Gemma Robinson teaches at the University of Stirling, Scotland. She is researching Wilson Harris’s poetry, and is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).

Gemma Robinson teaches at the University of Stirling, Scotland. She is researching Wilson Harris’s poetry, and is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).

In the quiet atmosphere of the A. J. Seymour Room at the University of Guyana Library there are at least a dozen copies of Eternity to Season. This 64-year-old book of poems was written by Wilson Harris, the visionary writer who died this month aged 96. It is a book I know well, but do not own. You can no longer buy this edition, and to read it I look at my own beloved dog-eared photocopy. Books and bookshelves can tell a story about Guyanese literature and literary relationships. But what kind of story should this one tell?

It would be easy to find in these unsold books a metaphor for a disregard of creativity within our wider world of cares. But a pile of unread books can also be a symbol of potential and expectation – a sign of the longevity of art and its power to be brought to life when readers and the right circumstances come together. A stack of books can also be a sign of hope for artists and creative communities. Seymour had a profound faith in Harris’s creative vision, and was instrumental in getting the book published. This faith was well-rewarded. Harris was one of the major contributors to Kyk-Over-Al (the cultural journal that Seymour founded), and Harris found a publisher for his work: his 24 novels, beginning with Palace of the Peacock (1960), were published by the London-based Faber & Faber. Eternity to Season continued to live in Harris’s mind, and was reissued by New Beacon Press in 1978.

The life of a writer is precarious. Harris was 39 and then living in London, when Palace of the Peacock appeared. In a note written by Harris, housed in the A. J. Seymour papers, he admits that he ‘always had difficulty in securing publication for poems or short stories until “Kykoveral”’. He submitted work to the first 1945 issue: ‘Tell Me Trees, What Are You Whispering?’ – a poem that ‘had been turned down 2 or 3 years earlier by Chronicle Christmas Annual’. The possibility of this rejection now seems astounding, and was perhaps a sign of ‘the old complacent order’ that Derek Walcott suggests Harris was writing against. What is clear is that Kyk-Over-Al provided a literary life-line to the 24-year-old Harris. ‘Tell Me Trees! What Are You Whispering?’ is a lyric poem, both unexpected and familiar in its approach to nature:

I and the leaves will always lie together

And know no parting.

It is so strange

Standing here

Beneath the whispering trees

Far away from the haunts of men

Tell me, trees!

What are you whispering?

Here are the earliest signs of Harris’s wish to bridge the human and extra-human in his work, to take the ‘strangeness’ of our shared world and build a language that could help us see and hear its multiplicity. In a later essay Harris would comment that his creative task was to ‘revisit cradles of living landscapes and seek bridges across chasms of reality’.

Like many Caribbean writers and artists of his generation, from Derek Walcott to Martin Carter, Harris used self-publication to sustain his creativity. Harris’s early choice of pen name, Kona Waruk, fits his sense of wanting to develop an open environmental creative consciousness. Harris’s choice comes from the river, Konawaruk, a tributary of the Essequibo. It seems both a modest alliance of writer to place and a radical aligning of poetic voice to an environmental perspective. Used for his first two poetry pamphlets, Fetish (1951), and an earlier version of Eternity to Season (1952), this very local name clashes with and complements the symbolisms of his work.

In 1952, Harris attempted to explain the coherence of his poetic vision to Seymour. He wrote in a letter that he was ready in Eternity to Season ‘to meet the problem of a new world certain of the raw material of energy (psychological and creative) with which to build a structure truer to man’. The poems in Eternity to Season were ambitiously titled ‘Troy’, ‘Behring Straits’ and ‘Amazon’, suggesting that ‘the problem of a new world’ required a style informed by a mythic, social and environmental geography. It would encompass Greek myth and the fall of civilisations, as well as appreciating prehistoric patterns of migration, such as those that brought animals, plants and humans across the Bering land bridge.

The poetic voice in ‘Amazon’ speaks of ‘the world-creating jungle’:

The world-creating jungle

travels eternity to season. Not an individual artifice—

this living movement

this tide

this paradoxical stream and stillness rousing reflection.

The living jungle is too full of voices

not to be aware of collectivity

and too swift with unseen wings

to capture certainty.

The Amazon is many things to Kona Waruk – it is river, region, tide and ‘paradoxical stream’. The poem also creates an imaginative geography or dream map where we are pushed to view the Amazon in ways that exceed our documentary senses. Indeed documentary realism would never be enough in Harris’s view to help us build a new world. For Harris, we are living from ‘eternity to season’ – within the world’s ever-turning ecological cycles. The internal rhyme in the phrase reinforces connection, and encourages us to move down the poem to the jungle’s ‘collectivity’ and voices too multiple to ‘capture certainty’. Harris’s new world asks us to reset our short-term thinking, and imagine the ever-present multitude of life, and see ourselves within the vast ecology, mythology and history stretching between the Amazon and Troy.

In contrast to this ‘full’ living landscape, human material existence in this poem is rendered as torture ‘distorted into material duration and strife. / This is the glorified individual creation of antagonism’. Writing as Kona Waruk, Harris throws off human conflict and becomes a fluvial voice, a river travelling through ‘the world-creating jungle’ and between the locations and myths of ‘Troy’, ‘Behring Straits’ and ‘Amazon’. Here in these poems are the beginnings of Harris’s recurring themes: the reinvention of apparently static myths and histories; the freedom of association that he believed could create bridges ‘between man and man – and between man and his environment, the world’; and the urgency of moving beyond our ‘closed minds’ and ‘closed worlds’ to understand the cross-cultural community of our shared past, present and future.

