Part III

Born to lead

……………………………..

Friday, 23rd, March, 1962, West Indies v India, Third Test, Kensington Oval, Barbados

Frank Worrell, the West Indies Captain and his Indian counterpart, the Ninth Nawab of Pataudi strode down the steps of the Pickwick Pavilion, and headed out on to the pitch to spin the toss. Worrell spun a coin into the high Barbadian sun, and the Nawab made the wrong call. The Nawab of Pataudi Jr, as recorded in the scorecard, at the age of 21 years and 77 days, had become the youngest ever Test captain.

Ten years prior, to the day, the two captains had been ship mates on one of the famous ‘Strata’ boats of the P&O line, making their way to England. While the rest of the West Indies team headed home following the 1951-52 tour of Australia and New Zealand, the professionals – Roy Marshall, Sonny Ramadhin, Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes, and Worrell – were off to ply their trade in the Lancashire Leagues. When the boat docked in Bombay, among the passengers embarking were Vinoo Mankad, also bound for the Leagues, and the young Nawab headed to prep school in England. The latter soon became a regular attendee at the tennis ball cricket net sessions held on deck by the professional cricketers.

Now, the Nawab was captain of an Indian team in complete disarray. The previous Saturday had been marred by the horrifying incident of India’s Captain Nari Contractor being struck on the head by a bumper from Charlie Griffith in the territorial match against Barbados. Distracted by someone opening a window in the dressing room, (there was no sightscreen at the time), Contractor lost track of the ball, and suffered a fractured skull. Now, he lay in hospital, two operations later, having suffered the loss of a lot of blood and fighting for his life.

The Nawab, despite being the third youngest member of the tour party, and having only made his Test debut the previous December, had been appointed as Contractor’s understudy. Troubled by muscle problems, he hadn’t played in the first two Test matches which India had lost by ten wickets, and an innings and 18 runs, respectively, and his contribution in the innings defeat by Barbados, had been a pair of ducks.

The demoralized Indian team lost the Third Test by an innings and 30 runs, with the Nawab contributing 48 and another duck, while batting sixth in the order. The West Indies went on to sweep the series as they took the next two Test matches by seven wickets, and 123 runs, respectively.

It was a ‘sadder and wiser’ Indian captain who returned to India in April. The Indians were a battered lot, whose ground fielding had been poor, with many catches being spilled, and whose weakness against faster bowling had been exposed. Their tentative approach to the game was there for all to view. Their scoring was slow and their first instinct was safety first: play for a draw, rather than lose the game. Coupled with this malaise, fifteen years after Partition, was the fractious dressing room, comprising players from different regions and cultures, and where Marathi was often the dominant language, amongst several others. The Nawab, who had a fondness for bridge, had not been dealt a great hand.

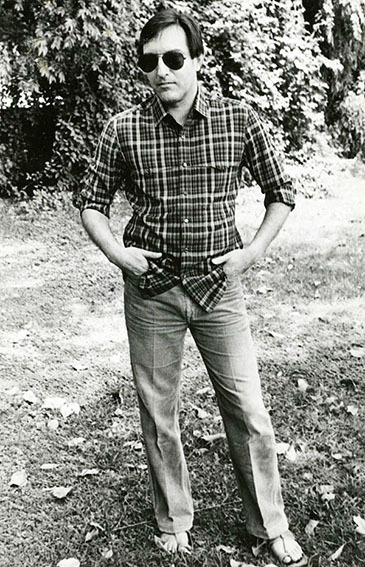

The Ninth Nawab of Pataudi was born and bred to lead, and lead he was going to do. No longer capable of fielding at slip, his first love, he set out to and became one of the best cover point fielders in the world. Relying on excellent anticipation, fleetness of foot and a quick release, the Nawab set the standard for the quality of fielding he expected at the Test level. The accident limited his ability to throw properly for two years, yet he developed to such an extent, that he drew comparisons to the South African Colin Bland, arguably the world’s best fieldsman in the 1960s. Bland, in an interview, once rated the Nawab, ahead of his fellow countryman, Jonty Rhodes (oft considered the world’s best fieldsman in the ʼ90s) because “his anticipation was so good, he never got his trousers dirty by diving around.”

Indian pitches at the time were not conducive to producing fast bowlers, despite the Indian captain’s criticism of them, so they would have to play to their strength, spin bowling. The fabulous Indian spinners, Erapalli Prasanna, Bishan Singh Bedi, Bhagwat Chandrasekhar and Srinivas Venkataraghavan were promoted under his guidance, as India, against convention, more often than not, took the field with three of them in the side. Inspired by his high standards, India developed a ring of sharp close catching fieldsmen, Ajit Wadekar, Venkataraghavan, Eknath Solkar and Abid Ali, who would snap up anything that uncertain batsmen failed to keep down from the quartet who tantalized many a team.

