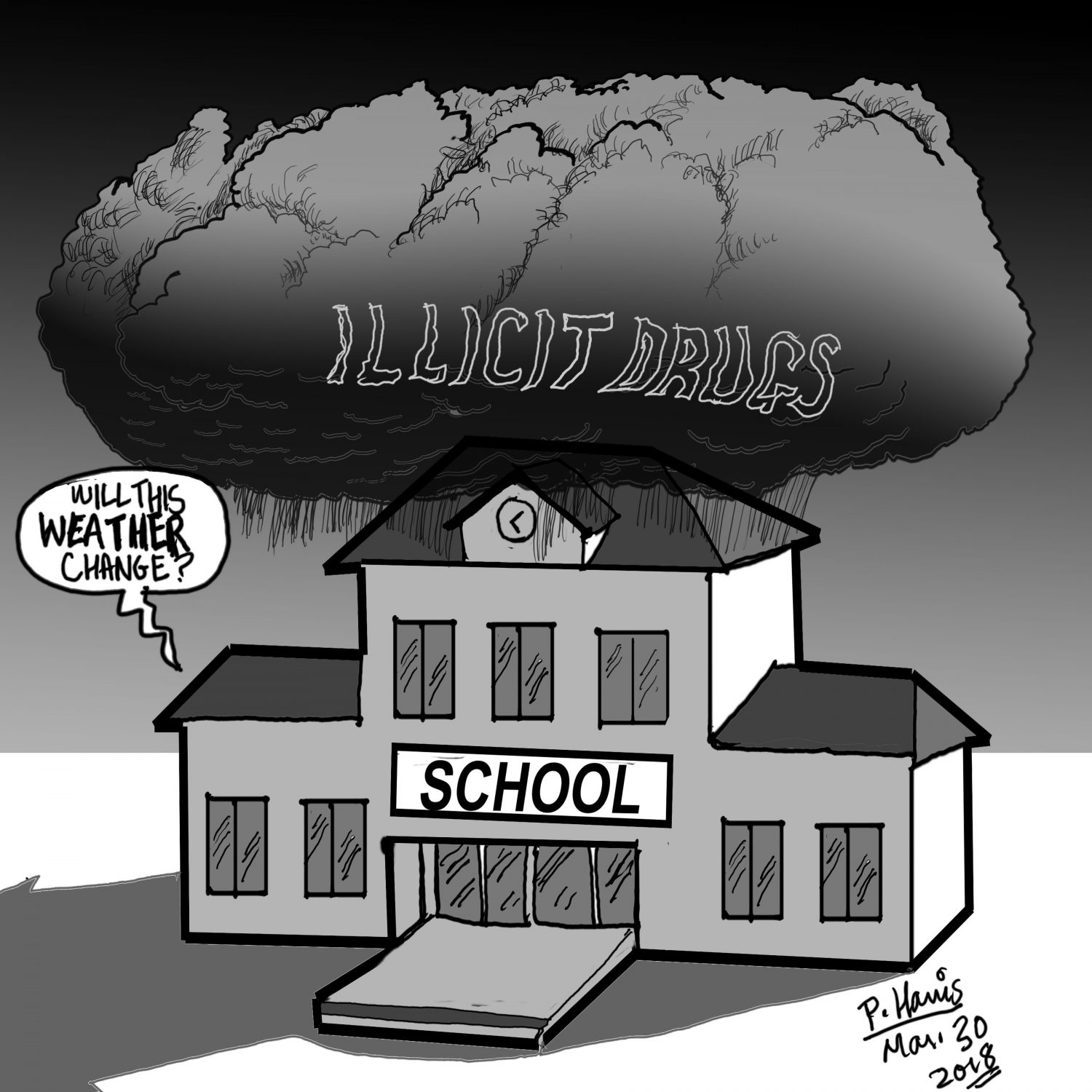

Hardly anyone batted an eyelid when the Stabroek News reported on February 16th last that the Customs Anti-Narcotics Unit of the Guyana Police Force has unearthed “a drug ring inside two Georgetown Secondary schools” and that following police investigations charges were expected to be laid “soon.”

This was by no means the first time that reports had surfaced regarding the pedaling and use of drugs in the school system in Guyana even though the customary absence of subsequent disclosure on these kinds of incidents by either the police or the Ministry of Education has means that details are usually few, particularly those that have to do with the responses of the authorities to these developments and such measures as being are put in place to attempt to respond to the challenge. The truth is that the Ministry of Education appears to favour a more-or-less ‘silent’ approach to problems of this kind, driven, it seems by a line of reasoning that if it remains quiet for long enough the problem will go away. That approach has not worked and it is high time that the Ministry wakes up to that reality.

Fortunately for concerned audiences, not least parents of school-age children, there are sources of information that can sometimes be no less reliable than those regarded as official ones. What, one suspects, is the posture of ‘discretion’ by the Ministry of Education, for example, is, in reality, a seeming lack of any structured awareness of the problem of the proliferation of drugs in schools and accordingly its inability to proffer any structured solution to the problem. The next best bet, therefore, has been to resort to the teachers who are not only located ‘in the belly of the beast,’ so to speak, but who are sometimes – on condition of anonymity – far more forthcoming in their ‘offerings’ on the problem.

Before addressing the issue of who is saying what about the problem, however, it would be instructive to examine why teachers, for example, are such a valued source of information. Insofar as the in-school welfare of children is concerned, teachers are the first line of defence against outside intrusion. It is their overall ‘policing’ role that plays the pivotal part in detecting deviant forms of behaviour that frequently provide telltale signs that something is amiss. Where drugs in schools is concerned, teachers are, unquestionably the watchdogs. Here, the bottom line is that the ostentatiously phrased circulars intended to serve as in-school guidelines can often lag so far behind rapidly unfolding realities that it is the real world, hands on experience of streetwise teachers that very often save the day.

