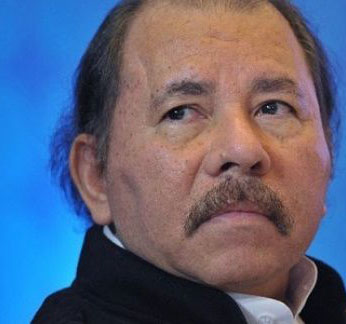

MANAGUA, (Reuters) – A thuggish response to weeks of protests has eroded carefully constructed pillars of support in the Church, military and business world for Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, emboldening calls for the ouster of the former Marxist guerrilla who has dominated politics for decades.

More than a month after changes to the Central American nation’s social security system triggered student-led protests, indignation at a brutal crackdown in which at least 77 people have been killed and over 800 wounded has morphed into a daily challenge to Ortega’s rule.

Protesters demand he step down, while regional diplomatic body the Organization of American States said last week he should hold early elections. He has as yet shown no sign of heeding that call, which could end one of the longest standing leftist governments in Latin America, a staunch ally for socialist Venezuela.

It will be not easy for the loose alliance of students, farmers, politicians and academics to dislodge Ortega, 72, who was re-elected in 2016 with nearly three-quarter of the votes after limiting opposition participation.

But the Sandinista leader, whose office acknowledged a request for comment on this story but provided no immediate response, looks more isolated and fragile than at any other time in his current 11-year tenure as president.

Support from the Catholic Church and the private sector is wavering. There is visible discomfort in the military, a solidly Sandinista organization constructed by Ortega’s brother from the original rebel army that overthrew a U.S.-backed dictator in the 1970s.

Even though the government backpedaled on the social security measures after five days, pent-up discontent exploded.

“This is a civic revolution, unprecedented in my country,” said Violeta Granera, a sociologist who ran as an opposition vice presidential candidate against Ortega in 2016.

The protests, she said, were nothing less than “a national demand for a total change in the economic, political and social system.”

The latest sign of fracturing came on Wednesday, when after just four days of talks, Nicaragua’s Episcopal Council of Catholic bishops suspended a “national dialogue” that had widely been seen as a chance for Ortega to take the wind out of the protests by making small concessions.

The Church had fallen behind its former adversary when he embraced Christianity before his 2007 return to office as a more moderate figure who avoided hostilities with Washington and business leaders.

Yet, in a pointed assessment, Silvio Jose Baez, an auxiliary archbishop of Managua, said the government had failed to embrace the dialogue’s agenda of “democratization of the country.”

On Monday, a smaller group of government, private sector and church representatives restarted talks behind closed doors.

Students and government authorities agreed in the first days of talks to a truce that quickly fell apart when groups of youths attacked protesters entrenched at the Agrarian University of Nicaragua, badly wounding at least two people.

Dr. Carlos Tunnermann Bernheim, an education minister during Ortega’s first term as president in the 1980s and now a vocal critic participating in the talks, called the violence “a grave violation” of terms agreed in the talks.

Every day since, flag-bearing Nicaraguans have poured through cities and towns. Thousands took to the streets again on Saturday.

At night, protesters hunker behind barricades of brick pulled up from the streets or walls of chairs and desks on university campuses, bracing with homemade mortars for clashes with pro-Ortega gangs whom witnesses and rights groups blame for many of the casualties.

PARALYSIS

Daily highway blockades have snarled transportation across the country, as students and farmers erect makeshift barricades to damage the economy and wear down the government. The government estimates the turmoil has cost the economy some $250 million.

Despite the losses, many in the private sector are openly backing protesters and demanding change, turning against Ortega after an uneasy alliance in recent years that has undergirded strong economic growth.

In its most explicit move yet, the Superior Council of Private Enterprise in Nicaragua, which represents the private sector, called Sunday on businesses to “join the clamor of mothers, grandmothers and wives who demand justice for the murder of their loved ones” in a march on Wednesday.

“Nobody expected this violence to be the way it was and we all find it disgusting,” said Mario Arana, a former central bank chief and analyst of the private sector.

Arana said that as it dawned on business leaders that police were shooting to maim or kill, with rubber bullets aimed directly at eyes, chests, and heads, or even with live ammunition, “then things began to change for everybody.”

Arana’s version of events chimes with the investigations of two local rights groups and a report from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which last Monday denounced grave violations of human rights characterized by the excessive force used by state security forces and armed third-parties during the protests.

Following the accusations that the initial police response was indiscriminate and disproportionate, agitators in civilian clothing are now behind much of the violence against protesters, observers say.

Ortega has publicly lamented the violence, saying that not only opponents, but also Sandinista supporters, bystanders and police have been killed.

Ortega has consolidated his rule by neutralizing and co-opting credible opposition and stalling the development of independent institutions. His wife, Rosario Murrillo, is vice president and widely seen as a power behind the throne.

But the mass mobilization has allowed politicians such as Granera to forge new alliances between civic and political groups, including her own Broad Front for Democracy, she and others said.

Building an effective anti-government coalition could prove difficult, however, said Eduardo Enriquez, editor of La Prensa newspaper, one of a handful of independent media outlets.

“The longer we don’t see results, people are going to start getting tired and disappointed,” he said. “And they have the force, the brute force. So we don’t want to lose the momentum.”

ARMY RELUCTANCE

Another base of Ortega’s support is the army. But in recent days it has signaled its refusal to appear in the streets.

Privately to business leaders and then in a statement through a spokesman, senior commanders called for dialogue and said they would not repress the population.

Former officers in mid-May held a meeting in the town of Masaya, southeast of Managua, a former seat of the insurrection in the 1970s against then-strongman Anastasio Somoza and site of some of the most brutal clashes of recent weeks.

They spoke to a raucous gathering of protesters, beside a group painting a sidewalk tribute to the recently fallen, and a few feet from a makeshift hospital tent where volunteers treated wounded protesters who they, along with rights group and witnesses, said were denied access to government hospitals.

“All of us fought the overthrow of the dictatorship of Somoza. Then we participated in the defense of the revolution against the Contras,” said Carlo Breles, a former Sandinista commander. “Now we initiating a third struggle, against the dictatorship of Ortega-Murillo.”