By Neil Genzlinger

Wilson Harris, a Guyanese novelist and essayist who addressed themes of colonialism and cultural identity in weaving stories of history, fantasy, myth and philosophy, died on March 8 in Chelmsford, England. He was 96.

His death was announced by his son Nigel Harris.

Mr. Harris, who had lived in England for almost 60 years, was one of the leading intellectuals to come out of Guyana, a small country on the northern coast of South America. His background was unusual for a writer: He had been a land surveyor for almost 15 years. But that work, which involved trips into Guyana’s jungles and vast savanna and contact with its diverse populations, turned out to be excellent preparation for a literary career.

Al Creighton wrote in a review in The Independent of London in 1993 that Mr. Harris’s works “are products of profound relationships with Guyana’s Amazonian landscape and with ancient Amerindian and European myths, the classics and Continental philosophy.”

As Mr. Harris himself put it in a 1992 interview with Project Muse: “The rain forest made an enormous impact on me. I learned that one should not attempt to — indeed one cannot — colonize the unconscious.”

Theodore Wilson Harris was born on March 24, 1921, in New Amsterdam, in what was then a British colony. Though the colony had significant poverty, his parents were middle class. His father, Theodore, was an insurer and underwriter. His mother was the former Millicent Glasford.

Wilson attended Queen’s College, a prestigious secondary school in Georgetown, in the mid-1930s, then studied surveying, passing the surveying examination in 1942. He then joined a government surveying expedition into the Cuyuni River area in the north of Guyana, toward the border with Venezuela.

“This expedition was a revelation for me,” he told Bomb Magazine in 2003. “Multitudinous forests I had never seen before, the whisper or sigh of a tree with a tone or rhythm I had never known.”

The experience influenced the poetry he would soon begin writing, as well as his first novel, “Palace of the Peacock,” published in 1960, the year after he relocated to England. Rich in symbolism, that book, about a multiracial crew that ventures into the interior of Guyana, is sometimes compared to Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.” It was part of a grouping of Mr. Harris’s works that became known as the Guyana Quartet.

Mr. Harris wrote 26 novels in all. He is generally included among a group of Caribbean writers (Guyana is often considered a Caribbean country because of its demographics and history) who explored themes of identity, colonialism, myth and more in lyrical, far-ranging prose.

“Harris, who is of mixed African, Scottish, Amerindian and possibly East Indian ancestries, and from a region that is a cultural confluence of four continents, is a believer in what he calls ‘cross-culturality,’ ” the literary critic Maya Jaggi wrote of him in 2006. Mr. Harris explained his idea of cross-culturality this way:

“It means one faction of humanity discovers itself in another; not losing its culture, but deepening itself. One culture gains from another; both sides benefit from opening themselves to a new universe.”

His novels were sometimes described as difficult, eschewing conventional plotting in favor of multiple narrators, intermingling viewpoints, jumps in time and a free-form prose that demanded concentration of the reader.

“I know that the view of science tends to be that we are all genetically coded,” he told Bomb by way of explaining his approach, “but I would suggest interior lives that touch nature and make us into living sculptures. Freedom therefore needs to be explored in depths beyond conventional linearities.”

He maintained that experimental approach even when taking up the poisoning of more than 900 cult members in 1978 at Jonestown, a settlement in Guyana. In “Jonestown” (1996) he addressed that horrific incident through a narrator named Francisco Bone, who slides out of reality and wanders across history and cultures as he explores the implications of the real-life event.

“There is something mechanical,” Kenan Malik wrote in a review in The Independent, “about the deliberate attempts to push the narrative to the edge of incomprehension — the story will be ‘bewildering to the Western mind,’ warns Bone — which diminishes Harris’s ability to wring meaning from the clashes of times and cultures that he sets up.”

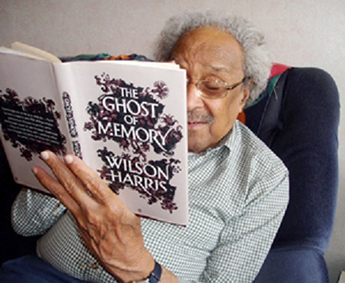

His other books included “Resurrection at Sorrow Hill” (1993), “The Dark Jester” (2001) and “The Ghost of Memory” (2006). He was knighted in 2010.

Mr. Harris’s wife, Margaret, died in 2010. In addition to his son Nigel, his survivors include three other children, Michael, Alexis and Denise Harris; six grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren.

At a forum in 2014 commemorating Mr. Harris, various speakers took up the question of how best to approach his challenging work. The Caribbean-born poet Ian McDonald described how Mr. Harris would read his early material. Mr. Harris, he said, would get louder and more enthusiastic as he went along, reaching the point where he would start hitting those nearby for emphasis.

“And then at the end he’d say, ‘You see?’ ” Mr. McDonald said. “And I’d say, ‘Wilson, I’m not sure I see, but I certainly feel.’ ”

Reprinted from the New York Times

MARCH 16, 2018