The conservative approach of playing for a draw was no longer an option. India was going to play to win every Test match and every series, both at home and abroad. So what if they lost? The Nawab, leading from the front, was going to attack the bowling. The lofted drive, (the hook shot had to be discarded), pulls, and drives were all parts of his repertoire, and he was going to play them come what may. Perhaps his luxurious upbringing and having been educated in England from the age of eleven, Tiger, as he was called in the palace as a kid, refused to be intimidated by the other cricketing nations or by the former colonial masters.

Quite often the Nawab’s innate leadership was displayed away from the eyes of the world. In the words of Bedi, a Sikh from a minority group, “Tiger was the first Indian captain who brought the culture of ‘Indian-ness’ to the dressing room. ‘Listen fellas, we are not playing for Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai, Bengal, or Maharashtra. We are playing for India. Think India, for goodness sake…’ These words sounded so good to the ears of a novice from Amritsar…”

Think India

Progress was slow. Change of a cultural mindset does not occur overnight. England’s visit to the sun-continent in the winter of 1963-64 resulted in five drawn Test matches, with the Nawab carving out an unbeaten double century, 203, in the second innings of the Fourth Test at Delhi. His innings lasted for over seven hours, inclusive of 23 boundaries and two sixes.

The Australians paid a visit in late ’64. The Nawab emulated his father, and Princes Ranjisinhji and Duleepsinjhi, with a century on his first Test appearance against the Australians. Batting sixth in the order, Tiger led India’s recovery from 76 for 5 to 276, in reply to the visitors’ 211. His 128 not out included 17 fours, but it was not enough to prevent a 139 run defeat, as the Australians accumulated 397 in their second knock. In the Second Test, Tiger with knocks of 86 and 53 inspired India to a sensational victory by two wickets, to level the series. Rain on the last two days of the Third Test ensured that India drew a series with the Australians for the first time.

Soon after, in early ’65, the New Zealanders arrived for four Test matches. In the Second Test at Kolkata, New Zealand put an intimidating first innings total of 462 for 9. Pat, as most of his team mates referred to him, led the reply with an innings of 153, inclusive of 29 boundaries, as India drew the contest. In the Third Test at Mumbai, India were dismissed for 88 in their first innings, fought back to declare their second innings at 463/5. New Zealand held on for a draw, as the four day Test finished with the Kiwis perilously placed at 80/8. The Nawab hit his fourth Test century, 113, inclusive of 17 boundaries and two sixes, as India accumulated 465/8, in their first knock in the Fourth Test, on the way to a seven wicket victory and a one nil series win. India’s cricket was on the rise.

Garry Sobers’ all conquering West Indians arrived in 1966-67 and provided a reality check, taking the three match series 2 – 0. Later that summer, the Nawab, led India to his second home, England. In the First Test at Leeds, India found themselves against the ropes early on the third day. England had compiled 550 for 4 declared, and in reply, India had capitulated for 164, with only Engineer, 42, number nine, Surti, 22 and Pataudi, last man out, 64, getting to double figures.

“Then, at Headingley in the first Test, last summer, he played his epic innings of 148 which lifted India out of the dark pit of despair. India lost in spite of his courageous effort, but in defeat they took away as much honours as the winners,” from the 1968 Wisden Cricketers Almanack, which selected him as one of the Five Cricketers of the Year, an honour also bestowed on his father, in 1932.

England swept the series 3-0, as did the next hosts, the Australians, the following winter. The Indians then flew across the Tasman Sea for four Test matches in New Zealand, their fourth series in fourteen months. Another defeat loomed. Against all odds, Pataudi’s spinners and Ajit Wadekar’s batting, led the visitors to a surprising 3-1 victory. It was first time India had won a series abroad.

In the autumn of 1969, the Kiwis paid a return visit and held the hosts to a 1-1 draw in a three match series. Bill Lawry’s tough Australians followed immediately afterwards and inflicted a 3-1 defeat. The Nawab was having a hard time cultivating the positive mindset which he desired for the team.

1971

On the 8th January, the Indian selectors met at the famous Brabourne Stadium in Mumbai to select the Indian captain for the upcoming tour of the West Indies. Bal Dani had proposed replacing Pataudi after 36 Tests in charge, but M Dutta Ray, C D Gopinath and M M Jagdale were in favour of retaining him. The Chairman of the selectors, Vijay Merchant favoured Wadekar as the new skipper. Unfortunately for Pataudi, Dutta Ray missed the vital meeting, and with the vote tied at 2-2, Merchant used his casting vote to ensure that Wadekar was appointed the captain. In some quarters, Merchant’s action was viewed as the settling of an old score when he had been overlooked for the captaincy of India’s 1946 tour of England. The honour of being India’s third captain had been bestowed on the Eighth Nawab of Pataudi.

Pataudi immediately announced his unavailability for the tour and his entry into politics.

Following her landslide victory in the March 1971 general elections, India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, having previously failed to get the Indian Parliament and the Judiciary to agree with her demand to abolish the Privy Purse, announced the 26th Amendment to India’s Constitution. The act meant that all the Princes were relieved of their titles and the culmination of the Privy Purse.