One question that arises here is whether teachers have access to any kind of official training/orientation – perhaps through collaboration between the Ministry of Education and the Guyana Police Force – that properly equips them to detect possible drug distribution/drug use in schools. The answer, as far as the teachers themselves tell us is a resounding no. As one senior teacher at what is considered to be one of the leading secondary schools told the Guyana Review, “when you know the road you know what to look for,” an insinuation that the ‘education’ which teachers receive in how to detect drug pedaling and drug use in schools derives from sources other than the Ministry of Education.

The Guyana Review’s own probe found, as well, that while teachers acknowledge their ‘watchdog’ role, concern over likely ties between in-school drug pedaling and the wider criminal drug distribution network evoke concerns about their own safety so that, according to one teacher informant, “we are not as vigilant as we ought to be.” Long before the recent incident a female secondary school teacher had informed this publication that she had chosen to ignore activity among groups of schoolchildren which appeared to be linked to the distribution of marijuana in schools out of concern for her own physical safety.

A no less critical consideration in teacher attitudes to possible drug-related activity in schools is what we detected from our random interviews with teachers to be a breakdown in the relationship between the Ministry and its teachers. What we found was a significant number of instances of teachers who appear to confine their commitment to their classroom obligations so that they have come to consider much of what happens outside the classroom to be extraneous to their concern. When asked about the role of the teacher in addressing in-school drug challenges a senior mistress at a Secondary School told us that she considered drugs to be “police business.” Having contemplated her comment, however, the teacher, significantly, we thought, not only withdrew it but expressed the view that insofar as the relationship between the Ministry of Education and its teachers (over issues like pay, conditions of service and what they believe is insufficient respect for the role that teachers play) stays the way it is, teachers are, in many instances, likely to see that oversight role in looking out for in-school drug-related activity to be tantamount of being asked to ‘go the extra mile.’ “The reality is that they do not feel encouraged to go that extra mile,” our senior mistress told us.

While the Ministry of Education possesses what is known as a Safe Schools Protocol a small section of which addresses the issue of “Managing possession of weapons and illicit substances” and while it makes reference to a goal of “establishing a drug and contraband – free school environment” the document is verbose but yet at the same time decidedly vague on the issue of clear strategies for the realization of this goal. More significantly, its content appears not to be set against the backdrop of the complexities of the contemporary drug culture and contains no information regarding such serious and specific enforcement mechanisms as may be at the Ministry’s disposal to effectively enforce what it says is the “zero tolerance approach” that is has adopted in relation to drugs in schools and drug-use by schoolchildren.

Under its Safe Schools Protocol the Ministry of Education urges Heads of schools to make the most of the resources of the police in controlling weapons and illicit substances” and directs Headteachers “to take a zero tolerance approach to the possession of contraband items by students.” It further urges that possession of drugs “be reported to the Schools Welfare Unit, the police and the parents of defaulting students.” Further, Headteachers are “directed to notify all parents in writing of the school’s zero tolerance” of drug possession “and persuade them to “pay closer attention to the activities of their children.” The Ministry of Education may find it instructive to learn that the twenty (approximately) teachers from schools in Region Four with whom the Guyana Review spoke believe that the effective implementation of the Safe Schools Protocol cannot come about in the absence of the following:

1. Where there is a significant improvement in the general quality of the relationship between teachers and the Ministry of Education;

2. Where there exists a systematic and sustained drug-monitoring sensitization training programme for teachers in schools across the country;

3. Where there is much greater evidence of collaboration between the Ministry of Education (including teachers) and other stakeholder agencies viz. the Guyana Police Force, the Child Care and Welfare Authorities and other relevant public and private sector agencies in seeking to respond to the problem;;

4. Where there is a concerted effort to significantly strengthen the mechanism of the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) in order to facilitate more direct involvement by parents in responding to the problem.

Here, there is need to expand on the role of parents and communities in responding to the challenge of drug-pedaling and drug use in schools. Tragically, there is every likelihood that children often first encounter drugs in homes, family circles and in communities where they live. Here, one should add that the customary ghettoization phenomenon that commonly locates drug pedaling and drug use in poor communities is a considerable myth. Indeed, an examination of the reality of the presence of drugs in schools may well yield an entirely different reality.

Whether the Ministry of Education possesses the ‘human tools’ (inside the Ministry itself) necessary with which to plan and execute a regime for delivering a planned and sustained drug sensitization programme that impacts both teachers and children is unclear. What is clear, however, is the problem has long passed the point where the sort of placatory polemics to which the Ministry has customarily resorted will suffice.

Here, the point needs to be made that, not infrequently, parents and communities may have a bigger role to play in helping to respond to the problem than we think. There is every likelihood that children often first encounter drugs in homes, family circles and in communities where they live. Here, one should add that the culture of ghettoization that commonly locates drug pedaling and drug use in poor communities is a considerable myth. A careful examination of the reality of the presence of drugs in schools may well yield some surprising realities, not least, that so-called “better off” homes are not necessarily insulated from the influence of drugs.

The focus on drugs in coastal schools overlook what we are told is a more serious problem in hinterland communities which, given their proximity to our open borders, are vulnerable to drug-trafficking from neighboring countries. The Guyana Review has been told that there is a preponderance of marijuana cultivation in some hinterland regions (we were unable to determine which regions are the biggest marijuana growers) and that much of what is produced finds its way into the hands of school-age children.

No one is suggesting that the Ministry of Education does not already have its hands filled with a range of curriculum-delivery issues though it would be altogether counterproductive to ignore/overlook what would appear to have become an entrenched problem which can hopelessly compromise the Ministry’s substantive mission.