Dear Editor

As can be expected Dr. Henry Jeffrey in his ‘Future Notes’ of SN August 8, raised the bar in relation to recent discussion on cooperatives and their relevance as an engine of growth at this juncture of an economy virtually threatened with an overflow of oil and gas. For this reader it was a very instructive commentary.

Notwithstanding, it occurred to me that it would do no harm to repeat the anomalous experience of a private company, namely, Bookers Sugar Estates, initiating the development of cane farming cooperatives.

But it was in the late 1950s when Bookers created a cane farming community called Belle Vue on the West Bank, Demerara. Fifty-five sugar workers were selected from across the industry and allocated each 15 acre plots. Bookers accommodated them in a housing scheme built for their families, provided space for each to grow a kitchen garden, and constructed a community centre and playing field. It was a bold experiment in cooperativism which was, however, not formalised until years later, actually 1965.

The cane grown was to be supplied to the Wales Estate at a price that would cover the cost of technical assistance in growing cane provided by the estate.

The story is told that in the early 1960s when Jock Campbell was Chairman of all Bookers, he was engaged by then Premier Cheddi Jagan about restructuring the sugar industry – simply put by allocating cane lands to each employee – not coincidentally exactly 15 acre plots. It was well known that these two gentlemen enjoyed a very positive relationship, which Campbell exploited to conclude a compromise formula of small cane farming projects, to which Dr. Jagan apparently agreed.

As a result, a Cane Farming Development Corporation was established, its shareholders being Bookers Sugar Estates Ltd, Demerara Co. Ltd, Barclays Bank DCO (now GBTI) and the Royal Bank of Canada (now Republic Bank). The capital sum to be disbursed was just under G$4m, specifically to cane farming groups who were required to be registered as cooperatives, by a very active Department in those days. (Individual farmers were also considered eligible). The undersigned was at all times the appointed BSE representative, including the responsibility for organising interested village farmers into cooperative societies. This mechanism was deemed necessary so that the societies could legally qualify for loans from the Cane Farming Development Corporation (CFDC).

