this is the place

mark its name

the streets you must learn to remember

there are special songs here

they do not sing of you

in them you do not exist

but to exist you must learn to love them

you must believe them when they say

there are no sacrificial lambs here

the houses are warm

there’s bread there’s wine

bless yourself

you have arrived

listen

keys rattle

locks click

doors slam

silence

roomer

here I cower

from the day’s

drain and glare

a shadow

a wrinkled skin

cover me gently

night’s linen

prepare me

prepare me

separate ways

stranger in the sunset

I long to know you

To touch the poem of your presence

To dispel this loneliness

But the sun darkens

And we go our separate ways

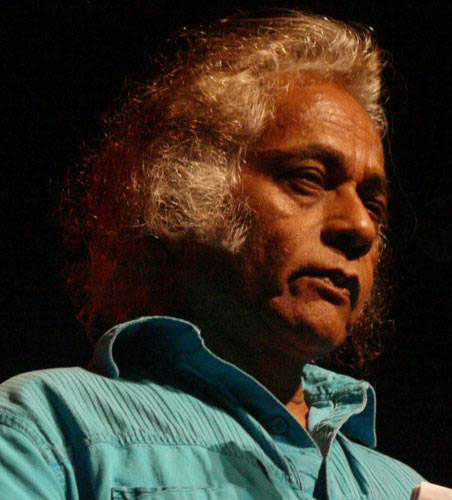

Arnold Itwaru

These selected poems by Guyanese writer and academic Arnold Itwaru make statements about contemporary Guyanese literature and about Itwaru’s contribution to it.

They appear in the anthology Concert of Voices edited by Guyanese literary critic and academic Victor Ramraj in a collection that he further subtitled “An Anthology of World Writing in English”. We have noticed this publication before, referencing the way the anthologist draws together in one volume a sample of world literature that shows something of various national literatures. The selections make statements about literatures in English, although, with no surprise, it is predominantly of the Commonwealth and North America.

In the case of Itwaru, it is Guyanese poetry. Dr Arnold Harrichand Itwaru was born in British Guiana and moved to Canada in 1969. He studied at York University and became the Programme Director for Caribbean Studies at the University of Toronto. Apart from non-fiction writing about the Canadian experience, he has published collections of poetry, which include Entombed Survivals (1987) and Body Rights: Beyond the Darkening (Tsar Press, 1991). The outlook in the poems of the latter is very much what is reflected in “arrival”, “roomer” and “separate ways” reproduced above.

But it is as a fiction writer that he is best known in Guyanese literature, as the author of his only novel, Shanti (Peepal Tree, 1988). It is of interest to the literature that it was one of the earliest publications of Peepal Tree Press, whose origins may be found in the study of Guyanese literature and East Indian culture by Jeremy Poynting. The press was founded by Poynting with its very first title – Backdam People (1986), Rooplall Monar’s first and best collection of short stories. The press took its name from the peepal tree which was imported to British Guiana from India and is very symbolic and important to Hindus.

This is all relevant to the work of Itwaru because of its contribution to at least one part of the literature. Peepal Tree has grown phenomenally since 1986 and 1988 from a one-man operation in Leeds, England, to the leading and most prolific publisher of West Indian literature today. But its origins are found in the leap forward of what may be termed Guyanese East Indian literature, and in turn, Guyanese literature as a whole.

Backdam People, which earned Monar a Judges’ Special Award in the Inaugural Guyana Prize of 1987, was the first Guyanese fiction since Sheik Sadeek in the 1960s – 1970s, to truly interrogate working class life among Indians in sugar cane and rice. That was an extremely important march forward in the national literature. Edgar Mittelholzer had done this earlier for rural Indian peasants in Corentyne Thunder (1941) in a way not achieved by Jenkins, Webber or Walrond before him.

Itwaru’s Shanti (1988) takes the literature where it had hardly gone before Sadeek or Monar, into the real experience of the plantation workers in the brand of social realism advanced by Mittel-holzer. The heroine, Shanti, grew up in the shocking reality of estate life no doubt narrated several times in the literature, but which was a new development in 1988. The novel treats her struggle with self esteem and identity, as she is scarred by the problems in a post-indentureship community. There is violence, rape, poverty, race, exploitation and other villainies involving the Indians, the whites and the blacks. The novel very much explores identity, history and vengeance in the interaction among several key characters, but leaves the lasting image of the heroine, Shanti, afflicted with the curse of the social and historical outcomes of that society.

That novel is Itwaru’s contribution to the literature where the rise of the Indian ethos as treated by the nation’s writers is concerned. But it does not sum up his total contribution or place in the literature. The poems printed above reveal more about that place. Itwaru’s poetry demonstrates the diversity present in contemporary Guyanese literature. Several different writers have moved the writing in many diverse directions, particularly in the last decade of the twentieth century.

These poems are modernist and two of them come from his first collection Entombed Survivals. They reflect the bleak outlook, the discordant discontent of modernist verse. Note the style which is undisturbed by punctuation, including the total absence of capital letters, which contribute to a sparseness, uncertainty.

In “arrival” there is a faceless namelessness. The poem’s persona draws attention to names, streets and special songs, but provide none. In spite of that everything is nameless and without identity. “You” do not even exist. The lack of place, of direction remains typical of lost modern humanity. The “arrival” is very ironic – warm house, bread and wine, the blessing, keys, doors, sounds that they make, but all consumed by an emphatic silence. “You” are thoroughly negated in the poem which keeps saying you have arrived.

The other two poems have their own share of absent optimism and accord. These poems are universal and preoccupied with humanity and the human condition, which are still features of Guyanese poetry. Itwaru, therefore, who has been very much concerned with exile, has brought those qualities to Guyanese literature – a strengthening of the rise of the Indian presence and a contribution to the universal concerns that are substantial in contemporary Guyanese literature.