In the heart of Canal Number One, just seven villages from the Conservancy Dam is the charming little village of Jacoba Constantia. Almost all of its 25 five lots are occupied, and its residents have quite a love for flowers, a lot of which flowed from the yards onto the parapets.

Just how long the village has existed, no one knows for sure; probably as long as the canal has existed or before. One elderly resident did say that her parents lived in Canal Number One, just like she did, and mentioned that her father’s parents had arrived from India and later settled there.

Dhanraji Jagarnauth was resting in bed when I showed up but did not hesitate to get up and start a conversation. At 90 years old, she is the oldest resident of her village. She bore 12 children, but one of her four boys passed away. Two of her children, she proudly stated, worked at the Georgetown Hospital: Dr Rajnauth Jagarnauth and Nurse Tarmattie Barca, who have both retired. Nurse Barca retired just last June from her position as Chief Nurse. Some of her other children, she boasted, are head teachers of various schools and her son who was home with her at the time is a vet. “I tried hard with them,” she said.

Jagarnauth was born at Studley Park. Her parents were also born there and her father’s parents, who were indentured labourers from India, settled there after indentureship ended. “It had a red brick road and grass was growing in the middle. When I had to write Common Entrance, my father and me walk out to Bagotville [close to seven miles] then we ketch the bus and went Vreed-en-hoop and take the steamer from Vreed-en-hoop… He wait on me and we come back after.”

By the time she was 15, her parents had already found her a suitor and when the day came, she and her sister, who was 17 at the time, both got married. “You nah meet

yuh husband until the day you marrid,” she said. “Yuh jus a watch out to see who is the dulaha [bridegroom] that ah come. Then you nah bin know nothing. Them lil lil kindergarten baby ah ask yuh question today. Nowadays pickney can buy yuh and sell yuh.”

Her late husband, Dada Jagarnauth commonly known as Dada Persaud, worked as a printer. He was from Kitty and after they married she moved there to live with him. Eleven years later, they bought the land where her house is today. She cannot quite remember how much they paid for the property but says it could not have been more than $500. She remembers well that there were 2 coconut trees at the front of the yard and a huge star apple tree in the back which they had to cut down to facilitate the builiding of the house.

After their move to Jacoba, Dada would cycle to Vreed-en-Hoop every day and take the ferry to Georgetown to work. One day during the 1964 disturbances, while on his way home, he was pulled off his cycle and beaten at Bagotville; he played dead to avoid anything worse happening to him. He lost a few of his teeth, his widow shared, adding that people were being killed at the time.

“Yet with all of this Jacoba was peaceful. We hadn’t nothing racial here. The African people live nice with me. It was them who gave me faith that everything will be alright,” she said.

The woman added that to help her husband provide for their huge family, she reared their cows, sold the milk and also used the fat from the milk to make ghee. She recalled that her ghee was sold as far away as Trinidad. She also planted a small farm. The crops were mainly cassava and plantain, she said, laughing as she recalled that she made cassava bread and pone for her children to eat.

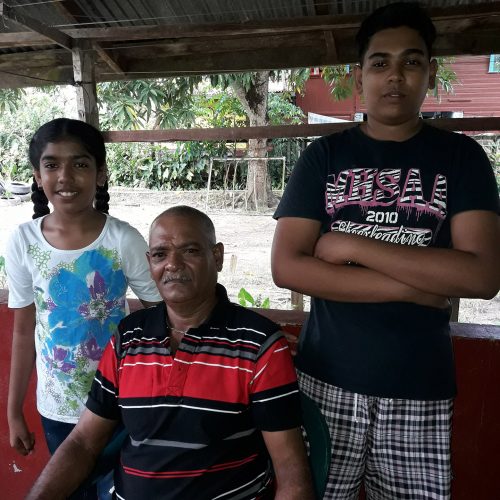

Hamed Zamal was born and raised in Jacoba Constantia. The name of the village, he said, is derived from the Dutch. Most persons refer to the village as Jacoba, he noted.

