The essential fact is that this Committee is a Committee of the House responsible to the House as a whole, and is not a battleground for party faction…. I believe it is true to say that the authority of the Committee is greatly enhanced by its unanimous character and I hope the complete objectivity of its report. It is fair to say that many Honourable Members of both parties have made great endeavours and have sometimes sacrificed personal views to ensure that this shall be so.

The essential fact is that this Committee is a Committee of the House responsible to the House as a whole, and is not a battleground for party faction…. I believe it is true to say that the authority of the Committee is greatly enhanced by its unanimous character and I hope the complete objectivity of its report. It is fair to say that many Honourable Members of both parties have made great endeavours and have sometimes sacrificed personal views to ensure that this shall be so.

The late Sir Harold Wilson, Chairman of the

UK Public Accounts Committee 1959-1963

The Minister of Finance recently announced that the Government has so far received an amount of US$36,169 in interest by investing the Exxon signature bonus of US$18 million overseas instead of placing it into the Consolidated Fund where no interest would have been earned. This statement is, however, not entirely accurate. Had the decision been taken to place the money in the Consolidated Fund, the local currency equivalent would have been credited to the Fund, and ownership of the foreign currency would have passed to the Bank of Guyana, a State-owned entity. The Bank would then include the amount in its portfolio foreign assets which it invests overseas in keeping with its normal Central Bank operations. At the end of the year, the Bank transfers 90 percent of its net profits to the Government via the Consolidated Fund, as provided for by the Bank of Guyana Act. The effect is almost the same in terms of the return on the investment, with the added assurance that there will be no violation of Article 216 of the Constitution and Section 38(1) of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act. That section states that, “all public moneys raised and received by the Government shall be credited fully and promptly to the Consolidated Fund…” (emphasis mine). To the extent that the signature bonus is kept outside of the Consolidated Fund, both a constitutional and legislative violation continues to take place.

The Minister explained when the funds are needed, a Supplementary Estimate will be tabled in the National Assembly requesting authorization of the use of the money after which transfers would be made to the Consolidated Fund. However, as the guardian of the Consolidated Fund, the Assembly is unlikely to authorize the withdrawal of any earmarked funds unless they are first placed into the Consolidated Fund. In 1999, the previous Administration had given a similar assurance in relation to the Lotto Funds which were held in a special bank account at the then Office of the President and used to incur expenditure without parliamentary approval. That assurance was honoured in the breach up to the time it vacated office in 2015.

Last week, the Department of Public Information issued an article in which the Minister of Public Health is reported to have challenged an Opposition member of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) to contradict her claim that there was never in recent times a similar partisan approach to the work of the PAC. She asserted that “I have been the Chair of this Public Accounts Committee and there was never a time when the Public Accounts Committee has done its work without full collaboration with both sides of this House, and I say it without fear of contradiction. Because we focused on the issues, we saw it as a national issue, and we had to address it so that we can make the accountability within every agency in this country done in accordance with the rules and regulations.”

The above statement does not augur well for the effective functioning of the PAC. It is for this reason that we have chosen to quote the words of the late Sir Harold Wilson in the hope that they will serve as an important reminder to PAC members as to how they should view their role in the public accountability process. After a testy start of the examination of the public accounts for 1992, the PAC members settled down and generally

discharged their responsibilities with objectivity and in a non-partisan way. The names of the late Winston Murray, Dunstan Barrow and Dr. Moti Lall should not be forgotten, to which we must add the late Reepu Daman Persaud in the pre-1992 period.

However, throughout the entire post-Independence period, the effectiveness of the work of the PAC in seeking to hold successive governments accountable has been adversely affected by the lack of timeliness of its examination and reporting, resulting in not only a build-up of backlogged accounts to be examined but also the findings and recommendations of the Auditor General repeating themselves in successive reports. The latter did not escape the PAC’s observation in its 2000-2001 report although it was made in the context of significant delays in the issuing of the Treasury Memorandum.

The PAC examination of the public accounts is now open to the public. This is a progressive development since the public has an opportunity to witness some of its elected representatives in committee at work, either directly or through the reporting mechanism of the media. With the full glare of the public eye, the need for members to conduct themselves befitting of the position they hold and to avoid the display of partisanship, cannot be over-emphasised.

The Auditor General, for his part, walks a thin line, and must always be cognizant of how his audit examination and reporting of the results are interpreted. He must at all times be, and seen to be, objective and consistent in his approach regardless of which Administration is in place. His allegiance is to none other than to the Constitution to which he swore allegiance.

Trends in Reporting by the PAC

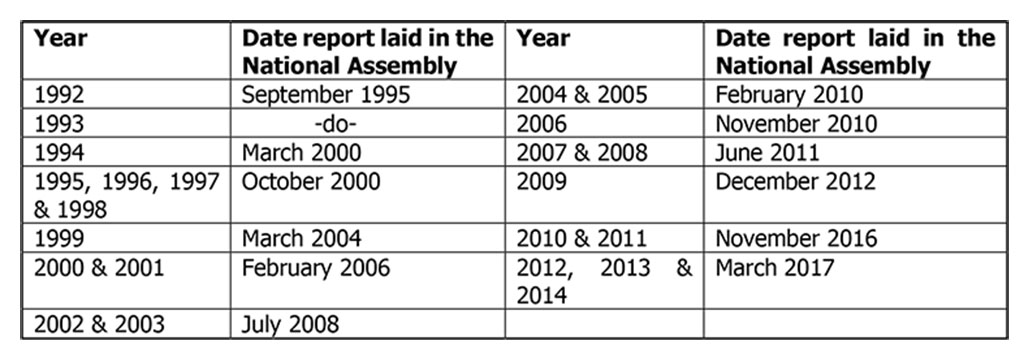

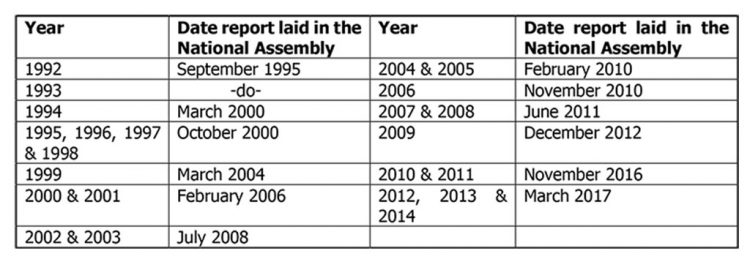

In an attempt to address the backlogged accounts to be examined, over the years the PAC took the unconventional approach of examining and reporting on a number of years together, as shown below.

