Before proceeding with today’s article, we refer to the Government’s announcement that nine companies are interested in the allocation of the remaining oil blocks and that it is exploring options for both direct engagement and selective bidding. The Petroleum Advisor to the President had advocated the application of competitive bidding procedures to avoid the risk of corruption. We fully support this approach which includes conducting detailed background checks of companies bidding for the oil blocks.

Before proceeding with today’s article, we refer to the Government’s announcement that nine companies are interested in the allocation of the remaining oil blocks and that it is exploring options for both direct engagement and selective bidding. The Petroleum Advisor to the President had advocated the application of competitive bidding procedures to avoid the risk of corruption. We fully support this approach which includes conducting detailed background checks of companies bidding for the oil blocks.

One of the interested companies is Petrobras, a Bra-zilian State-controlled company which was embroiled in the largest corruption scandal in the history of that country, that led to nation-wide protests in 2016 and contributed to the impeachment and subsequent removal of the Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. The scandal, uncovered during a money laundering investigation nicknamed “Operation Carwash”, involved inflating contracts for construction and service works and “kicking-back” the difference, estimated at US$3 billion, into the personal bank accounts of senior executives of Petrobras, certain political figures, and the ruling party to fund its election campaigns. We must therefore be extremely careful in our selection process and ensure that the terms and conditions of any new agreement represent the best interest of the country. In addition, we should endeavour not to repeat the mistakes we have made in relation to the Production Sharing Agreement with ExxonMobil. We must also ensure that the related legislation and regulations, including our Procurement Act, are revised or amended so that any decision on the allocation of the remaining oil blocks is supported by legislation.

The Auditor General has bemoaned the fact that his office’s budget for 2018 was reduced, which reduction he indicated would stymie his office’s preparation for the audit of the emerging oil and gas sector. It may be recalled that legislative measures were put in place since 2005 to ensure that the Audit Office is provided with adequate resources to discharge the Auditor General’s responsibilities. Second, the Auditor General announced that his office would be conducting a forensic audit of the Georgetown City Council at the request of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) although several years of the Council’s accounts are with his office waiting to be audited. Third, the Auditor General indicated that he was giving the Guyana Elections Commission (GECOM) more time to respond to his three reports alleging fraudulent practices. This prompted GECOM’s Chairman to issue a statement of condemnation of the Auditor General’s actions as they relate to GECOM.

Today’s article discusses the above three issues, their implication for the work of the Audit Office and offers some suggestions which the Auditor General may wish to consider, going forward.

The Audit Office’s budget

Section 40 of the Audit Act sets out the procedures for the preparation and approval of the Audit Office’s budget. It states that the expenditure of the Audit Office shall be financed as a direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, determined as a lump sum by way of an annual subvention approved by the National Assembly after review and approval of the Audit Office’s budget as a part of the process of the determination of the national budget. Section 40(2) enumerates the following steps:

(a) The Auditor General shall prepare, in accordance with the rules, procedures and guidelines set out in the Budget Circular, and submit to the PAC a budget for the Audit Office, including a work plan and programmes, for the next ensuing fiscal year;

(b) The PAC shall review the budget submission and provide comments for consideration by the Auditor General;

(c) After considering comments from the PAC, the Auditor General shall revise the budget submission and re-submit it to the PAC for endorsement;

(d) The PAC shall, no later than ninety days before the commencement of the next ensuing fiscal year, forward the revised budget submission for that year, together with its comments thereon, to the Minister of Finance for consideration and inclusion in the annual budget proposal; and

(e) The Minister shall include in the annual budget proposal a subvention for the Audit Office within the allocations of the Parliament Office to be voted on by the National Assembly.

An understanding of the way the national budget is constructed may be helpful. First, the amount of funds available to meet expenditure on public services, that is, the fiscal envelope, is determined by a combination of the accumulated surplus (if any) brought forward, the amount of revenue expected to be collected, and the extent to which there is likely to be a budget deficit. Of course, the priorities of the Government within a medium-term budget and expenditure framework must be taken into account. A comparison is then made with the budget submissions from all budget agencies. If the aggregate proposed expenditure exceeds the fiscal envelope, these agencies would be asked to rework their budgets, failing which the Ministry of Finance will have no other option than to adjust downwards the budgets of these agencies to conform to the requirements of the fiscal envelope.

The Ministry does not interfere with the proposed budgets of constitutional agencies, such as the Audit Office. However, if necessary, it makes a recommendation to the National Assembly which in turn makes a final decision on the matter. It therefore comes as a surprise that the Auditor General is complaining publicly that his office’s budget was cut by some $63 million. He is rather fortunate compared with his predecessor in that prior to passing of the Audit Act, the Audit Office was treated as a budget agency where the Ministry of Finance made the final decision on its budgetary allocation.

