HERZOGENAURACH, Germany, (Reuters) – Tommie Smith, the former U.S. sprinter who won Olympic gold 50 years ago, is glad his decision to raise a black-gloved fist on the podium has inspired others even if it cost him his running career, as he sees a groundswell of support for equality.

“I knew it would have an impact but I didn’t know how far it would go,” the 74-year-old Smith told Reuters in an interview ahead of the 50th anniversary of the protest on Oct. 16, 1968.

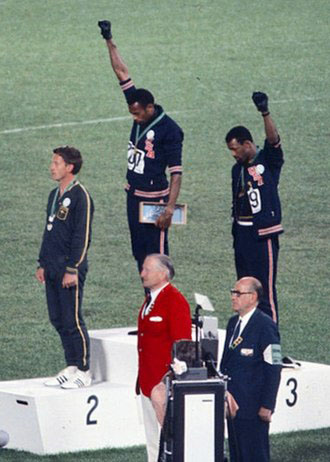

The image of Smith and fellow African-American athlete John Carlos – gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter sprint in Mexico City – bowing their heads and thrusting right and left gloved fists respectively into the air became an enduring symbol of the turbulent 1960s and the fight for racial equality.

“It was a calling for me to do it…A lot of people had died for the sake of equality. That was my chance. I had a platform.”

The protest has attracted renewed interest since quarterback Colin Kaepernick began a wave of African-American players in the National Football League refusing to stand for the national anthem to protest against racial injustice in August 2016.

Smith, who met Kaepernick last year, said he believes that there is much broader support for non-violent protest nowadays than in 1968, pointing to the success of the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements.

“Things are getting bigger and better and, if one doesn’t watch out, control (of protests) will be very, very difficult,” he said.

The fist-raising at the 200-meter victory ceremony in 1968 was widely interpreted as a black power salute, but the athletes later described it as a “human rights salute.”

HEAVY PRICE FOR PROTEST

After the protest, Smith and Carlos were suspended from the U.S. Olympic team and sent home, where they received death threats and hate mail.

Carlos’s wife committed suicide, Smith’s first marriage collapsed and both men struggled for years to make a living.

“I’ve been paying for it ever since. I have not missed a payment. I see it every day,” Smith said, adding he would have liked to try competing in hurdles if he had not been banned.

Smith spoke to Reuters at the headquarters of German sports brand Puma, which has sponsored him since 1966 and is featuring the athlete in its campaign for the 50th anniversary of its Suede shoe that Smith carried to the podium in 1968.

U.S. rival Nike has drawn massive attention this month for a new advertising campaign featuring Kaepernick, drawing criticism from U.S. President Donald Trump.

Kaepernick and other NFL players sparked national debate with their protests aimed at addressing police brutality against minorities, racial injustice, and reforming the criminal justice system. Trump has denounced players for kneeling during the anthem at games, questioning their patriotism.

“TAKE THE GOOD WITH THE BAD”

Smith, who met Barack Obama, the first black U.S. president, – in 2016, avoided commenting on current U.S. politics, beyond saying: “You have to take the good with the bad.”

Smith set 11 world records including the 200- and 400-meter marks and was just 24 when his career was cut short. He said he had the “gift of speed” just like Jamaican multi-Olympic gold sprinter Usain Bolt, who, like Smith, towers well over 6 feet.

Nevertheless, Smith says he has few regrets, adding that he was just as proud of married life and teaching track and sociology as of the rest. “Without sacrifice, there can be no forward movement. You have to give up something before you can receive something and usually that something is much better,” he said.

“I was also a school teacher who did something on the academic side. That’s pride to me.”

A towering figure who is still in good shape, Smith said he works out at the gym twice a day, but has cut back on running in the last decade.

One of a sharecropping family of 12 children who grew up in Texas, Smith said his humble upbringing taught him to appreciate life. “I learned how to work and be happy with what I was doing. I still love chicken and rice. I’m a simple person.”

Both Smith and Carlos, 73, a champion and record-setting sprinter in other major track events, are now in the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame.