Theodore Wilson Harris was born in New Amsterdam, British Guiana, and moved to the capital Georgetown after his father died in 1923. His mother married again, but his stepfather was lost, presumed drowned in the interior in 1929. These experiences were to become engraved indelibly in Harris’s consciousness for the rest of his life, particularly when coupled with his 17 years’ work as a government hydraulic surveyor through the rivers, rainforests and savannahs of Guyana. Those were haunting experiences from which his imagination and his writing drew infinite strength.

Sir Wilson attended Queen’s College, the country’s most prestigious secondary school for boys, and it was there that the first germ of an idea that he could be a writer entered his thoughts, when an English master, impressed by his class essays predicted, “Harris, one day you will be a novelist”. However, on leaving school, he trained as a surveyor. He married Cecily Carew in 1945, sister of Jan Carew who was also to be another foremost Guyanese writer. Harris was the father of E Nigel Harris, Chancellor of the University of Guyana and former Vice-Chancellor of the UWI; Denise Harris, a winner of the Guyana Prize for First Book of Fiction; Alexis and Michael Harris; all from his first marriage which ended in divorce. After relocating to England in 1959, he was remarried to Margaret Whitaker, a native of Edinburgh, Scotland, with whom he lived for 50 years until her death in 2010.

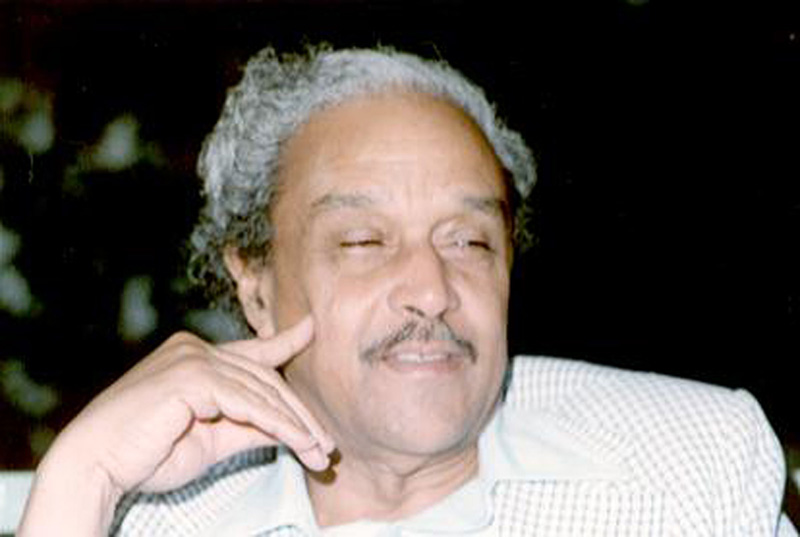

Harris was a novelist and short story writer, a poet, playwright, literary critic, essayist, and critical theorist. He was mostly known for the extraordinary innovation and breadth of vision, and the abstract complexity of his novels. Yet, he started his writing career as a poet, regularly publishing several poems and a few short stories in the newly established Kyk-Over-Al, edited by A J Seymour, in the 1940s. He was very prolific, and stood out as one of British Guiana’s foremost poets. His first collection was self published in 1954 – Eternity to Season ‒ containing poetry and a short play set in Canje, a location in which he once worked tracing the course of the river through extensive swamp lands, an experience on which he also drew for his novel, The Secret Ladder (1963).

As a poet, he was already demonstrating his independence as a writer, notably departing from the strict conventions of the time, and his interest in the classical mythology most evident in Eternity to Season. He was very much a part of the pre-Independence national literature that was developing in that period, associating closely with Martin Carter and others who regularly gathered for literary sessions in the 1950s.

It was after he left for England in 1959 that he published his first exceptional and ground-breaking novel, Palace of the Peacock, in 1960. This was followed rapidly by The Far Journey of Oudin (1961), and The Whole Armour (1962), set in the Pomeroon riverain area, two particularly outstanding examples of the Romance novel; then The Secret Ladder, distinguished by its semi-autobiographical content. Harris admitted to including real encounters while leading a government hydraulic surveying team in the Canje region.

