The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) yesterday upheld the constitutionality of Guyana’s presidential term limit and definitively closed the door on the possibility of a run for a third term by former president and current opposition leader Bharrat Jagdeo.

Overturning the decisions of the local High Court and the Appeal Court by a majority decision of 6 to 1, the Trinidad-based final court ruled that amendments effected to the Constitution prohibiting a president from serving more than two terms had been validly enacted.

“It was clear from the history of the amendments that they did not emerge from the desire of any political party to manipulate the candidacy for the presidency according to its agenda,” the court said in its ruling.

It added that democratic governance allows for, and indeed requires, reasonable restrictions to be placed on the qualifications to be a member of the National Assembly and hence also to be president.

The appeal was heard by Sir Dennis Byron, Justices Adrian Saunders, Jacob Wit, David Hayton, Maureen Rajnauth-Lee, Denys Barrow and Winston Anderson. Justice Anderson offered the dissenting opinion, in which he held that the amendments were unconstitutional because they disqualified five categories of persons from contesting for the presidency, without the approval of the people in a referendum.

In allowing the State’s appeal, the court, by a majority decision, set aside the orders of the local courts and declared that Section 2 of the Constitution (Amendment) (No 4) Act of 2000 was a constitutional amendment to Article 90 of the Constitution of Guyana, having been validly enacted.

The State appealed the decisions made by the local courts in favour of private citizen Cedric Richardson, who in the run-up to the 2015 general elections had challenged restrictions created by the amendments to Article 90 of the Constitution that were enacted in 2001 after the bipartisan Constitution reform process.

Richardson’s challenge argued that the amendment, which was passed by a two-thirds majority of all elected members of the National Assembly to effect the term-limit, “unconstitutionally curtails and restricts” his sovereign and democratic rights and freedom as a qualified elector “to elect the person of former president Bharrat Jagdeo” as executive president.

The amended Article 90 of the Constitution states at Clause 2(a) that a person elected as president after the year 2000 “is eligible for re-election only once” and at Clause (3) that a person who acceded to the presidency after the year 2000 and served therein on a single occasion for not less than such period as may be determined by the National Assembly “is eligible for election as president only once.”

Richardson contended that his right to choose whomsoever he wanted to be president, impliedly conferred by Articles 1 and 9 of the Constitution, had been diluted when Article 90 of the Constitution was amended.

Article 1 speaks to Guyana being an indivisible, secular, democratic sovereign state in the course of transition from capitalism to socialism. Article 9, meanwhile, provides, “sovereignty belong to the people, who exercise it through their representatives and the democratic organs established by or under this constitution.”

In July, 2015, the now retired Chief Justice (ag) Ian Chang had declared that the presidential term-limit was unconstitutional without the approval of the people through a referendum. In February, 2017, now retired Chancellor (ag) Carl Singh, and now retired Justice of Appeal B S Roy had dismissed the State’s appeal of Justice Chang’s ruling. Dissenting was then acting Chief Justice Yonette Cummings-Edwards, who held that the amendment did not diminish the democratic right of the electorate in electing a person of their choice as president.

The two courts concluded that an essential feature of a sovereign democratic state is the freedom which should be enjoyed by its people to choose whom they wish to represent them. They held that the amendment to Article 90 diluted the opportunity of the people of Guyana to elect a president of their own choice, which would have been inherently present in Articles 1 and 9. They further held that a referendum would be needed in order to make such an amendment.

However, Justice Cummings-Edwards found that Richardson failed to displace the presumption of constitutionality of the amendments by establishing that when Parliament purported to amend Article 90 it was acting either in bad faith or had misinterpreted the provisions of the Constitution.

In its appeal, the State relied heavily on her dissenting opinion. In a more than six-hour- long hearing before the CCJ on March 12th, attorneys for the State had argued that amendments to effect the presidential term limit were done in accordance with the Constitution, even as Trinidadian Senior Counsel Douglas Mendes, appearing for Richardson, maintained that the amendments could only be effected via a referendum.

