By Barrington Braithwaite

The city we know as Georgetown rose to prominence from the mud flats of the Demerara river, the deepest of the three prominent rivers of the colony of Guiana. In the 18th century, our town was born as a port town in the age of slavery and we have never quite reflected on its birth and rise and the decline of the pivotal working class population that sustained the restricted social masses from its birth as Stabroek, to its rebirth as old Georgetown. To have a more comprehensive understanding of this we must examine the phenomenon through the eyes of Henry Bolingbroke who wrote as he saw our capital town in 1799.

“Stabroek, the political metropolis, and principle seat of change for produce of all the countries adjacent to the Demerary and Essequibo, is situated on the eastside of the river Demerary: its site is low and level. It has an oblong form. The principle streets are quite straight, with carriage roads. The middle street, leading from the King’s Stelling is paved with bricks, and has lamps on each side: another public stelling, or wharf [besides several that are private] is kept purposely in order for landing and shipping goods. A navigable canal on each side of the town, which fills and empties with the tide, affords the same convenience to those houses which are not situated near the water side. The population in Stabroek consists of about fifteen hundred whites, two thousand free people of colour, and five thousand negroes.”

Bolingbroke continues in his narrative to indicate the living force of the Town as it is with the rise of most towns and cities throughout history, as centres of trade and commerce in his description of the wards of Robbstown and Newtown, as edited by Vincent Roth, Robbstown [ likely the adjoining streets to Robb Street proceeding to the Wharves,] Newtown being the area that now envelopes the America Street-East Coast car parks………….. to once more quote that which is more relevant to our narrative…“ on each side of this town, which was built by the British, are two canals, the banks of which when the tide is up, appear like so many wharves, completely strewed with English manufactured goods, in bales, casks, trunks or boxes. Here the spirit of business is perceptible: the negroes, clad with blue trousers and checked shirts, moving to and fro with alacrity, performing those offices, which a white man, here and there distributed, dressed in nankeen pantaloons and a fine calico shirt directs from under an umbrella.”

After emancipation and the advent of indentureship Stabroek, changed to Georgetown in 1812, remained the colony’s main port town, with the descendents of the freed slaves constituting the main group of the ‘Stevedore’ labour force. The Wards of old Georgetown Werk-en-Rust, Cummingsburg, Charlestown, Bourda, Albouystown, among others, had become congested centres of humanity. Henry Kirke, an experienced Magistrate and Sheriff of Demerara in the early nineteenth century commented on the living conditions of congested old Georgetown as follows: “Let anyone walk through the yards which lead out of lower Regent Street, Lombard Street and Leopold Street in Georgetown, and let him ask himself how he would expect law-abiding citizens to be raised therein.”