As a truly extraordinary first novel, Palace of the Peacock stands out for its breath-taking originality and risk-taking independence. It revolutionised the form of the novel with its intensely dreamlike and often vivid imagery, innovative narrative style, post-modernism and advancement of post-colonialism in English fiction. The highly poetic streams of consciousness and dream quality reflect the influence of C G Jung and Freud which reappear in some later works, such as The Carnival Trilogy (1993).

Remarkably, British critic Kathleen Raine has written of Harris, that he not only revolutionised English fiction, but rescued it from staleness, and gave new life to the “English novel that had remained static for 100 years”. Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey recounted how he served as a reader for Faber and Faber, who asked his opinion of the unusual manuscript of Palace of the Peacock. He strongly recommended it, writing a convincing case to Faber that despite its daunting departures from the known narrative procedures, it was very important and a necessary act for them to publish it to support and advance originality and innovation in the literature. Faber not only accepted the manuscript, but remained faithful throughout, publishing all of Harris’ 26 novels, including reprinting the first four under one cover as The Guyana Quartet.

However, Sir Wilson’s output was not limited to the preoccupations and bewildering styles of Palace for which he is best known. The second half of the decade of the sixties and moving into the seventies saw a somewhat diversified range of interests. Harris deepened his excursions into the Guyanese interior, producing a series of fiction reflecting Guyanese Amerindian literature, ethos, cosmos, myth and experience. His output included short stories of the ilk of ‘Kanaima’, among the best examples of fictionalising the Amerindian world picture. This interest was to continue in later novels such as the figure of Canaima in The Four Banks of the River of Space (1990). During that period Harris produced works including The Sleepers of Roraima (1969), Age of the Rainmakers (1971)and Tumatumari (1967).

As his diversification continued, Harris was also to shift his strategy of novels that used his native Guyana as a setting for his human concerns. He produced five novels set in other countries, notably Scotland, England and Mexico. These, however, might not have revealed the extent to which Harris drew on autobiography for so much of his fiction. Black Marsden (1972), might well have grown out of his visit to Scotland, and furthermore it is set in Edinburgh, the birthplace of his wife, Margaret. Moreover, Harris himself describes as a “strange sequel to Black Marsden”, his novel set in Mexico, Companions of the Day and Night (1975). This was without doubt inspired by a visit to Mexico with Margaret during which he toured Mexico City, but more importantly the ruins of the ancient Aztec civilisations as well as sites and monuments of the Roman Catholic Christian heritage in which he took an interest.

Companions of the Day and Night is further testimony to Sir Wilson’s very deep explorations of the ancient pre-Columbian Americas – the mythology, the culture and the spiritual ethos. His broad research takes in the history of conquistadors Cortez and Pizarro out of which came extensive writings and philosophical thought that govern some of Harris’ post-colonial theories about literature, fictional narrative, history and culture. This novel, however, fashions a bridge into the Christian roots and rituals. It dramatises the posada ritual, an ancient tradition around Easter – a carnivalesque passion play in which Harris became interested during that Mexican tour.

Another of the novels set in the UK is Da Silva Da Silva’s Cultivated Wilderness (1977) which, again, was inspired by the author’s personal life and experience. Like Harris, the hero Da Silva is an artist and the setting is Holland Park in London where Harris lived for a long time before moving to his permanent home in Chelmsford, Essex. This novel was converted into a film done for showing by the BBC and was partly shot in a “prettyish kind of little wilderness” in Holland Park where the author had personal experiences.