From the above table, one can calculate that it took on average three and one-half years after the issuance of the Auditor General’s report, for the PAC to complete its examination and reporting back to the National Assembly!

From the above table, one can calculate that it took on average three and one-half years after the issuance of the Auditor General’s report, for the PAC to complete its examination and reporting back to the National Assembly!

While we may feel satisfied that there is annual financial reporting and audit, have we really paused to reflect on the quality of the reporting and the extent to which the Government has discharged its stewardship and accountability responsibilities? In his 2014 report, the Auditor General disclaimed his opinion on four of the consolidated financial statements submitted because of reservations of a fundamental nature while for the remaining eight statements, he qualified his opinion on them because of reservations/disagreements of a material nature. In other words, none of the financial statements constituting the public accounts were given a ‘clean bill of health’. For 2012 and 2013, the Auditor General made a similar assessment of the public accounts.

While we may not agree with the Auditor General’s assessment of the public accounts having regard to his findings, the PAC has failed to address the issue in an effort to have the Government taking corrective action so that the public accounts can be given ‘a clean bill of health’. In the private sector, the auditors’ slightest qualification of opinion usually results in a shake-up of top management. Indeed, reputable companies would do everything possible to avoid receiving a qualified auditors’ opinion on their accounts.

The latest PAC report represents the seventh time since the restoration of public accountability in 1992 that there was combined reporting involving a number of years notwithstanding that for most of the years, the Auditor General issued his report within the statutory deadline of 30 September. For his part, the Auditor General did not help the cause of the PAC since his reports have been too lengthy and covered too many minor observations that are in the nature of internal audit findings. The PAC’s examination was therefore rendered extremely tedious and time-consuming in its attempt to identify the material findings and their related impact. Indeed, the PAC is on record as having expressed its dissatisfaction about the length, quality and structure of the Auditor General’s report. In its 2010-2011 report, the PAC expressed concern about the “volume of the Auditor General’s report and the variability in the significance of the points being raised”. Accordingly, it recommended that the language used in the report should address the specifics of the issues raised and thereby giving clarity to details. In its 2012-2014 report, the PAC recommended that the language used in the Auditor General’s report should be consistent throughout the report.

Key Findings in the PAC’s Report for 2012-2014

The key findings, as reflected in the above report, are follows:

(a) Across Budget Agencies, Accounting Officers and engineering staff appeared to persistently sign off incomplete projects;

(b) Accounting Officers were not implementing measures to avoid the recurrence of overpayment in its entirety;

(c) Performance bonds and insurance were seldom utilised as surety against

substandard and incomplete work done by contractors;

(d) Accounting Officers were continually having staled-dated cheques in their

possessions;

(e) There was persistent non-adherence to the Stores Regulations;

(f) They were instances of monies not refunded to the Consolidated Fund;

(g) There existed a failure by some subvention agencies to submit financial

statements;

(h) Logs books were not properly maintained across agencies;

(i) Some Accounting Officers appearing before PAC were not properly prepared for

the deliberations;

(j) The issue of outstanding cheque orders persisted, especially in the Regions;

(k) Outstanding police reports for incidents reported continued to be a challenge;

(l) Missing File Jackets for Court cases cited in the Auditor General’s Report

continued to be a challenge;

(m) Frequent use of sole sourcing as a part of the procurement system;

(n) Accounting Officers were not adhering to recommendations by the Committee

to address repetitive challenges;

(o) Performance bonds, mobilisation bonds and insurance were not extended for

life of projects;

(p) The Regions continued to have a number of vacancies yet to be filled; and

(q) Expired drugs were donated to the Regions.

Readers who over the years have been following developments in this area will note that these findings are not new and can be traced back to the early 1990s. For example, of the 17 issues highlighted above, nine (53%) were a repetition of those contained in the PAC’s 2010-2011 report; six (35%) in its 2009 report; and eight (47%) in the 2007-2008 report. Who is to blame?

The Way Forward

Given that the PAC is not a full-time body, and considering the above observations, it is evident that the PAC is not equipped to deliver on its mandate to hold the Government accountable for its stewardship and accountability responsibilities. We reiterate our previously stated suggestion that the National Assembly adopts the United Nations model whereby an independent committee of experts: (i) meets immediately after the Auditor General issues his report to review the report; (ii) conducts hearings involving Heads of Budget Agencies and other concerned officials; and (iii) issues its own report to the PAC. This exercise should not take more than one month of full-time effort. The PAC then carries out its own examination over the next month using the committee of experts’ report as its main frame of reference, after which its issues its report to the National Assembly. In this way, the entire accountability cycle, including the issuing of the Treasury Memorandum, can be completed within 12 months of the close of the fiscal year.

This suggested approach will require a slight amendment to the Standing Orders of the Assembly, which should not be difficult to obtain if we are serious about the economic, efficient and effective use of public resources and assets as well as holding the Government to account for the discharge of its stewardship and accountability responsibilities.