D. Alissa Trotz is editor of the

In the Diaspora Column

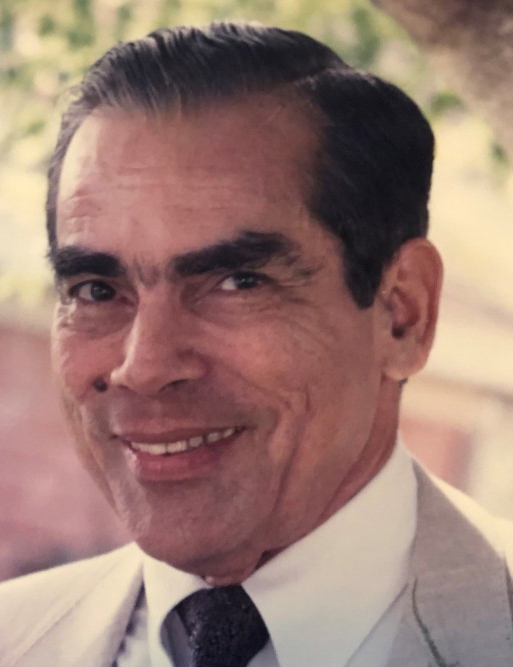

This Wednesday May 23rd, Professor Ivelaw Griffith, Vice-Chancellor and Principal of the University of Guyana (UG), will be hosting a solemn ceremony at the George Walcott Lecture Theatre in memory of Harold ‘Harry’ Drayton, who died in March of this year. Professor Drayton was the first deputy vice-chancellor and Vice Principal of UG, as well as Professor of Biology and Head of the Biology Department (1963-72). His family – his children, Richard and Alison, grandchildren and siblings – will be represented at the ceremony by his wife, Dr. Vonna Drayton.

Harold Drayton has gifted us with an extraordinary, 900 page autobiography, titled An Accidental Life, published by Hansib Books. Two weeks ago the Guyanese community turned out in their numbers for the most recent book launch in Toronto organized by the University of Guyana Alumni Association. Harold had been involved in planning the event, which turned into a celebration of his life.

The monograph spans some eight decades; Harry’s early years and education in Georgetown, Guyana; his teaching stint in Grenada; studying at the University College of the West Indies in Jamaica and then working there before leaving for Edinburgh where he would graduate with a doctorate; lecturing in Zoology in Ghana before taking up then Premier Cheddi Jagan’s invitation to return to Guyana and assume major responsibility for establishing the University of Guyana; moving to Barbados to take up an appointment with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO); and closing out a varied and illustrious career with his work at the World Health Organization at the University of Texas at Galveston.

The book stands as an incredible archive – offering ethnographic observations as well as first-hand accounts based on extraordinary recollection and detail of people, places and events

– in which the hopes of a decolonizing Caribbean generation and some of their postcolonial disappointments are contained within its covers. Barbadian writer George Lamming correctly described Drayton as a “witness and participant” who has provided us with an extraordinary “portrait of an era which defines the modern Caribbean and the long decisive process of decolonisation during the second half of the twentieth century.” So many of these portraits were deeply and simultaneously personal and political: from D, his beloved East Indian stepfather who would die just before Harry returned to lead the effort to create the University of Guyana; to Norma Meeks, a landlady who during a difficult period in Jamaica, demonstrated what caring labour could look like; to Richard ‘Dick’ Hart, whom he credits for his political education and after whom he named his son.

This book is really about education, not narrowly conceived in the book learning sense. The first lessons are those he learns from D, an autodidact with a fierce sense of justice who left school before he was 13. In an age before social media, Drayton describes scenes in which women and men gathered in D’s living room to read and argue “about contemporary local issues, unemployment; low prices being paid for ‘our’ sugar; increases in the price of food; Hubert Critchlow and the waterfront workers; A.A. Thorne and the Workers’ League that organised factory workers in the sugar industry; Ayube Edun, C.R. Jacob, and the M.P.C.A. – the sugar union for field and clerical workers.” Here we see a commitment to study, where study is defined as engagement and debate – frequently enlivened by food, laughter and quarrel – and is not confined to a restrictive notion of a classroom. They were connected via the sailors and dockworkers who brought news of the disturbances sweeping the English-speaking Caribbean in the 1930s. From the last ships that were repatriating Indians to India at the end of their indentured contracts, they followed the work of the Indian National Congress and opposed Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. Their sense of being Guyanese was not parochial and insular but internationalist and based on principles of solidarity and justice. For Drayton, it was, as Frank Birbalsingh has noted, driven by a “progressive, revolutionary, socialist ideology that inspired, for instance, his attendance at student festivals in Eastern European countries, and his seminal contribution to the establishment of the University of Guyana, the centre-piece of his achievement as a whole.” In Jamaica he was part of the People’s Educational Organization in Kingston, where there would be open meetings and public lectures attended by working class audiences on topics including apartheid, the Chinese Revolution, slave revolts, maroon wars, Jim Crow and racial discrimination in the US.

