Two American women who survived the Jonestown tragedy on November 18, 1978 have finally returned to Guyana to show appreciation and have dialogue with the residents of the mainly Amerindian community.

Laura Johnston Kohl, 70, and Jordan Vilchez, 60, journeyed to Port Kaituma last Tuesday, 40 years later, for a meet and greet and to answer tough questions.

They didn’t visit before because they tried to put the incident behind and not be reminded of that horrible day when the lives of over 900 people, including close relatives and acquaintances, were snuffed out.

In a tragedy that shocked the world, preacher and leader of the Peoples Temple, James Warren ‘Jim’ Jones coerced them to drink cyanide-laced cool-aid and end their lives. This was after he realized that his position was threatened when an investigation of the cult headed by US Congressman, Leo Ryan, started. As Ryan and the others reached the airstrip to fly back home after the investigation, members from the Peoples Temple drove up and opened fire. He was killed, along with three press persons and a member of the temple.

In March of 1977, Jones had asked Kohl if she would “come down to Guyana and help to get started for a big move. And in the summer of 1977, 400 people came. We had more people than we were ready for and so things were pretty primitive in Jonestown.”

She and Vilchez survived the tragedy because they were in engaged in activities in Georgetown at the time.

Kohl, who worked in the welfare department, lost her eight Guyanese children that she had adopted while Vilchez lost her two sisters and nephews.

In tears, an emotional Kohl told Stabroek News during an exclusive interview in Georgetown that: “It was such an oversight that we never talked to the Guyanese and we feel bad that there was never really a dialogue with the neighbours who were so kind to us.”

Damage

She was saddened that the incident has done so much damage to the reputation of Guyana which she said, was “like a paradise.”

She feels a sense of responsibility for what happened because she “did not watch” and wants to “address really hard questions like, ‘how did you let this happen…’?” They were full of praise for the Amerindians who had taught them to clear the jungle, farm and construct buildings when they first arrived.

Kohl told this newspaper: “it’s global that you have a leader who can motivate people to do things against their better sense and critical thinking.”

She and Jordan were both in Georgetown on the day of the mass suicide and they returned to the US without going back to Jonestown.

She feels that for too long they have talked about Jonestown as if it is all part of the United States and that it was time for the Guyanese perspective to be addressed.

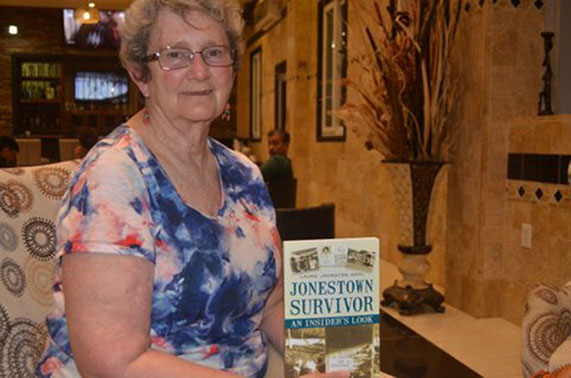

A middle-school teacher, she wrote a book in 2009 about the tragedy Jonestown survivor: An insider’s look and it was published one year later. She is also in the middle of her second book, which she hopes to finish by this summer. Kohl is also involved in civil rights articles for the local monthly Progressive Newspaper and for the Jonestown Report.

The team here included Laura’s husband, Ron Kohl; their son, Raul; researcher/photojournalist, Richmond Arquette; Kevin Kunishi, a photo-documentarian and an editor from Denmark, Rikke Wettendorff, who has been working on reports on the Jonestown survivors for several years.

Vilchez too has regretted the tragedy, which has “put Guyana on the map in a terrible way.” She always loved Guyana and found the people to be really warm. In fact, she still has a stack of letters from residents whom she communicated with.

She expressed appreciation to the Amerindians for helping them to survive in the jungle.

Fence

She had many thoughts about what it would be like to return and sat “on the fence for a while. Part of me felt that I survived so there was no point of me going back to the place where that happened.”