Auditor General’s mandate

The Auditor General’s mandate relates to the audit of the public accounts, and the accounts of statutory bodies, entities in which controlling interest vests with the State, and foreign-funded projects whether by way of loans or grants. His mandate does not extend to the auditing of the several statements and accounts that ExxonMobil is required to submit annually to the Government in accordance with the 2016 Production Sharing Agreement (PSA), as this will entail examining the records, transactions and related documents of Exxon, a private sector organisation.

The Auditor General, however, has the right to audit the revenue flowing to the Government from Exxon. In this regard, his approach should be one in which, having studied the PSA and the financial statements submitted by Exxon duly audited by an auditor appointed by the Minister responsible for petroleum, any concerns that he (the Auditor General) may have will have to be addressed to the Government. Based on the response received, the Auditor General can then prepare his report for inclusion in his annual report to the National Assembly. It is worth mentioning that Exxon’s statements and accounts will not be due for presentation to the Government until 2021, assuming crude oil production begins in 2020.

As regards the D’Urban Park Project, the Auditor General indicated that he had written to the private company established to execute the Project, seeking information to enable him to conclude his investigation. He had previously indicated that the results of the investigation would be included in his 2016 report to the National Assembly. That report was issued on 29 September 2017. The relevant section states that: (i) the Ministry of Public Infrastructure had expended amounts totalling $408.874M on the Project; (ii) at the time of reporting the Audit Office was conducting a special audit and a separate report would be issued; (iii) the Audit Office wrote the Ministry on 24 July 2017 requesting certain information; and (iv) a response was received on 26 July 2017 indicating that the Ministry was never involved in the documentation as it relates to the operation and formation of the company.

The Auditor General should be keenly aware that the company is not obliged to provide him with the requested information. His approach should therefore have been to request the information from the relevant government agency overseeing the project, and it is left to that agency to liaise with the company to provide the information. It will be close to three years since the Project was initiated, and it is time to move on. Accordingly, the Auditor General should close his investigation and finalise his report to the Assembly to allow for the PAC to decide on the next steps.

In passing, it has also been over two years since the Cabinet decided that the transactions audit of the National Industrial and Commercial Investments Ltd. (NICIL) be undertaken by the Audit Office. In this regard, we are still to hear from the Auditor General who should have declined the assignment, given that he had already audited NICIL’s transactions for the period in question, and his reports and opinions did not reflect any adverse comments.