These commitments did not come without costs. Recipient of an elite education as he moved into Queen’s College, the country’s premier school for boys (at the time), one was meant to be prepped to take the reins as member of a suitably trained, respectable elite class that would not threaten the status quo. Even respectability was no guarantee; this was after all the same school that would initially deny Norman Cameron a teaching job because he was Black. The lesson would be clear when, as a member of the QC Literary and Debating Society, Drayton invited Jocelyn Hubbard of the Political Affairs Committee to come to speak with students about the political situation in British Guiana, only to be reprimanded by the Headmaster that “The British Govern-ment is spending one and three pence half penny on your education here, and you repay this by associating with elements and ideas subversive to the Crown.” Later, as a student in Jamaica, Drayton would be expelled from the University College of the West Indies, at the time on the official grounds of his involvement with a female student (Trinidadian Kathleen McCracken – they would go on to get married and have two children). As his son Richard Drayton recently noted, “as a result of the release of some of Britain’s secret colonial archives…my father was able to see a digest of the file which the Jamaica Special Branch had created on him since he was barely 20…All his life before this, he had only suspected that his politics were the main reason for his expulsion but had never had proof.” Among the files he would find the following reference to his time in Jamaica: “Subject came to security notice in December 1949 through his association with people of known left wing sympathies. In February 1951, during the course of labour disturbances among the workers employed by Higgs and Hill on the construction of the University College, DRAYTON and others were active in encouraging workers to prolong the strike. About March 1951 DRAYTON was expelled from the University College for receiving Communist literature and through his association with a female student….”. Later, at the University of Guyana, he would encounter challenges and roadblocks, including from those (in the PPP) who had originally invited him to return in the first place. Facing an increasingly hostile and repressive climate after the PNC came to power, he decamped to Barbados, where he would become a regional civil servant with PAHO.

In his commencement speech in 1974, six years after the first rigged elections that ushered in 22 years of dictatorship in Guyana, poet Martin Carter remarked: “It is precisely in times of crisis that we must re-examine our lives and bring to that re-examination contempt for the trivial, and respect of the riskers – those who take the risk of going forward boldly to participate in the building of a free community of valid persons…” Harold Drayton was such a risker, returning to Guyana in 1962 at the height of the country’s political crisis, to create a university from scratch (referred to derisively at the time as Cheddi’s night school). He has left us with a rich archive of institutional memory; he has written two diaspora columns for this newspaper on these early efforts; authored a chapter in book The University of Guyana – Perspectives on the Early History; and dedicated a great deal of his own autobiography to his administrative experiences. Bob Marley tells us to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery, and teachers like Guyanese historian Elsa Goveia centred Caribbean people in her classes, making us the subjects of our histories (Goveia taught at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica and had herself accepted an invitation by Professor Drayton to give lectures on Caribbean History for a newly inaugurated UG course before the idea was scrapped in 1964 on the altar of administrative politics and political expediency).

We are on the eve of Guyana’s 52nd independence anniversary. What is so remarkable about Drayton’s vision – especially today, when so much of the Caribbean has been more or less recolonized by the dictates of international financial institutions that the late economist Norman Girvan described us as In-Dependence not Independent – was his unwavering sense that decolonization was as much as a cultural and educational project as it was political, social and economic. We see this not just in what was proposed but the kinds of pedagogies that accompanied these efforts at curricular transformation: courses on World Civilization and Caribbean Studies that would be required for all faculties and also open to the general public (today we are back to fees and the idea of an open university seems a distant dream); courses on social biology that encompassed discussions of racial science and engaged head on the challenges of these legacies in Guyana and the Caribbean; first level mathematics courses for all science students; teachers – not all Guyanese or even Caribbean, but rather an internationalist crew – who came to join the faculty, driven by a commitment to social justice. This is radical literacy. Doing the work it takes to see ourselves. It takes careful labour, as Angela Davis has noted, to “base your identity on your politics, rather than your politics on your identity.”

Three years ago, in an email exchange on the future of Guyana and just on the eve of the last general elections, Harry wrote to me: “When in August 2009 I reached my 80th birthday, I decided that one of my 21st Century decisions should be: to eschew partisan politics in my homeland , if only because I had by then been living outside of Guyana – except for short visits -, for nearly 40 years, in the course of which, despite my best efforts, I had become increasingly unaware of the changing social and political landscape with which I had been so intimately associated in the 60’s and early 70’s. Another important reason for my major decision had been, and is, my firm belief that the younger generation of “actors” in Guyana must assume full responsibility for all the fundamental decisions as to the kind of Guyana and national institutions they wished to live in, and to aspire to achieving. Persons of my generation should be content with reflecting on, and chronicling as best we can- both orally and in writing – the problems with which we were confronted in bygone years, the plans that were made (those that went awry and those that bore fruit); and responding to requests from younger people for advice on possible solutions to broad national issues, some of which have their analogs in countries all over the world.”

Harold Drayton also delivered his papers – about 13 boxes – to the National Archives in late 2013. He has more than fulfilled his promise to leave a reflective trace – tracks for new generations to explore, follow, deepen and extend. As we honour his contributions at the University of Guyana this Wednesday, we also thank his family for sharing him with us.