Vilchez, who lost her mother over a year ago, has gotten over that now and wanted “to be in the place and feel the ground where we were and feel the air and pay respects” to the victims.

She is currently finishing a book that she started two years ago while she is also involved in interior designing and multi-media art.

The women both felt that in spite of what members endured, they could not say anything because Jones “was protected by a code of silence. He was surrounded by people that did not let many things out.”

Unless you were really watching, there were things going on that were horrible but you wouldn’t really know about them.

They were merely “swept under the rug… and it kept getting worse but nobody was talking about those things…”

Kohl’s regret is that she did not watch him long enough to realize that the problems they noticed could never be fixed. “I thought that when we finished what we were building we would go back and fix the things. …We never knew that Jim was going to kill everybody.”

Although she described Jones as a con artist, she “did not notice it at the time and said that for some reason, the best people I knew in my life were part of the Peoples Temple group.”

Jones, she said was a drug addict and when he was “high and incoherent, the nurses never let him out of the house so we never saw him staggering. He was certainly a psychopath.”

Investigation

In October of 1978, they learnt that Congressman Ryan and others were coming to conduct an investigation of Jones and the Peoples Temple.

Realizing that he was under a lot of pressure, Jones had already “started his plan with the poison because he was not going to let anyone assault his authority.”

On the night of Ryan’s arrival, members put on a talent show, with performances including a live band and singing.

It was the next morning that Ryan and team asked the people “if they were happy there or wanted to leave. About 20 people came forward and that was what precipitated all of what ensued after,” Vilchez said.

“When people started to get the things together (to leave), Jones flipped out. He just could not let people go because he was a pathological narcissist. He took it so personally that it was like someone taking his arm.”

Ryan was then shot dead at the airstrip and the people were ordered to consume the poisoned drink.

Eleven other people, including Leslie Wilson – who visited Guyana two weeks ago -and her two-year-old son, survived the massacre. They had escaped Jonestown by pretending that they were going on a picnic on the morning of November 18, 1978. “They went to Matthews Ridge and someone put them up…” Wilson’s mother, sister, nieces and nephews were left behind and died.

According to Kohl, Jones’ decision to kill everyone must have been because he did not want others taking credit for Jonestown, even though there were people capable of taking over.

He never wanted to share his position and there was no transition plan.

She also felt that due to his mental illness he thought that nobody could do it like he could.

“He could be all things to all people; `if you want me to be your friend, I’ll be your friend, if you want me to be your father, I could be your father…’ or minister or even to be their God. However you needed to hear it, he could lie to you about that. He was extremely manipulative”, she said.

They could not trust anyone to talk about issues even if they noticed something was going wrong because word would get back to him.

Georgetown

Kohl felt that she was “allowed to work in Georgetown because Sharon Amos, another woman from the welfare department must have assured Jones that if she gave an instruction for me to kill myself, I was going to do it. I later realized that nothing was spontaneous; Jim planned everything.”

On the day of the mass killing, Amos received a call from Jones that people were dying. Kohl, unaware of what was taking place at the time, was sent across town to pick up Jones’ sons, Steven and Jimmy from a basketball game.

Then in a private discussion, Amos told Jones’ sons that they, along with the other members who were in Georgetown had to kill themselves. The boys bluntly refused the orders and told Amos not to mention it to anybody else in the house. Kohl recalled that they went out to a talent show with the People’s National Congress and when they returned, they found that Amos had killed herself and her three children. The Guyana Defence Force had already taken possession of the house by then.

Discomfort

Vilchez, only 19 at the time, recalled being afraid of Jones.

“I had an inside discomfort, which was scary because at the meetings people would be brought up on the floor for some infraction… I was always afraid that I would get brought up for something that I never knew may have been considered against the rules so I tried to be dedicated… That was very uncomfortable… It was tense and intense”, she said.

She added that if anyone dared to challenge Jones then other people, especially those closest to you would jump up and even engage in a physical confrontation with you.

It was because of those discomforts that she came up with the idea to speak to the business people about the Jonestown Agricultural Project and asked for donations. She then moved to Georgetown.

