By Barrington Braithwaite

The city we know as Georgetown rose to prominence from the mud flats of the Demerara river, the deepest of the three prominent rivers of the colony of Guiana. In the 18th century, our town was born as a port town in the age of slavery and we have never quite reflected on its birth and rise and the decline of the pivotal working class population that sustained the restricted social masses from its birth as Stabroek, to its rebirth as old Georgetown. To have a more comprehensive understanding of this we must examine the phenomenon through the eyes of Henry Bolingbroke who wrote as he saw our capital town in 1799.

“Stabroek, the political metropolis, and principle seat of change for produce of all the countries adjacent to the Demerary and Essequibo, is situated on the eastside of the river Demerary: its site is low and level. It has an oblong form. The principle streets are quite straight, with carriage roads. The middle street, leading from the King’s Stelling is paved with bricks, and has lamps on each side: another public stelling, or wharf [besides several that are private] is kept purposely in order for landing and shipping goods. A navigable canal on each side of the town, which fills and empties with the tide, affords the same convenience to those houses which are not situated near the water side. The population in Stabroek consists of about fifteen hundred whites, two thousand free people of colour, and five thousand negroes.”

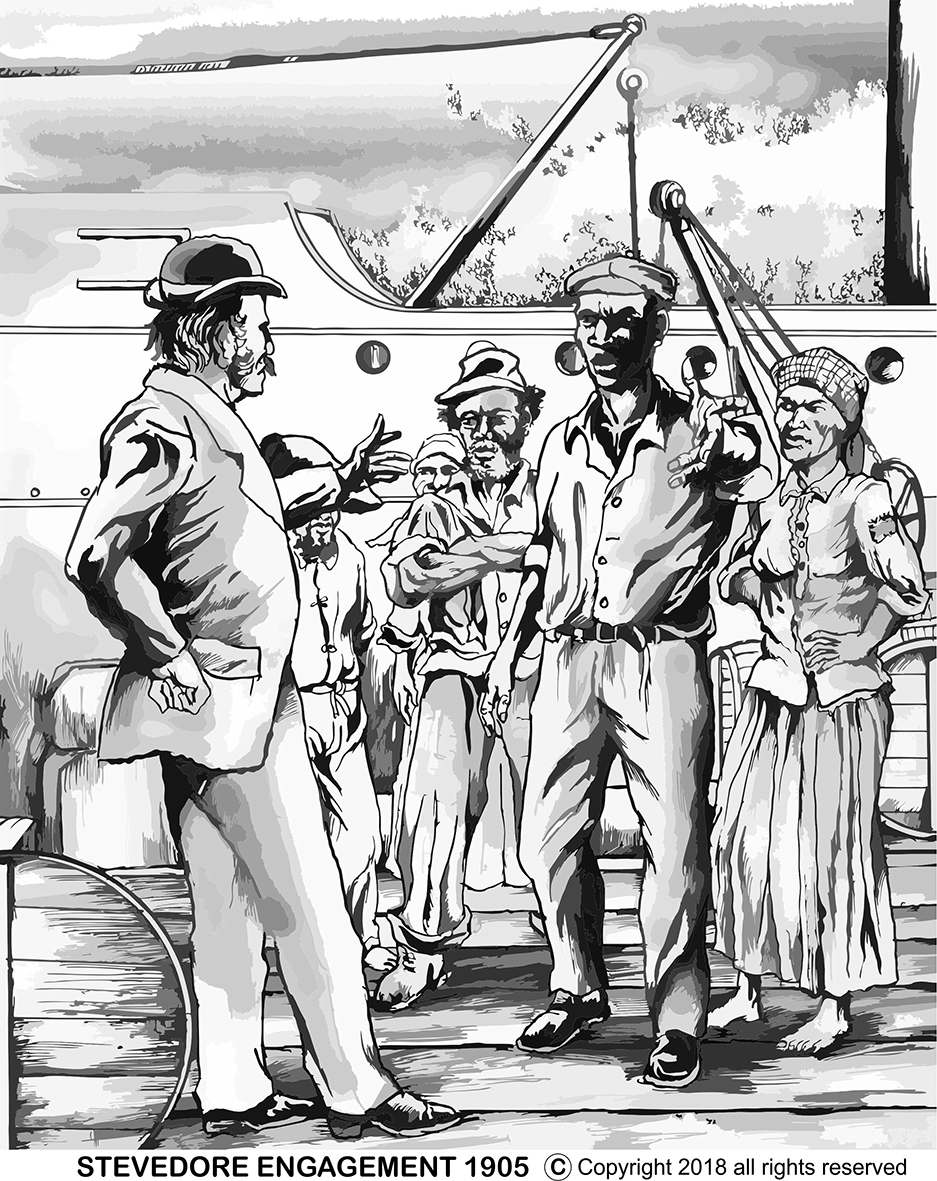

Bolingbroke continues in his narrative to indicate the living force of the Town as it is with the rise of most towns and cities throughout history, as centres of trade and commerce in his description of the wards of Robbstown and Newtown, as edited by Vincent Roth, Robbstown [ likely the adjoining streets to Robb Street proceeding to the Wharves,] Newtown being the area that now envelopes the America Street-East Coast car parks………….. to once more quote that which is more relevant to our narrative…“ on each side of this town, which was built by the British, are two canals, the banks of which when the tide is up, appear like so many wharves, completely strewed with English manufactured goods, in bales, casks, trunks or boxes. Here the spirit of business is perceptible: the negroes, clad with blue trousers and checked shirts, moving to and fro with alacrity, performing those offices, which a white man, here and there distributed, dressed in nankeen pantaloons and a fine calico shirt directs from under an umbrella.”