To think about the unity (and disunity) of the Caribbean is one of the defining questions of Caribbean arts. Kamau Brathwaite imagines the wholeness of ‘the Archipelago’ as ‘the curve’ sweeping from Florida to the Amazon and Brazil, refiguring the region out of an apparently fragmented geography. ‘The unity is submarine’, he writes. Earlier in 1956 Harris proposed something similar:

The great backbone of America has valleys under the sea, and peaks which are islands in the Caribbean. In what seas shall we find that ancient mountain range that rode once without a flow between the extreme points of North and South America?

Written for a radio programme titled New World of the Caribbean, Harris was one of the first Caribbean writers to prompt a focus on submerged forms of unity. Trained as a surveyor and experienced in charting the rivers and landscapes of Guyana, he writes another version of the Caribbean seeking to understand the Americas in terms of geology. But this was not enough. The realities that geology and hydrography described helped to show Harris that he also needed to develop a ‘literacy of the imagination’. Arts and sciences were both required in his ‘cross-cultural’ poetics’ – a term that extends to consider the infinite connections between apparently different cultures crossing new and old worlds. It was a commitment to seeing the full scale of existence.

Over his long career Harris would absorb a phenomenal set of vocabularies to elaborate his creative practice, from archaeology, music, history, to quantum physics, cosmology, geology and Jungian psychoanalysis. His novels would occupy multiple imaginative geographies within Guyana, England, Scotland, Mexico and beyond. His critical essays would become touchstones for international critical communities seeking to understand postcolonial cultures and the demands of decolonising minds and institutions. At core his working life in Guyana as a surveyor had schooled him to question how we see the world. In 1964 Martin Carter, Harris’s friend and near contemporary wrote: ‘I know that the psychological squalor of everyday life is exhausting. I know that the urgent practical problem of making a living comes first. What I do not know is why only so few revolt, either by word or by deed against such acute spiritual discomfort’. The protesting Carter and Harris were not opposites. Harris proposed nothing less than a revolution by word, and through those words challenged us to examine our being and meaning in this world.

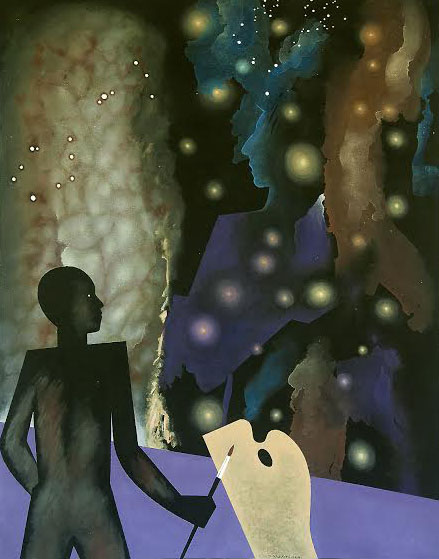

Different generations have responded to Harris and this challenge. Derek Walcott’s poem ‘Guyana’ creates Harris as the timeless surveyor. Fred D’Aguiar has spoken about how Harris’s exploded realism offered him a personally sustaining dimension beyond the racist realities of London. In his novel, Our Lady of Demerara, David Dabydeen created two priests – Father Wilson and Father Harris – mischievously and poignantly embodying the author’s multiplicity. George Simon’s glorious mural, Palace of the Peacock (2009), pays homage to the complex layering of realities in Harris’s fictions. Stanley Greaves’s Dialogue with Wilson Harris (2014), a series of 24 paintings, shapes and colours the metaphorical densities of Harris’s novels: the effect is to witness the intimate and sweeping scales found within new myths of the human, land, sea, cosmos and belonging. In Artist and the Mother of Space (prompted by Harris’s The Mask of the Beggar) a stylised figure is framed as creator and in conversation with the creating universe.

When news of Harris’s passing came, a younger generation on social media quickly named Harris’s place in their lives. Gaiutra Bahadur, author of Coolie Woman, wrote ‘Rest in power, Wilson Harris’, quoting his work on cultural bridging: ‘Our humanity is impoverished when we seize on either tradition or identity…I am not interested in a multi-cultural community but in a cross-cultural community, in ways in which a myth in one can find parallels in the other’. Trinidadian poet, editor, and curator, Nicholas Laughlin, returned to Harris’s novel, Palace of the Peacock, with the quotation, ‘The map of the savannahs was a dream’, adding, ‘There is no writer who has perplexed me more, in every essential and electrifying way’. Shivanee Ramlochan, author of Everyone Knows I am a Haunting, wrote simply, ‘Thank you, Wilson Harris, for the hinterland’.

Harris’s final home was in Chelmsford. He shared it with Margaret, his wife and fellow poet. The study was at the top of the house, with a view that is typical for many houses and suburban landscapes in the South East of England. But with Harris you knew that he always saw much more. Question the surface of your known world – his work constantly teaches us – voyage mindfully, listen harder, seek what is forgotten, endangered, and you will see a horizon teeming with companions, a world of ‘bridges across chasms’.

*****

Wilson Harris’s contributions to Kyk-Over-Al can be read in the Digital Library of the Caribbean: http://www.dloc.com/. His novels are published by Faber & Faber and Peepal Tree Press.