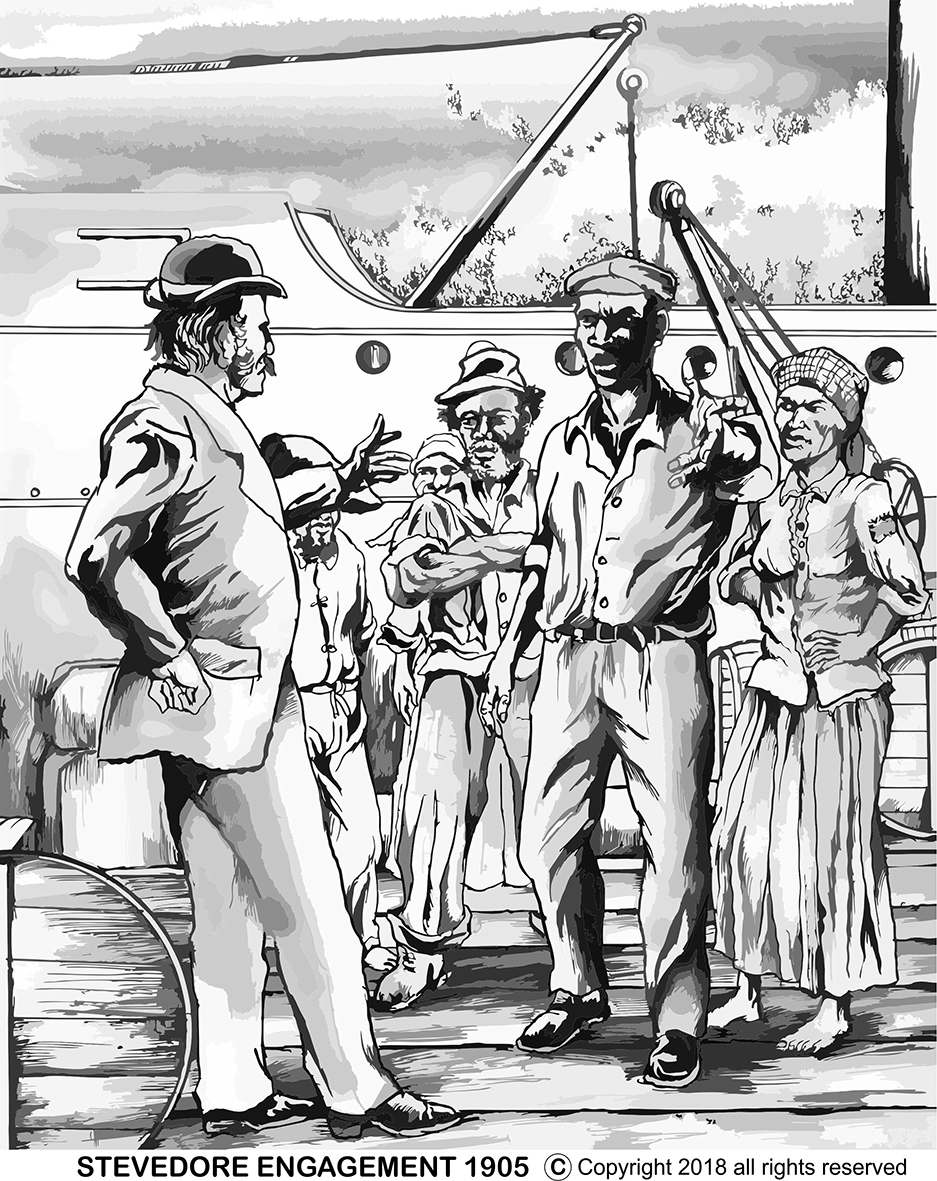

The water front, source of underpaid employment remained crucial for the sustenance of those very Wards with continuous protests. The riots of 1905 were focused on low wages and unemployment. A correspondent in the press indicated his awareness that the colonial authorities were not exercising any social responsibility. He stated: “I have often wondered at the supineness of the Government in permitting so many men to go on existing without any visible means on existence”(Walter Rodney: A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905.) The narrative indicated a method of waterfront employment that this writer still experienced in the mid 1970’s. “The casual or ‘outside’ labourer was poised uncertainly between unemployment and employment. Every day, large numbers of ‘outside’ labourers would assemble near the wharf gates and try to catch the eye of the wharfinger.”

This was the world that the stick fighter champion Hubert Nathaniel ‘Skibby’ Critchlow was born into. Afterwards, it became the source of his employment. Critchlow would challenge the hardships of the waterfront workers and launch British Guiana’s first political movement, the Guyana Labour Union in 1919. In those days, the state of wages was deplorable. In Themes in African-Guyanese History-Hazel M. Woolford relates an address by Critchlow on conditions on the water front that fuelled his courage to challenge the system- “Our working days were ten and a half hours. The system of a quarter day existed. There was no overtime for night work. We asked the employers to change those conditions. The reply was we must take them or go. I organized a strike on the water front in December 1905. Our claims were an increase in pay, which was very low. Truckers [called boys although adult men] made two shillings a day. They could scarcely get a whole day’s work, taking cargo to the barn.” Another reference lamented the general condition of the city (“the houses of the poor are ‘Dog Houses;) yet another expressed amazement at the capacity of labourers ”to do hard work from 6.00 am until noon, fortified merely by a cup of ‘sugar water and a few biscuits.”

