The basketball comedy Uncle Drew rests on the relationship between Lil Rey’s slightly overbearing coach, Dax, and the aging former streetball star, the eponymous Uncle Drew (played by current basketball star Kyrie Irving in heavy prosthetic makeup). The dynamic the two have is reminiscent of a well-worn one in situational comedies – especially black ones. There is the grouchy and somewhat irascible elderly man and the talkative, somewhat egotistical younger one. The roles depend on the young man thinking he knows everything there is to know about life, his intent on showing the old man all he does not know and, more often than not, him ultimately being proven wrong.

The basketball comedy Uncle Drew rests on the relationship between Lil Rey’s slightly overbearing coach, Dax, and the aging former streetball star, the eponymous Uncle Drew (played by current basketball star Kyrie Irving in heavy prosthetic makeup). The dynamic the two have is reminiscent of a well-worn one in situational comedies – especially black ones. There is the grouchy and somewhat irascible elderly man and the talkative, somewhat egotistical younger one. The roles depend on the young man thinking he knows everything there is to know about life, his intent on showing the old man all he does not know and, more often than not, him ultimately being proven wrong.

This dynamic has been a constant in black comedies, from Sanford and Son’s title duo to George Jefferson and his son Lionel, Cliff Huxtable and Theo and/or simultaneously Cliff and his father, Earle, to the relationships featured in both the “Friday” and “Barbershop” series. At its best, the dynamic offers something compelling about generation gaps and black masculinity across decades. At worst, well, at worst it infantilises young black American men in a country that already simultaneously infantilises them and villainises them. Presenting them as unable to be respectable enough to be taken seriously, but also too aimless in their ways to be valuable.

Uncle Drew isn’t really about black masculinity and the generation gap, but it isn’t NOT about that either, and it’s a particular part of it that’s been bugging me since I saw it. Uncle Drew thinks it’s about the power of sports and its ability to create family through teamwork–that’s what its final scene argues, and what director Charles Stone III and writer Jay Longino seem to want to say. Although it might be more accurate to say Uncle Drew is about the belief that if you try hard enough for something you will achieve it (a heart-warming but false premise). But, Uncle Drew isn’t really about anything because Uncle Drew is a 100-minute reel of film in search of a movie. Because, the movie we do have isn’t really about anything, at least not in the way it aims to be.

As the credits rolled on the basketball comedy to a small audience, laughing joyfully at the end credits, I admit my curmudgeonly reaction to the film made me balk slightly, and yet the paradoxical strangeness of this baffling film irked me the more I thought about it even as its very existence sets itself up as being an amiable and inoffensive thing.

Uncle Drew is based on a series of Pepsi Max ads that began in 2012. In the ads, Kyrie Irving plays Uncle Drew, a slightly cantankerous elderly streetball legend. Uncle Drew, the film, does not begin with the man of the title, but instead with Dax, a down-on-his-luck streetball coach struggling to take his team to the finals of the Rucker Classic. Although this premise suggests something more than a comedy sketch in search of a film, this premise is a trick because this premise remains a premise rather than a realisation for most of the film. Uncle Drew presents itself as a film with the parts of a clear plot. Dax has a long standing rivalry with the ingratiating Mookie (dating back to school days), a materialistic soon-to-be ex-girlfriend and a restless star player.

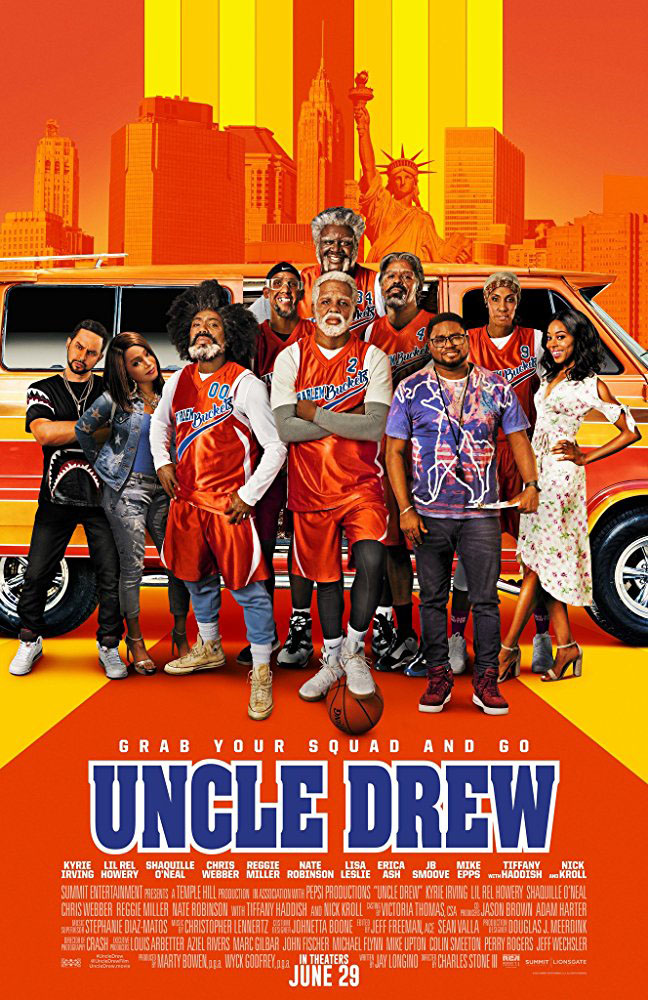

All these things come to a head when Dax’s investment in the Rucker Classic is blown when his team abandons him. All of these things set up the likelihood of real conflict but the film does not do anything with them. Plot is negligible for the first quarter because Uncle Drew is waiting for the eponymous Uncle Drew to arrive. We are waiting for the moment that down on his luck Dax meets the aging superstar Uncle Drew for the film to set up the inevitable “get the gang back together” party as Dax sets out to use a senior citizen team to win the $100,000 cash prize. There is a lot of set-up with no follow through as the film coasts from plot point to plot point, just to watch the men (Irving is joined by Chris Webber, Reggie Miller, Nate Robinson, and Shaquille O’Neill all in prosthetics) and lone woman (Lisa Leslie) play ball. And the games are shot well. But the movie around the game is all perfunctory and empty stuff that the film has no interest in on any plot level.

Uncle Drew means to be a warm and feel-good film but the thoughtlessness with which the film is put together betrays its intentions. It champions the old men of society as the ones who really know what’s happening, which is a tried trope and debilitating one of black men, especially in an America where they are under siege. Uncle Drew is made more ridiculous amidst the reality that its team of black men, and one black woman, are all played by younger persons masquerading as elderly characters. It’s a move that makes its initial message even hollower when given consideration. It’s hard to laugh at the film’s representation of women as either screeching harpies or docile supporters. The main rift of the film depends on two teammates torn asunder by the woman they both slept with. One marries her, the other mourns her for the rest of his life. Or so he claims. I’m not sure we ever learn her name. It’s all profoundly shallow. And I know that’s a paradox but that’s what this movie is.

As the film’s credits roll, we see bloopers of the cast flubbing their lines, and riffing on jokes from the film. It exudes more charm and ease than everything that comes before, which makes what we actually get that much more exasperating. In an early match, the elderly team play terribly. They all have talent but they’re not working in sync. That’s the film in a nutshell. No one here is an amateur, but when they are together the film is bafflingly inept.

(Email your questions, or comments, to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com.)

Uncle Drew is currently showing at Caribbean Cinemas and Princess Movie Theaters Guyana.