Just before the tragedy, her mother brought her [Vilchez’s] developmentally disabled sister from the US, to live in Jonestown.

Her mother spent a week and Vilchez travelled back to Jonestown to be with her. But when her mother left she was “just floating around Jonestown; I didn’t have a task.” She had to do something fast before she got assigned to some other task and lose the freedom that she had.

She then sought and was granted permission to go back to Georgetown with a group that was going. That was the day before Ryan and his team visited.

Vilchez also recalled that the guesthouse was built on deception, explaining that people pretended to heal others. She also recalled that when her mother visited, Jones made her and her sister pretend that they had boyfriends and that life there was normal. She also showed this newspaper a photograph of the boy who was supposed to be her boyfriend, sitting next to her. She said it felt awkward.

Some of the members found ways to defect and must have made complaints against Jones, such as him taking the social security cheques from elderly people for the temple, which among other things prompted the investigations.

This caused him to become increasingly paranoid. He made the members believe that “we had enemies and that they were out to get us. The truth is that investigators wanted to know what was going on within the temple and the investigations were about him.”

Vilchez said that being a revolutionary was talked about and that if people wanted to leave the group, Jones took it as a personal threat.

Those who did leave were called traitors, selfish, counter-revolutionary so because of that she “really felt like being dedicated and give it my all. Because of the influence, I felt that life on the outside would be empty and meaningless.”

Move on

When Kohl returned to the US, she tried to move on with her life and put the tragedy behind her. At first she helped some of the other survivors. Then she “didn’t know if to keep living or what to do.”

Instead she joined a different community where she got a lot of support. Then in 1998 she attended the 20th anniversary of the Jonestown tragedy and had conversations with survivors.

That was where they “placed all of the pieces together and realized how much problems we had missed – there was a big hole in my heart.”

She had loved Guyana and the tropics. Jonestown was multiracial and she loved that people “really wanted to make a difference in the world and do some sacrificing, whatever it took.”

Recounting how she joined the temple, she said that at age 22, while a college student in the 1960s, the American democratic system was scarred by the murders and assassinations of Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, John Kennedy and Malcolm X among others.

“That made me realize that you can’t be passive, you have to take charge because you don’t want the democracy to go down the drain… I realized that I had to make an impact on the world so I can stop that.”

Before joining the People’s Temple, she became part of the Black Panthers and the Wood Stock groups, but they did not work out.

“But then I came to California and met Jones. That seemed to be the answer. He seemed to be able to lead and be a vocal person to stop our society disintegrating,” she told this newspaper.

Drama

She recalled that he loved to create drama and that at a meeting, Jones “handed out juice and after they drank it he told that they have all been poisoned. Some of the people fell off chairs, as part of his drama.”

She noted too that to make his meetings exciting, he would jump off the stage in his robe or throw the Bible down. Kohl also remembered that at one time he made someone go out into the bush and fired some shots and pretended that there was a sniper.

She also said that some of the disciplinary methods at the temple were too rough, including spanking with planks.

In the case of Vilchez, she joined the temple in 1971 when she was 12 after a family friend raved about it to her mother. She went with her sister and her boyfriend and their two children for a meeting at the temple and saw that the people appeared to be very happy. She said that there was lot of singing. Jim was talking about issues of social justice. Her family had never been to a church because they were more political and progressive.

They had never seen a setting that was more integrated and lively and there was even a pool and it looked more like a community centre. As a 12-year-old, it seemed very inviting.

She travelled to Guyana the day after she heard she had to come, along with hundreds of others. She remembered being up until the wee hours of the morning working and attending meetings. She saw it as a way of him maintaining control and said he always needed people around him to plan. It was significant to know that all of the followers had different opinions about what was acceptable and what was not. According to her, the first role everyone had was to work in the field and that entailed waking up early in the morning.

She would pick up lunch, which consisted of a sandwich and a banana and tie it to her hip.

Wearing rubber boots, she toiled on the farm, planting cassava and eddoes. She did not like doing it but she “wanted to be a trooper and wanted to be proud that I was finally living the life of a worker in the field…”