Thus the struggle of the Stevedores, and of the masses of Georgetown was harsh and hopeless; yet they persisted and they struggled against the then mighty forces of commerce. With their victories, the Critchlow initiative proceeded to organise porters, railway workers, balata workers, miners, factory workers, sugar workers and extended their influence beyond the borders of Guyana, Critchlow was the epitome of the Stevedore and the West Indian Workers movement. Critchlow, doubtless, would grieve over what, today, are the remains of his legacy

In the years following Independence the wards of old Georgetown were still littered with congested living conditions, unemployment and a social class-caste system, inherited from the post emancipation era’s economic conflict between the freed African and the plantocracy and their new human tools. Burnham’s housing push, Festival City, South Georgetown, Roxanne Burhnam Gardens, Melanie Damishana, North Georgetown, the Stevedore Scheme…..collectively, brought relief to many. This was coupled with the launch of the Youth Corps and THE Guyana National Service, institutions designed to impart industrial and other skills training that were to make a significant social difference.

But the water front remained the bread and butter for the condensed population of South Georgetown and other wards of a growing Georgetown, the water front stretched from La Penitence wharf through Lombard Street to Kingston-GRB. It employed thousands daily, mostly in two shifts. It sustained great numbers of children bred in an environment that inhibited intellectual pursuit. Over time, that environment inculcated in them a sort of street cleverness; it also produced tough women, waterfront ‘lunch ladies’ no walkover when it came to protecting their modest enterprises; nor were the char women, cleaners and the women who stitched the bags at GRB. Many a son was negotiated into a job opening after the regulars had been employed. The water front offered employment across locations and jobs meant, as well, perks that had not been legally acquired………maybe a pair of sneakers or a pair of Clarks, arriving somewhere in Lodge or Ruimveldt, strapped beneath some stevedore’s baggy overalls [Farmer Browns].

The water front, like the sugar plantations, provided semi-skilled and skilled employment from the very beginnings of Guyana. I entered the waterfront after a life- shaping experience at the Kuru Kuru Collage…………. from being the Secretary of the Kuru Kuru Agro-Industrial Young Settlers Co-op Society [KAYS]. I committed two transgressions, the first was to sell our produce to independent clients who paid up promptly rather than to other cooperatives who were always behind in their payments. The other had to do with an altercation that I had had with another member and in which a weapon was involved. Though no one was seriously hurt my troubles began when her got to the Principal’s office first.

Changes in Merchant Marine shipping occurred in the early to mid-1980’s. A formidable source of employment abruptly [prior, in 1977 the suspected arson of GRB had wiped out hundreds of jobs] faded and with it the income that supported thousands of families in Georgetown especially. The commerce that they supported became considerably weakened. We were paid for the registered years we had worked, but a serious vacuum was created, nonetheless. Former supervisors became Security Guards, some turned to alcohol Those of us who were young enough turned to the military and the para-military. I tapped into my skills in to visual arts. The peculiar thing is that I have never read a line that exclusively chronicled the story of the stevedores. Perhaps this submission can mark the start of a more elaborate discourse on a segment of our history that is rich with colour and with significance. Even now, it is pleasing to reflect on the characters that shaped the waterfront, beyond ‘Skibby,’ larger than life charaters like Musha Parris, Auger Man, Lizard, Lemon, Belize, Fowler, men who held their own in an oppressive but important social environment. There were times when waterfront jobs were hard to come by and I applied to join the lower paid Port Police. Sgt. Barker was in charge of the Port Police in those days. He turned down my application. I recall his controlled outburst “I know you young man, once yuh work with them Stevedores yuh infected. Yuh want to now make booty legal?”