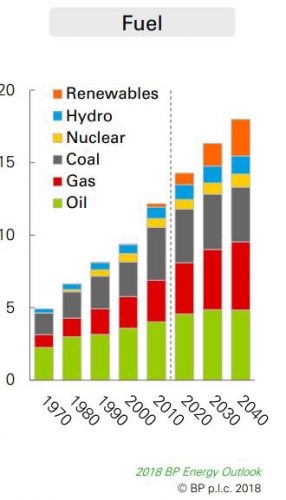

LONDON (Reuters) – Sometime in the next few weeks, global oil consumption will reach 100 million barrels per day (bpd) – more than twice what it was 50 years ago – and it shows no immediate sign of falling.

Despite overwhelming evidence of carbon-fuelled climate change and billions in subsidies for alternative technologies such as wind and solar power, oil is so entrenched in the modern world that demand is still rising by up to 1.5 percent a year.

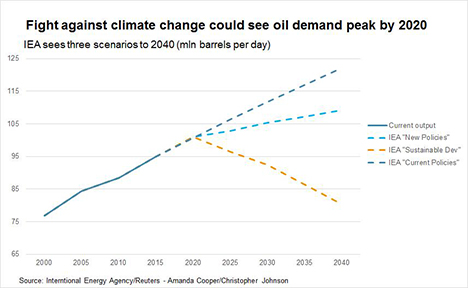

There is no consensus on when world oil demand will peak but it is clear much depends on how governments respond to global warming. That’s the view of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which advises Western economies on energy policy.

As Bassam Fattouh and Anupama Sen of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies said in a presentation last month, the debate over peak demand “signifies a shift in perception from scarcity to abundance”, which is already changing the behavior of all players in the world oil market, including exporters.

“Taking the ‘peak demand’ argument forward, it is generally thought that the world is on the brink of another energy transition, in which conventional sources such as oil will eventually be substituted away in favor of low-carbon sources.”

OPEC Secretary-General Mohammad Barkindo told a conference in South Africa on Sept. 5 that global consumption would hit 100 million bpd this year, sooner than anyone had projected.

With a sophisticated global infrastructure for extraction, refining and distribution, oil produces such a powerful burst of energy that it is invaluable for some forms of transport such as aircraft.

Of the almost 100 million barrels of oil consumed daily, more than 60 million bpd goes for transport, and alternative fuel systems such as battery-powered electric cars still have little market share.

Much of the remaining oil is used to make plastics by a petrochemicals industry that has few alternative feedstocks.

Although government pressure to limit the use of hydrocarbons such as oil, gas and coal is increasing, few analysts believe oil demand will decrease in the next decade.

If the current mix of policies continues, the IEA expects world oil demand to rise for at least the next 20 years, heading for 125 million bpd around mid-century.

Oil demand would rise less quickly if governments moved some way toward reducing the use of carbon-based fuels, putting into action already-announced plans, the IEA says.

But it warns governments that existing plans are unlikely to make a huge dent in carbon emissions, and only a thorough change in energy use will bring down oil demand.

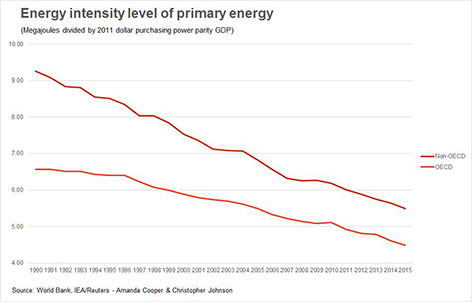

The problem for the countries the IEA advises is that they

are no longer primarily responsible for rising oil consumption.

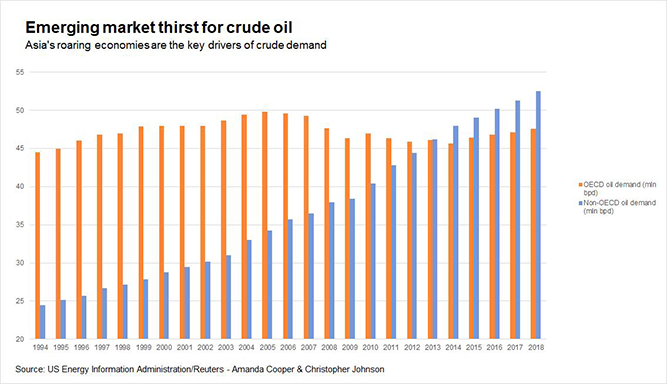

While oil demand in the big, developed economies has stalled, consumption is increasing rapidly in countries outside the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Non-OECD oil demand has almost doubled over the last two decades as new industries develop in countries across Asia, Central and South America and Africa.

The research unit of China National Petroleum Corp predicts China’s oil demand will top out at around 13.8 million bpd as early as 2030.

Some analysts argue world oil demand could come down much faster if there were more efficiency gains in vehicles, greater market penetration by electric cars combined with lower economic growth and higher fuel prices.

Investment in solar power is rising rapidly and even Saudi Arabia, the de-facto leader of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, is supporting the industry, creating the world’s biggest solar power project.

Goldman Sachs has said oil demand could peak by 2024 under some circumstances, but slow adoption of new technology in less-developed economies could delay the change.

Consultancy Wood Mackenzie is somewhere in the middle of the range, expecting demand for transport to flatline from 2030 and overall use to peak in 2036. Its chief economist, Ed Rawle, argues a fall in oil demand is coming, whatever happens:

“The signs of peak oil demand really are there into the future. It’s a question of when, not if.”