Although we’re well into the second month of 2018, the film world at large is still experiencing arrested development. Until the 90th Academy Award Ceremony in March, many critics are still thinking about 2017 and a few of the major awards players of the season are only now experiencing wide release. Two key players opened recently in Guyana: the police sort-of-comedy “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” and the sort-of-romance “Phantom Thread.” Yes, I am being slightly facetious with the prevarication in the plot descriptions, but only slightly. For both films depend on the core way that neither one is what it seems to be.

Although we’re well into the second month of 2018, the film world at large is still experiencing arrested development. Until the 90th Academy Award Ceremony in March, many critics are still thinking about 2017 and a few of the major awards players of the season are only now experiencing wide release. Two key players opened recently in Guyana: the police sort-of-comedy “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” and the sort-of-romance “Phantom Thread.” Yes, I am being slightly facetious with the prevarication in the plot descriptions, but only slightly. For both films depend on the core way that neither one is what it seems to be.

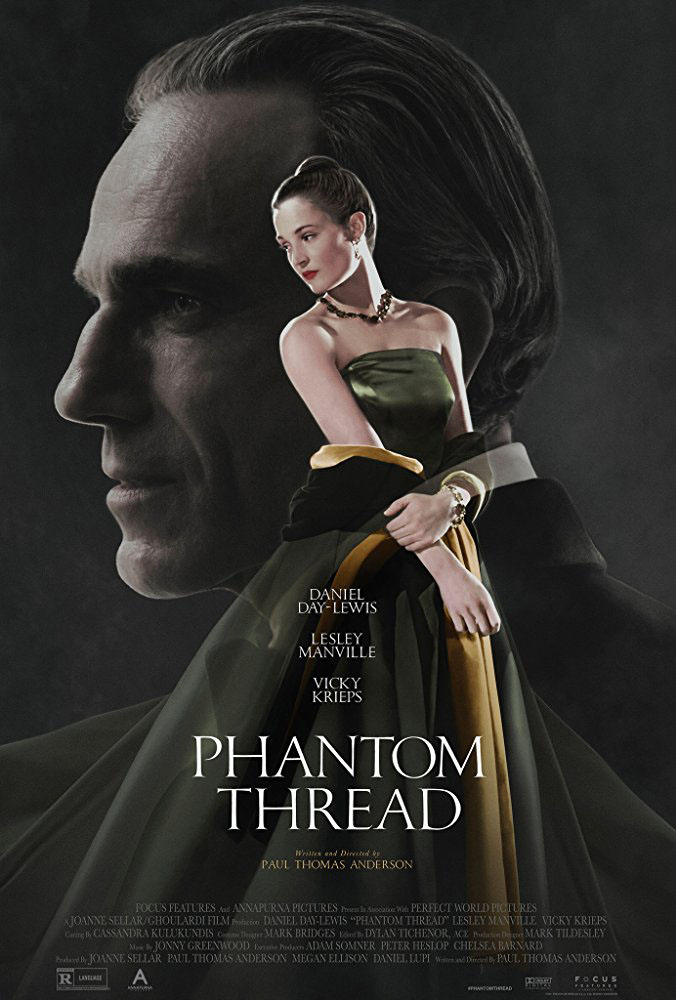

On the surface, “Three Billboards” and “Phantom Thread” do not seem to offer much in the way of conversations with each other. The former is a dark contemporary film with comedic undertones about a harried mother’s attempt to convince county police to investigate the rape and murder of her daughter. The latter is a film about a fashion designer in post-war England and his adventures in love. Beyond their shared Oscar hopes—both films are nominated for Best Picture—and the fact that they both star an Oscar winning actor, and are written by their directors, they seem divergent.

My initial interest in the duality of the films, though, was in the oppositional way their writer-directors exist within the films. PT Anderson is an American filmmaker and since his feature film debut in 1997 with “Boogie Nights,” he’s been focused on incisively assessing the dark underbelly of Americana. “Phantom Thread” is his first film to leave America. Martin McDonagh is an Irish playwright and filmmaker. “Three Billboards” is his second work to be set outside of Europe (“Seven Psychopaths” was the first), but the first to so virulently depend on its setting. In the artful buildings and bodies on display in “Phantom Thread” and in the open fields and dusty town in “Three Billboards,” setting is as much a character as it is a backdrop.