Qualifications don’t diminish voter choice

The issues which had to be considered by the CCJ were whether Articles 1 and 9 of the Constitution could be altered by implication and, if so, whether their provisions had been changed or diluted by the amendments to Article 90.

The majority decision was embodied in the separate judgments of Justices Byron, Saunders and Wit.

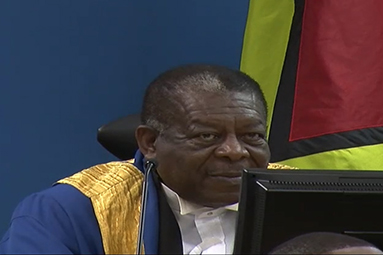

In a three-quarter hour summary of the judgment, which was delivered by outgoing president of the court Sir Dennis, it was noted that all the judges of the court agreed that Articles 1 and 9 could be altered by implication, but their views varied on whether there had been an implied alteration of the Articles.

Justice Byron began by outlining the three levels of entrenchment of provisions in the Constitution. The shallowest level, he said, allows for the alteration of certain provisions by an absolute majority of the National Assembly. He then moved to what he explained as being the intermediate level, which he said allows for the alteration of provisions, including Article 90, with at least a two-thirds majority vote of all members of the National Assembly. The third level, which he described as the deepest level, requires a referendum to alter provisions, such as Articles 1 and 9.

He said that only 10 Articles and four Schedules are subject to the deepest level of entrenchment, making it applicable only in exceptional circumstances, which go to the fundamentals of the State.

Sir Dennis said that the Constitution could have made the qualifications to be elected as president subject to the deepest level of entrenchment but, by providing different levels of entrenchment for Articles 1 and 9 on the one hand and Article 90 on the other, the inescapable conclusion was that the framers of the Constitution did not envisage that altering the qualifications for the presidency would necessarily impact on democracy or the sovereignty of the people in Guyana.

According to the judge, the proposition that altering the qualifications for president in Article 90 could require satisfaction of the procedure for altering Articles 1 and 9, which were entrenched at the deepest level, would itself change the structure of the Constitution.

This principle, he said, was borne out in the case of AG v McLeod [1984] 1 WLR 522, but he warned that the court would be astute in applying this principle to ensure that any such alterations fall properly within the category of qualifications for the position.

The court noted that the premise that Articles 1 and 9 implied an unlimited right to choose the Head of State was not obvious from the Articles and that the statements relied upon by the respondent from the case of Thornton and Powell to support such a view had been taken out of the context within which those statements were made.

Sir Dennis said, “The establishment of qualifications for the position of President, was normal in democratic Constitutions and does not necessarily diminish substantive voter choice.”

Additionally, having rebutted Mendes’ submission that the political theories of John Locke and American philosopher Johnathan Mansfield supported the view that a core feature of a democratic state was the unrestrained freedom to select a representative, Sir Dennis said that the concept of qualifications for office was not open ended and would include matters such as age, citizenship, residence and term limits.

In fact, he said that only these issues, excluding age, were addressed by the amendments in Guyana. Had there been attempts to introduce unusual

considerations to mask as qualifications the judge said that then different principles for adjudication would arise.

The CCJ president said it was clear from the history of the amendments that “they did not emerge from the desire of any political party to manipulate the candidacy for the presidency according to its agenda.”

He explained that it represented the considered opinion of the 1999 Constitutional Reform Commission after extensive national consultation of the national view on what was required to enhance democracy in Guyana, make the Constitution more relevant to the needs of citizens and reduce racial and political tensions in the country. He further noted that the amendments had national support. “The amendments were a single item of a whole suite of Constitutional amendments designed to reflect the evolving democracy in Guyana,” the judge declared.

Unsupported

The judgment also noted the views expressed by Justice Saunders, who said that Richardson’s suggestion that sovereignty meant that the people must be able freely to choose whomsoever they wish to govern them, and that prior to the amendment that was the case, was unsupported in constitutional theory and practice.

