![]() What is it that draws us to nature-based survival tales? Is it a weird sort of schadenfreude where we find it thrilling to watch someone we do not know experiences things we probably could not face? Is the appeal aspirational, where we would like to imagine that we could face the worst of tragedies and make it out alive? Is it that we find a sort of morbid fascination with seeing the worst things that Mother Nature can havoc? The new movie “Adrift” seems to fit certain prototypes, and then just as easily seems to disregard them. The most striking thing I thought as the credits began to roll, was how unexpected to find the entire thing so moving.

What is it that draws us to nature-based survival tales? Is it a weird sort of schadenfreude where we find it thrilling to watch someone we do not know experiences things we probably could not face? Is the appeal aspirational, where we would like to imagine that we could face the worst of tragedies and make it out alive? Is it that we find a sort of morbid fascination with seeing the worst things that Mother Nature can havoc? The new movie “Adrift” seems to fit certain prototypes, and then just as easily seems to disregard them. The most striking thing I thought as the credits began to roll, was how unexpected to find the entire thing so moving.

I had no plans to see the movie “Adrift”. I feel this confession essential to discussing the film. I turned up at the cinema to see another movie that was cancelled. So, I decided to be reckless and walked into the next film about to start, “Adrift.” The brief descriptions I found piqued my interest. A quick read seemed to place it in the context of last year’s nature based survival romance, “The Mountain Between Us,” with a little touch of the J.C. Chandor lost-at-sea drama “All Is Lost.” The two films could not be further apart, so I was curious to see where between them “Adrift” would fall. Its brief 97-minute run time solidified my decision to watch it. And, although the film makes good on a number of the films it can be classed with, it also deftly – strangely – rejects them just as often.

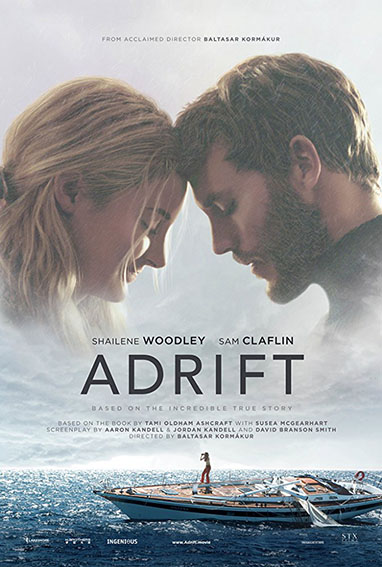

One might be tricked into thinking, at first, that there are two films within “Adrift”, and you would be forgiven for this because the duality of human nature and actual nature seems to be the central ethos of the film. “Adrift” is both a romantic drama and a survival drama. At first, it suggests that these two parts are separate. Related to each other, yes, but still disparate. The opening sequence leans into the survival drama aspect. It opens with an extended sequence of a ship wrecked by nature. Tami (Shailene Woodley) frantically makes her way through the wrecked yacht, looking for her lover, Richard (Sam Claflin), who is not on the yacht. She finds him floating, badly injured, a few feet from the boat, and in the middle of nowhere, with no land or ships in sight, is forced to save them both and get them to land. The film does not focus on moving forward from this moment of being caught adrift, though. Instead, director Baltasar Kormákur and his trio of writers opt to take us back to the beginning of their relationship to contextualise where they are now. This is not a mere flashback, though, but becomes part of the film’s consistent duality. There are two timelines at work here. As we watch Tami trying to save herself, and her man, we work our way through the romance between the two.

It’s an intriguing narrative decision. I’ll admit, the in medias res beginning made me cautious at first. “Adrift” ended up being one of three recent-ish films I saw that day that began in medias res and I was beginning to question whether there was a greater value to the conceit, rather than just a knee-jerk choice of filmmakers. The dual structure, though, becomes a surprisingly thoughtful narrative choice in a film that’s low on plot. In the past, we meet Tami, who is ‘spiritually adrift’ (I do appreciate puns as film titles). She is in the Pacific Islands for reasons she, and the audience, are uncertain of. She left a chaotic home environment to drift around the world and, as chance would have it, meets the similarly adrift Richard. They both seem lost in a way that’s more charming than annoying, and so naturally they gravitate to each other in a sort of dreamscape sort of Pacific romance. Two foreigners in a foreign land magically fall in love. Woodley and Claflin are an unusual couple. She seems like she’s from the seventies. He seems like he’s from the fifties. The most impressive thing about this portion of the film is the way the laidback charm of both portends a believable relationship. There is no great philosophical context to their courtship. However, the duo manage to effectively sell that weird sort of romantic film aspirational prettiness (sometimes him more than her) that movie magic depends on, through the requisite underwater kisses and picturesque dates.

The placid nature of their courtship becomes an essential balm for the chaotic nature of the narrative in the second timeline, where Tami tries frantically to navigate the perilous water with an

increasingly ill Richard. To accuse their romantic encounter of being banal would be to miss Kormákur’s clear intent to turn their romance into metaphor: Smooth sailing at first, but hit by stormy weather. The conceit and structure is incredibly simple, but there is an earnestness and decisiveness within the entire thing that makes it effective. And the cuts between the past and present adds an essential emotional core to the story, which becomes important later in the film when a key revelation is made, one that the film has been working to telegraph to us in some subtle ways from early on.

By the last moments of the film, with the requisite shots of the real-life Tami and Richard—the film is based on a true story—I was surprised at how invested as I was in this simple narrative. Like the storm that destroys the best laid plans of the couple at sea, “Adrift” sneaks up on you out of nowhere. Woodley has rightfully been earning plaudits for doing some incredible, emotive work. She’s excellent and the film is an excellent showcase for her but as the film’s climax came I realised the ostensible easiness of the romance building was more effective than it seemed. And that depends as much on Woodley’s strong work as it does on Claflin’s charming reticence. The film needs to convince us of the relationship at the centre to be effective even as the film is more than that. It’s a film about unlikely courage and fortitude when faced with the most bizarre of situations. The two timelines end up not being disparate parts of a whole but the same timeline, the love story IS the survival story and vice-versa. I suspect most will not know the true story it’s based on, or the resolution of it. I didn’t. And from the vocal response of the audience when they realised where it was all headed, they didn’t either. And, I think that’s the best way to approach “Adrift.” It makes its unlikely tale of human vs Mother Nature more effective for what we don’t know.

(Email your questions or comments to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com)