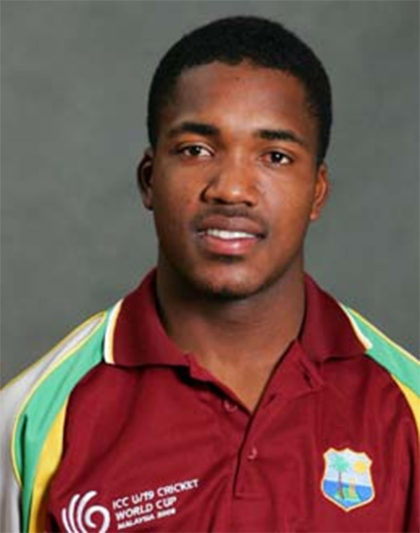

Devon Smith scored 7, 20, 61, 1, 2 and 0 on his comeback to test cricket. This testifies to his continued failure in international cricket and signals the retrogressive nature and underdevelopment of West Indies Cricket.

For years, West Indies have been known to select what locals call ‘players from the grave yard’ and Smith is no exception after his three-year absence from the side.

This would not be a normal circumstance around the world but, according to the late Tony Cozier, “applied to West Indies Cricket, normal is not an adjective that springs to mind.”

Similar decisions were made with the likes of Narsingh Deonarine, after four years, David Bernard, after six years, Kieran Powell and Devendra Bishoo, after three years and the list goes on. But these attempts have often not borne any rewards.

Despite being the leading run-getter in the Regional tournament, Smith has proven time and time again that he is not ready for international cricket.

Smith was dropped from the side after 2005, at that time a 23-year-old with room for improvement after scoring just one century and two fifties and on his return in 2007, he scored one 50 in 29 innings, by far a run too long.

Now at age 36, West Indies saw it fit to bring back an aging Smith, a slap in the face to the young vibrant talent looking to take West Indies into the next generation of cricket.

India, Australia, England and South Africa are testament to the changing of times with their leading batsmen and bowlers all under 30 years.

No other team in the world has shown such patience with players who have failed on the international scene but the West Indies.

According to Chairman of Selectors at the time of Jason Holder’s appointment to the captaincy, Clive Lloyd, “We expect him to be around for a very long time.”

At 36 years, how much cricket is left in Smith while the likes of 20-year-old Amir Jangoo, John Campbell (24 years), Tion Webster, Shane Moseley, Chandrapaul Hemraj (24 years), Shimron Hetmyer (22 years) and others are left by the wayside.

Also, if experience and chances become factors, out of favour, Leon Johnson was given nine matches to prove himself in tours against, at that time, the best in the world South Africa, India and Pakistan but while his average is better than Smith, he seems to be forgotten. Not to mention leading Guyana Jaguars to the title four successive years, a clear justification of his ability to read the game.

Similarly, Vishaul Singh was given six innings to prove himself but was only given the chance to represent West Indies at the age of 28 and after a few rough outcomes, he too was discarded.

Should Smith be given another run in the upcoming series against Bangladesh it will add evidence to the way West Indies have favoured certain players.

While Smith finishing the leading run scorer in the domestic tournament that should be used as a basis to merit the selection of players, it should be noted that Shivnarine Chanderpaul scored more runs than Smith in 2017 with an average of 62 with only Shai Hope averaging higher and the closest to him averaging 14 runs less but was never recalled. His international record speaks volumes as the second leading run scorer for the West Indies and his ever consistent form.

Former captain, Denesh Ramdin, who also averages higher than Smith in international cricket scored at an average of 61 with three centuries in the same series but was not selected while Smith walked into the West Indies side, leapfrogging those in line.

An exciting opener, Hemraj, who also made a huge impact in the four-day competition, was rewarded with an A team call up. Hemraj has been compared to the likes of Chris Gayle with his big hitting ability and at 24-years-old, is handy at the top of the order.

Hetmyer, who was deemed ill, is another young prospect who has shown his worth at the top of the order but should he recover it is puzzling to see if he would return to the side at the expense of Smith or will he have to toe the line and come through the ranks once more.

Even in the composition of the team, there was no need to break up the Kraigg Brathwaite-Kieran Powell partnership which, in the eyes of many was blossoming into a solid opening pair even prior to Powell’s self-inflicted exile. The recall of Smith also begs the question why does Darren Bravo continue to be left out of the side. With eight hundreds, 16 fifties and an average of 40, the Bravo fiasco has shown how thin skinned and divided players and administrators continue to be at the detriment of West Indies Cricket.

But the Dave Cameron-led board has always been one to make surprising decisions. The decision to drop two-time World Cup winning captain Darren Sammy on the basis that “he did not merit his spot in the team” was alright but to then appoint Carlos Brathwaite, who never captained before and only hit four sixes in the final of the 2016 World T20 was puzzling. Brathwaite has since spiralled downwards and it is baffling how he is able to make the side on merit.

Yet, the leading wicket-taker cannot merit selection in the test side.

Veerasammy Permaul finished with 50 wickets last season and continues to be overlooked. Imran Khan suffered the same fate in the 2017 season as well. According to Cameron, “No longer can we use the excuse that we do not have pool of talent in the region to compete in world cricket. Four years ago, we had just over 25 professional cricketers in the West Indies, and today, we have 177.

“What we have to do is to continue to upscale our cricketers, our management, our coaching staff and the administrative staff in order to produce world-class players. It continues to be a competitive environment for our players and there are times when decisions may not go your way.”

The obvious question to ask therefore is what does West Indies reward? Performance? Experience? Talent? Youth? Luck? Friends? or Favourites?

Your guess is as good as mine.