Oscar winners Frances McDormand and Daniel Day Lewis are the tense centres of their respective films. When the trailer for “Three Billboards” premiered a year ago, the film offered what seemed to be a quintessential film about Frances McDormand–known for her stone-faced wryness, and deadpan glibness–being Frances McDormand. This is not incorrect, although that estimation does not sound as generous as it is. As Mildred Hayes, McDonagh utilises a great deal of what marks McDormand as a significant actor among her peers. “Phantom Thread” plays to Day-Lewis’ skills in a less overt way. For all his chameleon like qualities as an actor, Day-Lewis is remembered more for blustering men like Bill the Butcher and Daniel Plainview than his more ironic turns. As Reynolds in “Phantom Thread,” he is both the exasperating thunderous male figure as well as the peculiar and sardonic one. The difference between the ways the two films utilise their star power is key to the way both films regard themselves.

On a larger note, both films depend on their subversion of the issues. The common thread they utilise is humour that is deliberately meant to be jarring and incongruous. The tonal shifts must work for the films to work. “Three Billboards,” in typical southern fashion, is less subtle about this use of humour. It’s one of the hooks from the trailers that the film deploys consistently, even if carelessly. Criticisms of the film’s carelessness with race relations have somewhat become conflated with discussions on the value of humour for tough situations. The conflation has been a misrepresentation. If “Three Billboards” suffers in its dramaturgical finesse, it’s in its unwillingness to really take its characters to task. Consider “Phantom Thread” and its flirtation with comedy. I would submit it is one of the funniest films I’ve seen all year, not in spite of but because of the way it remains unwilling to soften the edges or the nastiness of any of its

characters. Its ruminations on love is deeply unsettling. In one of its final moments, Daniel Day Lewis’ Reynolds murmurs to his paramour, “Kiss me, my girl, before I’m sick.” It’s a line that’s at once bizarrely (and frighteningly hilarious) in context as well as being marked by the romantic power of the words as text only. But Anderson, impressively, is reticent about commenting. It’s his insistence on not making this tale palatable that becomes the driving force. “Three Billboards” is hyper aware of the real world relations it faces – both in gender, class and race. Its coda, then, cannot help but feel slightly lacking considering all the build-up. McDonagh’s warm vision of the world (and for all the darkness inherent in his films, McDonagh has always been an optimist), seems incongruous with the singed exterior of the Missouri he’s given us so far. A more credible version of “Three Billboards” needs the nastiness at the centre—and the nastiness that builds its first act—to reach to a fervour not to descend into platitudes. Freed from the confines of contemporary expectations (“Phantom Thread” is not old enough to be historical, but set far enough in the past to be comfortably distant) Anderson is able to be freer about moralism. McDonagh seems confined by the contemporary.

As Oscar night approaches, “Three Billboards” (initially a sure-fire frontrunner) has become the source of much criticism as is typical of any Oscar season. Much of it surrounds the idea of the film’s inability to handle race well and also McDonagh’s inability to accurately or realistically imagine the (now extinct) town of Ebb, and the South at large. What happens when setting is so intrinsic to theme? And how does that affect our own interaction with art in such frayed times? “Phantom Thread” is not more rewarding only because Anderson is able to be more relaxed in the past. It’s also more compelling visually. “Three Billboards,” on the other hand, is often shot through a filter that makes it look dull and unwelcoming. But the question of suitability and appropriateness of who tells which stories will continue to reverberate.

It’s a shame both films only played for a week in Guyana. The audience I saw “Phantom Thread” with was particularly lively, even annoyingly so. There was a constant stream of running commentary from a row that particularly rankled. Halfway through the film, though, hardly impressed by it, I considered that it reflected a great deal on Anderson’s growth as a filmmaker. I would hesitate to call the film his finest, but “Phantom Thread,” for all its formalist structure and symmetry, is a surprisingly accessible film. “Billboards,” with and without its fault, offers a compelling view of small towns and corruption that might ring true in Guyana. As “Jumanji” enters into what seems like its 100th week in cinemas, it’s a shame audiences only had a week to journey to one of these other cities.

“Phantom Thread” and “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” played last week at cinemas in Guyana and will be released on DVD on April 10th and February 27th, respectively.