Democratic governance, he noted, allows for, and indeed requires, reasonable restrictions to be placed on the qualifications to be a member of the National Assembly and hence also to be president.

He observed that even before the amendments, Article 90 stated that a presidential candidate had to be qualified to be elected as a member of the National Assembly pursuant to Article 155, which stipulated a range of restrictions on who may be so qualified.

According to Justice Saunders, while it is true that Articles 1 and 9 do have “juridical relevance” and are not merely “idealistic references with cosmetic value only,” “they were not intended to confer individual rights,” but rather to guide governments, the courts, state and public bodies in the implementation of policy and the discharge of their functions.

It is against this background that he concluded Richardson was misguided in seeking to found his case on the breach of a right contained in Articles 1 and 9 that supposedly inures to him as an individual.

The judge said it cannot be the case that any and every new qualification or disqualification the National Assembly imposes on candidacy for public office automatically abridges democracy, nor does the removal of an existing qualification inevitably expand democracy.

He postulated that it would be quite remarkable if democracy or sovereignty could be measured in such a manner. “The status of Guyana as a sovereign and democratic state may be but is not necessarily implicated by an alteration of the qualifications established for election to the presidency,” he said.

Where the court is called upon to determine whether a particular amendment establishing new qualifications was within or outside the power of the National Assembly acting on its own without a referendum, Justice Saunders said that the court should consider a range of factors, including history, substance and practical consequences of the amendment, to the reasons advanced for it and to the interests it serves.

He said the court may also consider, albeit of lesser importance, whether it was passed by a bare two-thirds majority, with one-third of the members being vigorously opposed to it or whether it was instead passed unanimously.

Justice Saunders said the court was also entitled to look outside Guyana to other states within the Caribbean Community, all of whose members subscribe to the tenets of liberal democracy and assess whether the disputed Act was out of sync entirely with what obtains throughout the Community. The court may also look to the wider international community and draw on “the collective wisdom and experience of courts the world over.”

Transnational constitutionalism, he said, may provide guidance as to whether a particular constitutional amendment is abusive or consistent with what should obtain in a sovereign and democratic state. Ultimately, the court must ask itself whether the new qualifications are reasonably justifiable in a democratic society. “That is the litmus test,” the judge said.

Applying these principles to Richardson’s challenge, Justice Saunders concluded that the restrictions introduced by the amendment to Article 90 were found in many States that are liberal democracies. Where members of the National Assembly considered that term limits and the other amendments made to Article 90 did not dilute Article 1 or 9, he said the courts should look for some evidence to the contrary before concluding that such a view was wrong-headed.

“Where such evidence exists, courts will not shrink from deciding that the amendment is invalid unless affirmed by a referendum. But here, no such evidence whatsoever was put forward by Mr Richardson,” Justice Saunders declared.

With a focus on objective international standards of what a democratic state entails, Justice Wit noted that limits on re-election also pursued the aim of preserving democracy and protected the human right to political participation.

Citing international treaty provisions, jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and what he described as a very persuasive report on presidential term limits by the European Commission for Democracy through Law (the “Venice Commission”), Justice Wit concluded that according to the international standards, residence requirements are allowed provided they are reasonable.

Term limits, he added, contributed to guaranteeing that periodic elections were “genuine” and to ensuring that representatives are freely chosen and accountable. He said, “The introduction of term limits did therefore not dilute or water down the democratic status of Guyana.” He did say, however, that the restriction that only citizens by birth or parentage qualify for the presidency of Guyana would at first blush seem discriminatory or at least controversial but that this aspect of the case was never fully developed and so he did not give a definitive conclusion on that point.

Dissenting opinion

Meanwhile, in his dissenting judgment, Justice Anderson said that the crucial issue for decision was whether Articles 1 and 9 guaranteed to the people of Guyana the right to freely choose their president. He said that these provisions were akin to human rights provisions and are, therefore, to be given a generous, liberal and purposeful construction.

