This year, the Toronto International Film Festival made a concerted effort to shine a spotlight on women both in front of, and especially behind, the camera. A number of major releases in the Gala and Special Presentations categories, even when directed by men, depended on female talent in front of the screen, such as “A Star is Born,” “Widows,” “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “The Hate U Give” and “Roma.” These were stories where women seemed to be carrying the world on their backs. Behind the camera, 34% of films at the festival were directed by women.

There was a dynamic offering of female filmmakers on show but what stood out, especially in the Discovery and World Cinema categories, was the way that key female directors from around the world turned their attention to the female experience, particularly with an eye on younger girls navigating hostile worlds.

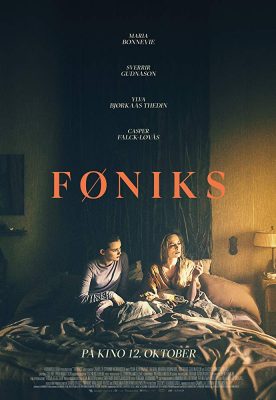

Camilla Strøm Henriksen’s “Phoenix” and Rima Das’ “Bulbul Can Sing” both explicate this point excellently. The films examine varying locales and different time periods but both of them are made vivid and affecting for the way they represent the plight of the teenage girl as a tragic figure labouring under the pressures of the world.

” her debut film, harrowingly emphasises the relentless loneliness of a young Swedish girl torn asunder. The first shot, that of a pensive face of a young girl, is the critical centre from which the remainder of the film emanates. This girl is Jill. She lives with her mother and younger brother in a modest apartment. She returns home to the remnants of a celebration and is slightly confused for her birthday, her fourteenth birthday, is days away. We realise, soon enough, that the pseudo-celebration is for her mother, and not for Jill. Astrid, her mother, is a temperamental artist and the prospect of a new job in a gallery momentarily injects enthusiasm in her erratic cadence. But this enthusiasm does not last for long as we soon realise Astrid’s mental health issues – a crippling bout of depression – threaten to disrupt any semblance of peace in the family.

” her debut film, harrowingly emphasises the relentless loneliness of a young Swedish girl torn asunder. The first shot, that of a pensive face of a young girl, is the critical centre from which the remainder of the film emanates. This girl is Jill. She lives with her mother and younger brother in a modest apartment. She returns home to the remnants of a celebration and is slightly confused for her birthday, her fourteenth birthday, is days away. We realise, soon enough, that the pseudo-celebration is for her mother, and not for Jill. Astrid, her mother, is a temperamental artist and the prospect of a new job in a gallery momentarily injects enthusiasm in her erratic cadence. But this enthusiasm does not last for long as we soon realise Astrid’s mental health issues – a crippling bout of depression – threaten to disrupt any semblance of peace in the family.

When Jill’s rock star father appears in the second half, the film seems to falter slightly. Henriksen gets more earnest mileage out of the dynamic between Jill and her mother, suggesting a world where female suffering seems unavoidable. Maria Bonnevie is temperamental and compelling as Astrid, unpredictable and blinding as the stars that the name Astrid recalls. Sverrir Gudnason is charming but oddly flat as the father we know cannot be the saviour Jill needs. In some ways, it’s difficult for the film to recover from the suffocating tragedy of its first half. As it reaches its close, it seems to be for a landing and at the very last minute, it seems to abandon any hope or desire for absolution and leaves us with uncertainty. It’s an uncertainty that pulverises the audience – a fourteen-year-old girl trying to make it through a world that is stultifying in its lack of sureness.

The first-time director imbues the film with some curious surrealistic touches. The mother’s paintings – serpentine mostly – come to life for Jill in a move that teases fantasy, and the gentlest possibility that her mother’s mental health issues might be hereditary. In a film so dependent on the literal, it seems odd to say I wish the film leaned more heavily into this surrealism. Henriksen has a knack for cultivating a foreboding, non-realistic mood, which makes these unreal variations some of the most exciting parts of the film.

Rima Das’ work in “Bulbul Can Sing” exists on the other spectrum. There is nary a trace of fantasy or surrealism in the form, instead the film is potently realistic. Das, whose previous film, “Village Rockstar,” has just been chosen as India’s representative for the 2018 Foreign Language Picture Oscar, is a one-woman film production team. She writes, directs, produces, shoots, and scouts all by herself. And her films—“Bulbul” is her third—are connected by their setting – Das’ home village, a small country locale. The girlhood loneliness that marks “Phoenix” is present in “Bulbul,” even if not at first. Our protagonist has friends: the charming Bonnie and diffident Sumu. Like Jill, she is only the cusp of becoming a woman. At fifteen-years-old, her reedy voice does not seem to impress her vocal teacher. And, in fact, all the adults at her school seem to exist on a wavelength somewhere beyond from the students. Das is as interested in the locale of Kalardiya as she is in her characters, so that this rustic village is tenderly shot with its flora and fauna and almost idealistic aestheticism. But, everything cannot be ideal, and Bulbul and her friends yearning to grow up are kept repressed by the limiting sexual mores of the village. Very soon, though, tragedy strikes and Bulbul is forced to grow up in ways that rend the heart and force her to find her voice.

“Bulbul”, like “Phoenix”, asks us what kinds of world we are creating for girls turning into women that forces them to have the grace of women but the sensibilities of children. Jill and Bulbul are both trapped in a weird purgatory between childhood and adulthood that seems doubly egregious when we consider they are only 14 and 15. The films suggest that it doesn’t matter whether in the city in Sweden or the country in India, the lives of teenage girls instead of being filled with joyous exuberance and innocence is marked by a weight of maturity, of family, of responsibility of society that only serves to rob them of their present as well as their future. It’s a sobering thesis in both films and one that feels all too relevant. Henriksen ends on a desolate note. A hardened Jill looks forward to the future that seems gloomy but one which she seems ready to steel herself to survive. Bulbul, in its closing, finds a tinge of hope that is not absolute but is encouraging. It is as if after all the hardship, Bulbul realises that she can sing. It does not make the struggles before less difficult but both films argue that perhaps the resilience these lonely girls will come to find will make the world they face better. If only.

“Bulbul”, like “Phoenix”, asks us what kinds of world we are creating for girls turning into women that forces them to have the grace of women but the sensibilities of children. Jill and Bulbul are both trapped in a weird purgatory between childhood and adulthood that seems doubly egregious when we consider they are only 14 and 15. The films suggest that it doesn’t matter whether in the city in Sweden or the country in India, the lives of teenage girls instead of being filled with joyous exuberance and innocence is marked by a weight of maturity, of family, of responsibility of society that only serves to rob them of their present as well as their future. It’s a sobering thesis in both films and one that feels all too relevant. Henriksen ends on a desolate note. A hardened Jill looks forward to the future that seems gloomy but one which she seems ready to steel herself to survive. Bulbul, in its closing, finds a tinge of hope that is not absolute but is encouraging. It is as if after all the hardship, Bulbul realises that she can sing. It does not make the struggles before less difficult but both films argue that perhaps the resilience these lonely girls will come to find will make the world they face better. If only.