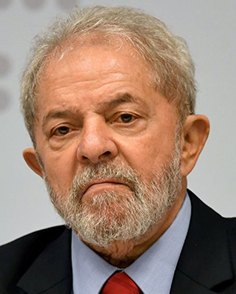

BRASILIA, (Reuters) – A Brazilian judge yesterday ordered former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva to turn himself in to police within 24 hours to serve a 12-year sentence for a graft conviction, likely ending the presidential front-runner’s hopes of returning to power.

Lula was convicted last year for taking bribes from an engineering firm in return for help landing contracts with state-run oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA.

Earlier yesterday, Brazil’s Supreme Court rejected Lula’s plea to remain free until he exhausts all his appeals, in a case he calls a political witch hunt.

The ruling likely ends his political career and blows October’s election wide open.

Technically, Lula could still run. Under Brazilian electoral law, a candidate is forbidden from running for office for eight years after being found guilty of a crime. But some exemptions have been made in the past, and the ultimate decision would be made by the top electoral court if and when Lula officially files to be a candidate.

But that is considered unlikely and Brazilian financial markets rallied on Thursday after the Supreme Court decision, which increased the chances a market-friendly candidate will win the election, according to analysts and political foes.

A defiant Workers Party, founded by Lula, said its supporters would take to the streets to defend his right to run. The party called for a Thursday night rally near Lula’s home.

“Lula continues to be our candidate, because he is innocent, and because he is the leading candidate to become the next president of Brazil,” said Workers Party leader, Senator Gleisi Hoffmann.

Federal Judge Sergio Moro, who has handled the bulk of cases in Brazil’s biggest anti-corruption effort, ordered Lula to turn himself in by late Friday afternoon. In a court document, he wrote that Lula should not be handcuffed and would have a special cell in the southern city of Curitiba.

Lula led Brazil in two four-year terms as president, from 2003 to January 2011, years of prosperity that were fueled by a commodity boom. He left office with an approval rating higher than 80 percent.

His endorsement was enough to get his hand-picked successor Dilma Rousseff elected twice. She was impeached and removed from office amid corruption scandals and economic crisis in mid-2016.

Now, his backing for a candidate would not be enough, analysts said, adding that voters will likely abandon his party in droves when they see that its charismatic leader was no longer in the game.

“The Workers Party will have to move quickly to Plan B, which is former Sao Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad, or even Plan C to back a leftist from another party like former Ceara state governor Ciro Gomes,” said Lucas de Aragao, a political analyst with Arko Advice in Brasilia.

Opinion polls show that Gomes and environmentalist Marina Silva would gain the most from Lula not running in October. Extreme-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro, who is polling in second place, has largely focused on anti-left rhetoric and may need to find a new line of attack.

Disarray on the left could improve the chances for a centrist such as Geraldo Alckmin, governor of Sao Paulo, Brazil’s richest state, and candidate for the powerful Brazilian Social Democracy Party.

Center-right President Michel Temer is mulling a bid but has record unpopularity in opinion polls after his austerity program aimed at putting Brazil’s overdrawn fiscal accounts in order.

“Lula leaves no political heir and much of his electoral capital cannot be transferred,” said Leonardo Barreto, with the Brasilia-based political risk consultancy Factual. “This can only help candidates who advocate continuing the reforms.”

Alckmin lamented the prison order against a former president but added in a Twitter message: “I believe this reflects an important change underway in Brazil: the end of impunity. The law is the same for everyone.”

Some observers fear that putting Lula in jail will turn him into a martyr and keep him in the public eye.

“The prison order against Lula will scramble the electoral process even more by putting him in the spotlight,” said Fitch Ratings director for Brazil, Rafael Guedes.