Article 154A of the Constitution confers upon the citizens of Guyana the human rights enshrined in the international treaties to which Guyana has acceded and which are set out in the Fourth Schedule.

These rights, he argued, must be respected and upheld by the executive, legislature and, very importantly, the judiciary. Among the treaties listed in the Fourth Schedule is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Article 25 of the Covenant affirms the right and opportunity of every citizen (a) to take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives; and (b) to vote and be elected at genuine periodic elections guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors. Similar expressions are to be found in Article 20 of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man 1948 and Article 23 of the American Convention on Human Rights 1969.

Having regard to these treaty provisions and the legal literature by Mansfield and Professor Simeon McIntosh as well as case law to which he referenced, Justice Anderson was of the view that the recognition in Articles 1 and 9 that sovereignty belongs to the people who exercise it through their representatives necessarily entails the corollary that the people are free to choose who their representatives will be, free, that is, from any constraints not imposed by the people themselves.

Justice Anderson advanced that in the sovereign democratic state of Guyana in which sovereignty belongs to the people, the people have supreme power or authority to govern themselves. This, he said, implies the right to self-determination, or as the Preamble to the Constitution states, it affirms the sovereignty and independence of the people. According to him, these pre-existing rights may be enlarged but cannot be constricted by the executive, legislative or judicial organs of the state, which derive their legitimacy from the sovereignty of the people as expressed in their Constitution.

He argued that there is an irrefutable presumption that the people know who would best represent their interests in government and are the ones to decide upon the suitability and categories of qualifications of persons to stand for office. He advanced that the imposition of restrictions that disqualify large numbers of persons from standing for election as president, which are not sanctioned by the people in the constitutionally-authorised manner, necessarily trenches on their freedom to choose their representatives and is concomitantly a fetter upon their sovereignty.

Justice Anderson went on to say that it may be true that certain modern notions are thought to be more conducive to democracy than older notions, but advanced that unless these notions have attained the status of jus cogens (the principles which form the norms of international law that cannot be set aside), they cannot be determinative.

According to him, it was not for the judges “to give effect to these modern notions by purporting to give an updated interpretation to the Constitution. The Constitution does not confer upon the judges a vague and general power to modernise it… the power to make a change is reserved to the people …, acting in accordance with the procedure for constitutional amendment. That is the democratic way to bring a Constitution up to date.”

In Justice Anderson’s opinion, the amendment was therefore unconstitutional because it disqualified five categories of persons from standing for the post of president who were not previously so disqualified without the approval of the people in a referendum.

For him, the question was not whether Guyana remained a democratic sovereign state, but rather, whether the amendments diminished or watered down the rights vested in the people as recognised in Articles 1 and 9. He was persuaded it did.

Although acknowledging that the amendments were the result of laudable efforts at political consensus and it was clearly inconvenient to strike down an important legislative fruit of the agreement that was reached on that occasion, Justice Anderson said that inconvenience was neither the test, nor an exception to the test, of the constitutional requirement.

He was of the view that “the Court was required to guard the constitutional requirement for the holding of the referendum as prescribed by the framers of the Constitution whatever the degree of inconvenience.”

Justice Anderson also did not accept that the delay of 14 years in bringing the constitutional motion was relevant on the facts of the action filed by Richardson. Whilst conceding that the length and nature of a delay could be such that no one had standing to challenge the constitutionality of an Act, he considered that as the matter of delay was not raised in the lower courts, it would be unfair for it now to be considered by the CCJ.

The court made no orders as to costs.

The state was represented by Attorney-General Basil Williams SC, Solicitor-General Kim Kyte-Thomas, Queen’s Counsel Hal Gollop and Ralph Thorne, Principal Legal Advisor Judy Stuart-Adonis and State Counsel Utieka John.

Richardson was represented by Senior Counsel Mendes, in association with attorneys Devesh Maharaj and Kandace Bharath.