“Those days we used fireside and bug juggie [flambeau],” he recalled. “We had neighbours who were more homely, more cooperative and more loving. Long years ago, the first thing you do was look out your window and say good morning to your neighbour. I see one of my neighbours reach 106, I was 19 at the time. People used to check up on you more. If they ain’t see you couple morning, they asking for you. Now people don’t have time for you.”

His family planted ground provision: eddo, dasheen and yam. They also reared creole fowls which made a tasty meal. “In those days if you buy a white fowl, you had to have money,” he noted. “We couldn’t cook the creole fowls often. When it cook, you get couple small piece, you push it in the corner of you plate and eat you rice then you ask for more rice and surwa [gravy] and when that finish, you take you time and enjoy you meat. Meat was like ice apple at Christmas time. When you get a small piece, you suck it and put it back then eat lil lil piece till it done.”

To preserve the meat, it was salted and dried.

As a little boy, Zamal attended Mc Gillivray Primary but unfortunately, he had to leave school at the age of 12 to work on the farm. Most of the produce was taken to Stabroek Market by boat to be sold. The man recalled being paid a dollar a day to work in the farm and 50 cents when he worked half day. Recalling his primary school days, he boasted that his two cents would buy enough pholourie to feed 10 children.

Comparing life today to his boyhood days Zamal said, “Nowadays you cook ground provision, you want the children throw the provision out the house, the pot and you too. Back then if the cassava or eddo still hard, you had to soften it; you can’t waste food. Everybody living nice now. Lots of chicken to eat.”

In the years gone by, Zamal’s parents travelled to Georgetown for groceries. He recalled taking the wooden bus, which had the capacity to carry 50 passengers, to Vreed-en-hoop and then a ferry to the city. The ferries were the Makouria, the Malali and the Torani.

“Long ago was beautiful, man,” he reminisced.

What Jacoba needs, he said, is better drainage and irrigation. During the 2005 Great Flood, the farms suffered huge losses and farmers received $50,000 compensation. Zamal was one of these farmers. Flooding still occurs, but not of that magnitude; he was not affected by the recent December flood, but other farmers were.

In addition to better drainage, with school being out, he said, it would be nice if there was something constructive being offered for children to do. His daughter Alejandra said she was already bored at home with only two weeks gone and wondered how she was going to spend the remaining six; she added that school was never boring.

Harripaul Shivcharran sat in his wheelchair by the door reading a newspaper. He did not want to be photographed. Shivcharran, a former headmaster of Providence Primary, retired 17 years ago, after 37 years of unbroken service with the Ministry of Education. He began his teaching career at Kawall Primary School then later completed training at the Government Teachers’ Training College. In 1969, when he left college, he opened the Two Brothers Primary School and lived in a home given to him by the parents of pupils of the school.

In 1972 he bought his own place in Jacoba. Two years later, the main road was pitched. Before this the road was made of red brick but the mode of transportation was mainly boats. At the time Shivcharran moved to Jacoba, most of the land was owned by five families. In fact, he said, one particular man owned ten lots with each lot a mile in length. Jacoba was eventually divided into 25 lots.

Back then, Shivcharran said, the people grew mainly sugar cane, so much in fact that there was hardly anywhere to walk. Leonora Estate had taken an interest in Canal Number One Polder and so the people invested in cane. It is much different today with the sugar market fast declining.

“It’s peaceful, quiet and the people are cooperative and understanding; they are quiet and friendly. Here, you find everybody including the youths gainfully occupied,” he said.

Also a retired Regional Democratic Councillor, Shivcharran would spend his time planting and reading his newspapers; two newspapers every day and four every Sunday, and his week is complete. However, due to a recent accident he is confined for most of the day. In front of his yard there were dozens of passion fruit plants, which he plans to distribute to farmers in the Canal Polder through the Neighbourhood Democratic Council.

Speaking on development, Shivcharran mentioned that residents once had telephones operated by GTT via the dish method, but they have long since been dismantled. “I wish they could bring back telephones because cell phones are too expensive to maintain,” he said.

Drainage and irrigation, he further said, needs improvement especially for the sake of the farmers.