and expectations that influence the quality of education they receive and the subjects they study,” then UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova wrote in her forward to the report.

Bokova’s sentiments have been echoed by her successor Audrey Azoulay, who along with the Executive Director of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka issued a joint statement in observance of International Day of Women and Girls in Science, which is being celebrated today.

“We need to tackle biased perceptions amongst teachers, employers, peers and parents of the suitability of girls and young women to learn science – or learn at all – to pursue scientific careers or to lead and manage in academic spheres,” the UN officials stressed in their statement, while calling for more “concerted, concrete efforts” to overcome stereotypes and biases, including media representations of scientists and innovators as being mainly men.

Such imagery, they argue, “makes it difficult for girls to believe they can be scientists, explorers or inventors.”

‘Role models’

This is something to which Dara Bobb-Semple, who is pursuing her Doctorate at Stanford University, can relate. She tells Sunday Stabroek that she has never been limited in her goals, but the absence of role models in the field of science made it difficult for her to imagine herself in this field.

“No one told me what I needed to be. They only asked me what I wanted to be. I was told that education was the key to success, even though I didn’t know what that looked like, because I didn’t have many role models,” she explained. The lack of a concrete visual sent Bobb-Semple to the literary representations. “I read a lot. So I learned a lot about the world outside of Guyana and knew there was more out there,” she explained.

Eventually she found her direction in a biography of George Washington Carver. “I’m not sure what exactly it was that I read [in the biography] that triggered that. Along the way, I had forgotten. I became constrained to the age old, doctor-lawyer train of thought and since I enjoyed science, I was going to be a doctor. Going to college really changed my perspective. I realized that with my science degree, there was a plethora of things I could do outside of being a medical doctor. I met graduate students there and discovered this whole world of research that I had never known before…. Ultimately, I also found a lot of role models and people along the way who encouraged me to seek out the opportunities that have led me to where I am now,” she explained.

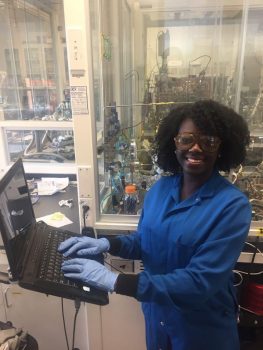

Today, she is part of the prestigious Bent Research Group at Stanford, working in the laboratory of Professor Stacey Bent.

“My job is pretty awesome,” she shares, while noting that she is basically paid to learn, or as she puts it, “soak up knowledge and do cool stuff in a lab.”

In her field, she will eventually become another Guyanese doctor, just not the kind you typically see on TV. Instead, she will be the kind of doctor who helps to build you a more efficient smartphone.

Specifically, her research is focused on “understanding and controlling surface and interfacial chemistry and applying this knowledge to a range of problems in semiconductor processing, micro- and nano-electronics, nanotechnology, and sustainable and renewable energy.”

For the layperson, Bobb-Semple explains that her work helps to make even the smallest electronic components efficient.

“Your smartphone, laptop, computer or even a radio or television are all made up of smaller electronic components, chips and circuits, which have to be made-up. As technology advances, electronics become smaller and smaller, such that your phone allows you to hold a television, radio, computer, GPS in your hand all at the same time. Even with all this, your phone has to have maximum performance with minimum power usage. This is achieved in part by creating new components which are smaller or more complex. These electric components and chips, due the shrinkage and their new 3D structures, have to be made by complicated processes which can result in errors that affect their ability to perform. [Consequently], new techniques must be developed to improve the process of making these components. I work on a technique that can help to alleviate some of the fabrication errors that can occur,” she painstakingly explained.

She describes her relationship with the physical sciences as “a romantic” one. Her great love has always been chemistry even though she struggled with it as a student at Queen’s College.

Today, however, she applies the concepts she has learnt in chemistry and it becomes something tangible.

“I could see, sometimes even touch or smell the results. Research is also a bit like solving puzzles- you have random pieces and you’re trying to see where they fit. I love all these things, but outside of all that, there is also the fact that my research has the ability to impact people’s everyday lives and this is what drives me the most,” Bobb-Semple says.

‘Inspirational’

King’s experiences were a bit different though they both attended Queen’s College, if seven years apart. “I always knew being female and a scientist weren’t mutually exclusive. A good chunk of my science teachers were female and it was inspirational,” she explained. This researcher has instead faced more direct disparagement.

She tells Sunday Stabroek that as a woman in science it’s sometimes exhausting having to prove that she is “just as great as or probably better than others.”

She says that in her experience Bokova’s comment is true, though it is slowly becoming less true with the removal of gatekeepers and the normalization of women in more “alternative” fields. It still remains very easy, though, to consciously or subconsciously, cave under the pressure.

She remembers her experience while applying for her undergrad studies at Adelphi University in Chemistry, when a male family member offered the “sage, unsolicited” advice that she “shouldn’t attempt to be an engineer.”

Today, King is still studying Pure Chemistry rather than Chemical Engineering, but she notes that she studies chemistry with a specialization in materials.

“This was not because of said family member, but because I found Chemistry to be more fascinating, where I’d spend time doing a lot of dirty work, trying to understand the fundamentals of what I’m making, how to optimize it and how it functions,” she explains.

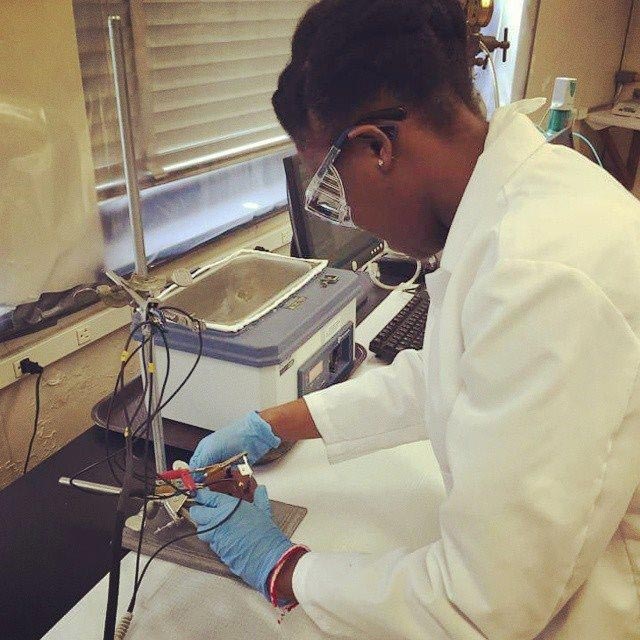

Any given day will find King in her lab at the University of California, Los Angeles attempting to create a film coating for windows that can prevent heat transfer through them.

She explains that if successful her work “could potentially save a lot of energy that is used to replace heat lost through windows during the winter.” The energy saved is estimated to be worth billions of dollars.

For her, “girls should study science because it’s interesting. I get to learn so much about the way the world and things around me works, which I think is great.”