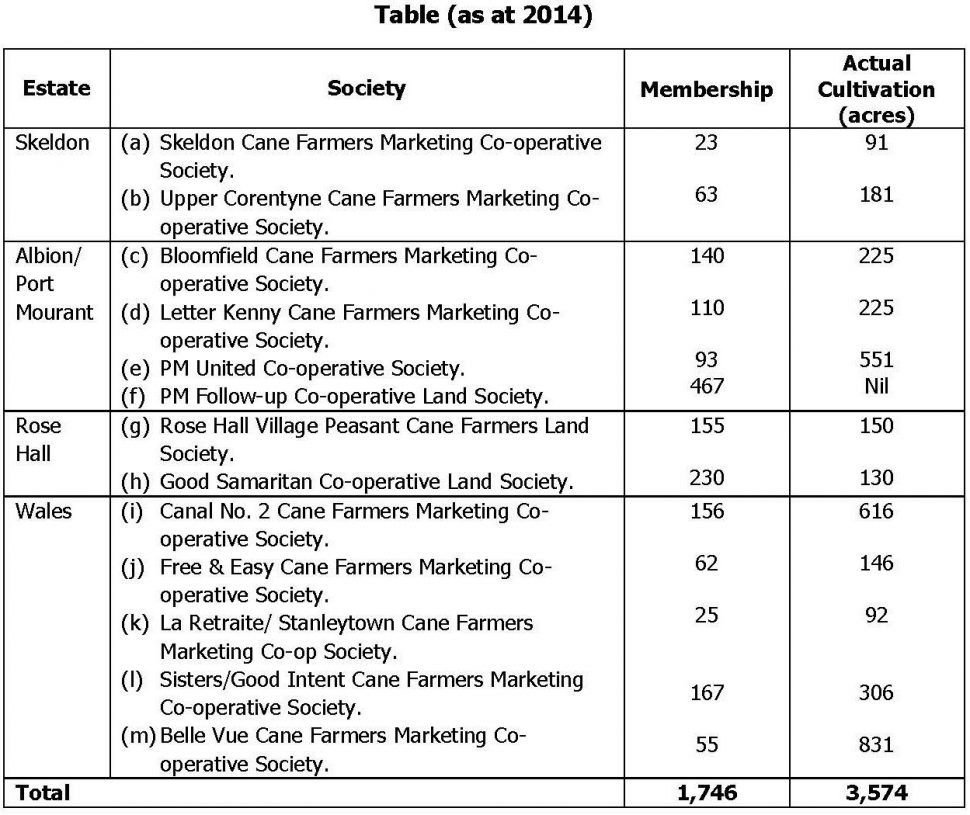

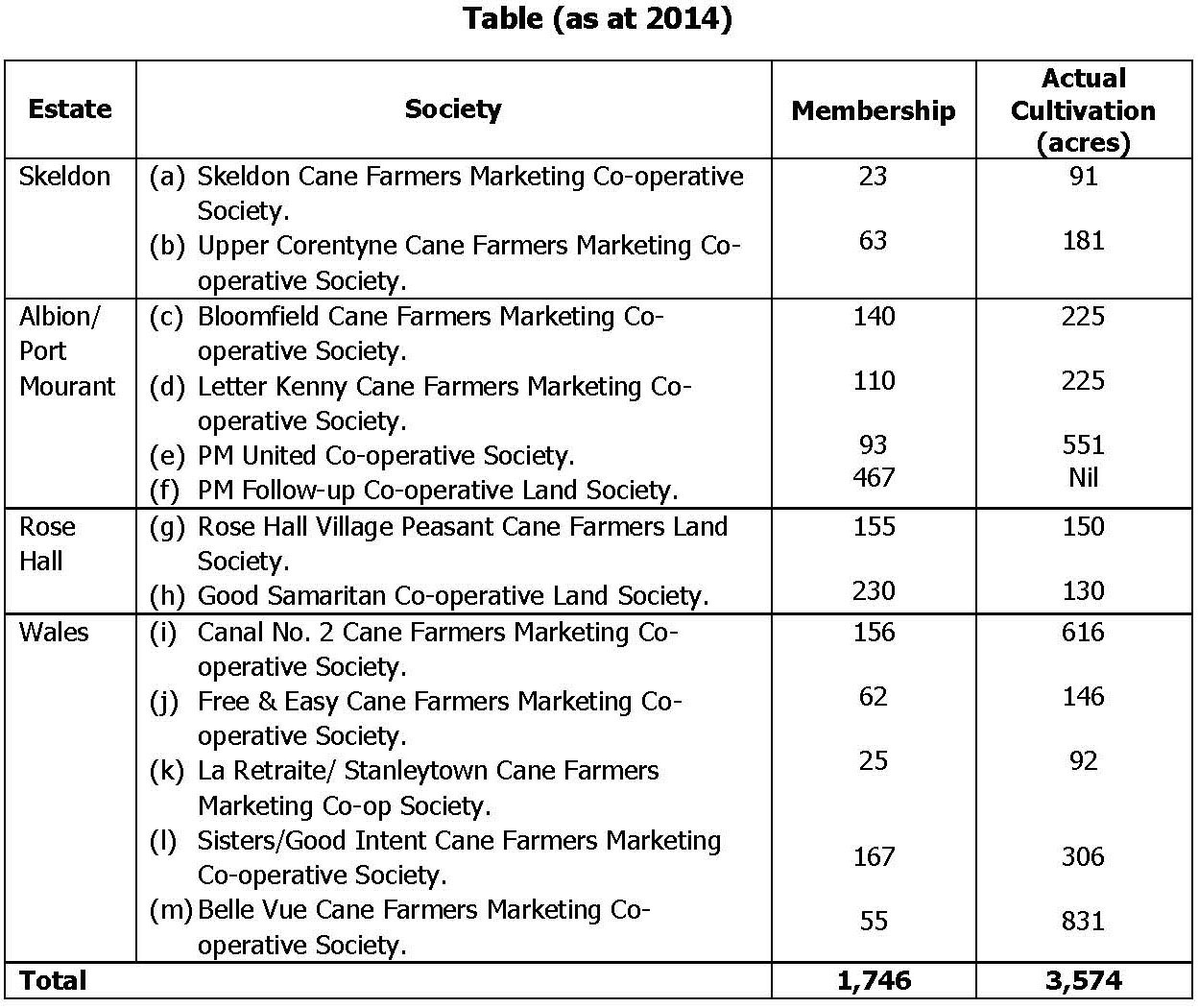

It was arduous but rewarding work, as reflected in the development shown in the table below. Note too that all transactions were conducted under the National Cane Farming Committee Act (1965), with the Regulations to the Act constituting of a Contract which established in detail the relationship between the Manufacturer (Estate) and the Cane Farmer (Cooperative and individual). The Legal Draftsman at the time was the recognisable Keith Massiah. The whole structure was overseen by a National Cane Farming Committee (NCFC), constituted largely of farmers who represented identified cane farming Districts.

Of course, included in the legal construct was the formula on which the price of cane supplied to the estates was calculated.

At the same time, in order to ensure that appropriate attention was given to the farmers’ sugar cane cultivation, each estate was required to assign a Cane Farming Liaison Officer to supervise and provide the critical technical assistance.

The following table shows the relevant data as at 2014. But those numbers have since been affected particularly by the closure of Skeldon and Rose Hall Estates. Fortunately the former Wales Estate farmers have agreed to transfer their canes to Uitvlugt Estate, to facilitate which a special roadway has been constructed.

The cooperative spirit still endures at Albion/PM and Uitvlugt Estates.

Yours faithfully,

Earl John