Harris was to return to using the Guyana setting as a launching pad from which to articulate universal concerns when he wrote Carnival in 1985. He then became the first winner of the Guyana Prize for Fiction when the Guyana Prize for Literature was launched in 1987. Carnival was followed by The Infinite Rehearsal (1987) and The Four Banks of the River of Space (1990) all of which are grouped together and reprinted under one cover by Faber as The Carnival Trilogy (1993). But a fourth book – Resurrection at Sorrow Hill (1993) fits very neatly with this trio to make up a virtual second highly acclaimed and important foursome after The Guyana Quartet.

It is here that Harris best reproduces the post-modernist form started in Palace of the Peacock. It is the writing style that critic Michael Gilkes called “maverick” and which has been described by others as “abstract and densely metaphorical”. While in Palace Harris employs narrators who separate from and merge into each other, a tyrannical materialist exploiter Donne and his more humanitarian brother who is a “dreamer”. In the Carnival Trilogy he introduces the experimental “fictional autobiography” told by “W.H.” the fictional representation of Harris himself. Here is where Harris’ journey is reminiscent of Dante and his Divine Comedy.

The trilogy embarks on excursions into the Guyanese interior where the fascinating landscape and the cosmos are intensely treated as one. The Harrisian landscape is extensively studied by Mark McWatt for whom the landscape is another character, merging in with victims of exploitation. These are further Guyanese post-colonial works interrogating the environment, as Harris articulates a concern for the survival of humanity: the rainforests, conservation as against exploitation and the self-annihilating history of man. All peoples, races are one as Harris believed in cross-culturalism as opposed to multiculturalism, but history is the repeated confrontations of man with himself wearing different masks and costumes and destroying himself in wars, genocide, colonisation and conquests as represented by the likes of Cortez and Pizarro.

Harris employs the metaphors of classical mythology, including his repeated use of “the beggar is king” drawn from the return home of Ulysses (Odysseus) disguised as a beggar. His was a virtual resurrection as he arises from his own presumed death – an image of rebirth very often recreated by Harris. The Resurrection At Sorrow Hill is yet another example of this recreation of history. Sorrow Hill is a community in Bartica in Guyana which is the gateway to Essequibo and the vast interior of the country. Ironically, Sorrow Hill is also the name of a cemetery in Bartica.

Sir Wilson’s training and work as an applied scientist was to have yet another effect on his writing. His innovative and uncompromising imagination drove his creation of narrative strategies borrowed from science, including quantum physics and the mathematical theory of Chaos. The author himself used the term “quantum fiction”. His novel Jonestown (1996) is based on the notorious massacre of some 900 members of the People’s Temple in the Jim Jones settlement in the remote North West of Guyana. Harris does not attempt to present an account of the suicides and mass murders, but focuses on a traumatised hero who survived the horror as well as a Jim Jones character among the dramatis personae. This, which has been called Harris’ best-selling novel, is also the best example of the application of Chaos and quantum theory.

Harris grew to be so highly celebrated, so internationally acclaimed, that a virtual critical industry developed around him and his work in the UK, Europe and the USA. He accumulated honours, including major international conferences and publications on his work, such as a dedicated issue of the prestigious American journal Callaloo. He was knighted by the Queen in 2010 “for service to literature”. He won The Guyana Prize 1997 for Carnival, and again the Special Award in 2002 for The Unfinished Genesis of the Imagination. Honorary doctorates were conferred upon him by many universities, and he was more than once nominated for the Nobel Prize. Collections of critical writings on his art and his own essays abound in such publications as The Uncompromising Imagination (1991), The Womb of Space : The Cross-Cultural Imagination (1983), ‘Tradition, the Writer and Society’ (1967) and ‘History, Fable and Myth in the Guianas and the Caribbean’ (1970).

Among his closest associates, friends and editors were Warwick scholars Michael Mitchell and David Dabydeen, Hena Maes Jelinek of Liege, Nathaniel Mackey and Andrew Bundy. His most recent novels include The Dark Jester, (2001) and Mask of the Beggar, (2003); and his most obvious semi-autobiographical work, whose title draws its image from Ulysses’ return home, The Ghost of Memory (2006).

(Al Creighton, Jr, University of Guyana)