Forensic audit of the Georgetown City Council

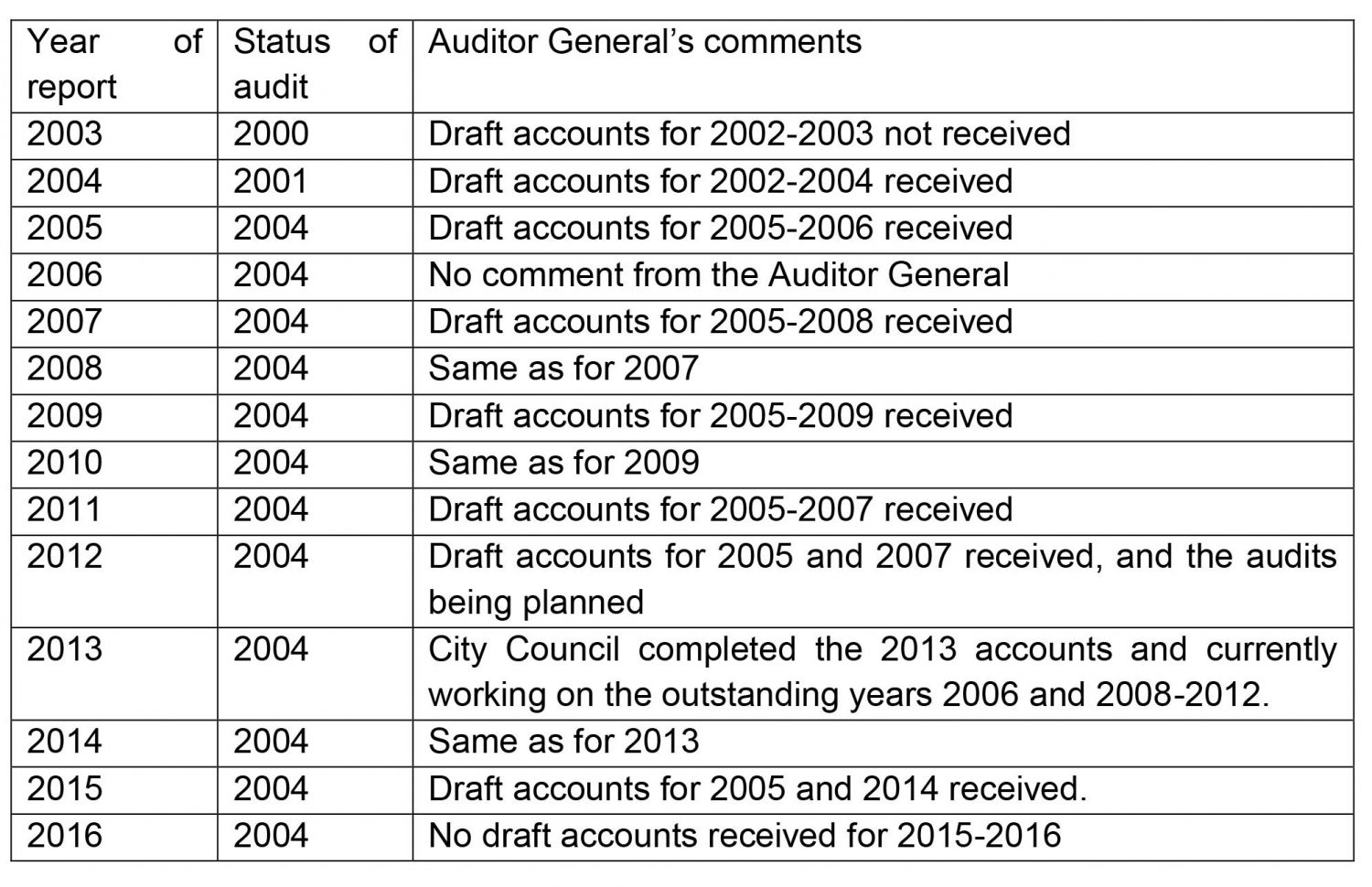

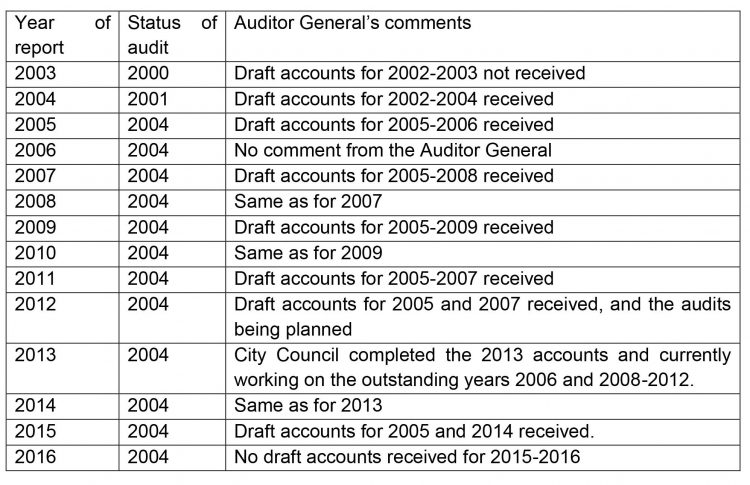

The following table provides the status of the audit of the Georgetown City as indicated by the Auditor General in his reports to the Assembly:

The last set of accounts to be audited and reported on was in respect of 2004. That audit took place in 2005, and despite the City Council submitting subsequent years for audit, there has been no further movement. As can be noted, there were some discrepancies in the comments of the Auditor General in relation to the submission of the draft accounts. Suffice it to state that the Council is 12 years in arrears in terms of having audited accounts. The Auditor General cannot escape blame for this state of affairs since as far back as 2005 he was in receipt of draft financial statements for subsequent years. The Audit Office has hundreds of draft accounts of the other five municipalities and well as the 65 Neighbourhood Democratic Councils still to be audited. The Auditor General has now announced that he would be undertaking a forensic audit of the City Council!

GECOM’s special investigations

In 2015, GECOM purchased radios, nippers and toners which were the subject of adverse comments from the Auditor General in his 2015 report to the Assembly. The Auditor General did indicate that at the time of reporting a special investigation was launched. The results of that investigation were reflected in his 2016 report. It has now come as a surprise that, after three years, the Auditor General is continuing his investigation. He has given GECOM more time to respond to his report. This prompted the reaction of GECOM Chairman who suggested that if the Auditor General has evidence of any fraudulent practice, he should use his powers and refer the matter to the Police.

Conclusion

Given his reporting relationship to the Legislature, the Auditor General should be guarded against making public pronouncements, especially on matters under investigation. He should let his reports speak for themselves, avoid “playing to the gallery”, and focus more on the display of quiet competence. The Auditor General has a considerable amount of outstanding work to perform, and his office has serious capacity constraints. As such, he should not seek to extend himself by seeking to undertake other activities without satisfactorily completing those relating to his core responsibilities.