Views on this sensitive subject have ranged far and wide. One trend of thought was that Indira Gandhi acted in bad faith and had broken her father’s promises to the former royal families (who had agreed to merge with India on the attainment of independence) because they had joined the Swatantra Party and had defeated many of the candidates of her Congress Party in the 1967 elections.

The Ninth Nawab of Pataudi, his personal rights, privileges and dignities stripped, was now Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi.

His short flirtation with politics ended in disaster with his opponent receiving 95 per cent of the vote. How much worse could it get?

In 1971, Ajit Wadekar’s team, including for the first time, the young opener, Sunny Gavaskar shocked the cricketing world. First, they defeated the West Indies 1-0 in the five Test series. A few months later, they repeated the trick in a three match encounter in England. India was sitting at the top of the modern cricketing world.

The architect, Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi was nowhere in sight.

Notes from a charmed life

In 1963, the Noob returned to Oxford and was reappointed captain. He also represented the university at hockey and billiards.

……………

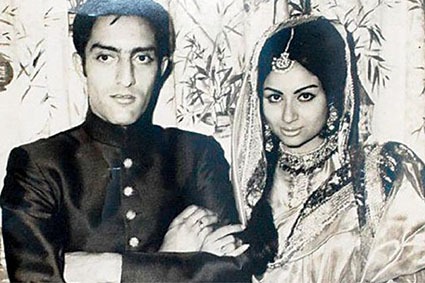

After a proposal on the streets of Paris, following a four year courtship, the charming Prince, the Ninth Nawab of Pataudi married the dashing Indian film star, a rare beauty, Sharmila Tagore on the 27th December, 1969. It was the first major union of Bollywood and international cricket and neither party received the blessings of their respective families. She was a Hindu from Bengal, he was Muslim. Many observers had obviously overlooked the Nawab’s habit of going against the grain. The marriage defied the odds, and produced three children, Soha Ali Khan, Saif Ali Khan and Saba Ali Khan, the first two following in their mother’s path to Bollywood.

…………………

MAK Pataudi was reappointed to lead India for the 1974-75 home series against the West Indies. He missed the second Test with an injury, and returned with India down 0-2. Pataudi and his trusted spinners led India to successive wins, to tie the series 2-2, only to lose the final Test by 201 runs. His form with the bat, as in previous series with the Caribbean side, was poor. It was the last time the Nawab appeared in a Test match.

……..

Once questioned whether the 1983 World Cup victory was the turning point of Indian cricket, he replied, “No, I think what changed before the World Cup was getting colour television. And we also started getting Indian commentary that spread the game to the rest of the country. Before that it was limited to only English-speaking people. This really brought change to Indian cricket.”

…….

“In 2004 the Noob, as he always remained to his school contemporaries, was invited back to Winchester for the Ad Portas ceremony, in which distinguished old boys are honoured. In general those received are expected to declaim in Latin. Pataudi, while greatly touched, preferred to end his speech in Urdu” (The Daily Telegraph).

…………..

Here’s Australian Ian Chappell, a tough competitor who gave no quarter and asked none, reflecting on the Nawab, at the Raj Singh Dungarpur World Cricket Summit, in December, 2011.

Chappell recounted the remarkable knocks of 75 and 85 played by Pataudi against Australia while he was only “half-fit”.

“I happened to be on the other side when Tiger played in Melbourne (1967-68). He had missed the first Test at Adelaide due to a hamstring injury. He was still half-fit but chose to play given the form of Indian batting.

“With a one-eye handicap, an injured leg coupled with Melbourne weather amid overcast conditions and India struggling at 25-5, he played sitting on his good leg on the back foot. I still remember him playing two stunning shots off Garth McKenzie and David Renneberg both of whom could bowl very fast.

“There were five or six rain interruptions during the match and every time he walked out he came out with a new bat,” Chappell said.

Chappell explained how Pataudi candidly told him that he did not carry a cricket kit when asked about the “mystery” behind his changing bats.

“He told me that his bag for the tour included a sweater, a jumper, a pair of socks, sock wear and [he] didn’t have anything else,” Chappell said. The Nawab was just grabbing whichever bat was nearest the dressing room door. His curiosity piqued, he enquired about what he did for a living.

“I am a prince,” he replied, a concept Chappell was unfamiliar with, so he prodded the Nawab again, who, a bit exasperated, snapped, ‘Ian, I ‘m a bloody prince.’”

………………

Statistics cannot quantify the Nawab’s contribution to India and Indian cricket. Blessed with charmisa, a laissez-faire approach to life, a gift for leadership, and a sharp tactician’s mind, the Nawab was a visionary, a man ahead of his time.

………………………………

The Ninth Nawab of Pataudi passed away on the 22nd September, 2011 and was laid to rest at the place he regarded as home, Pataudi.