![]() Amandla Stenberg was one of a handful of actors who attended the Toronto International Film Festival this year as the star of two films. She was the top billed star of Amma Asante’s World War II drama “Where Hands Touch” and George Tillman Jr.’s contemporary drama “The Hate U Give.” Decades and miles apart, the films are connected by a sobering awareness that whether Germany in the 1940s or Garden Heights in 2019, it’s not easy being a black girl.

Amandla Stenberg was one of a handful of actors who attended the Toronto International Film Festival this year as the star of two films. She was the top billed star of Amma Asante’s World War II drama “Where Hands Touch” and George Tillman Jr.’s contemporary drama “The Hate U Give.” Decades and miles apart, the films are connected by a sobering awareness that whether Germany in the 1940s or Garden Heights in 2019, it’s not easy being a black girl.

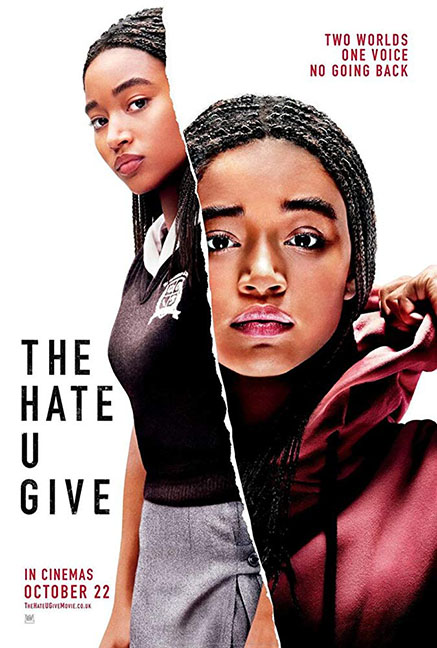

Based on a critically acclaimed young-adult novel, “The Hate U Give” opened this week in Guyana, and is the latest in a consistent trend of young-adult texts giving way to star-studded film adaptations, but it takes on a propulsive energy that gives way to a lacerating anger that feels necessary and welcome in 2018. Stenberg’s Starr Carter is a 16-year old girl who must navigate between the mostly black (poor) neighbourhood where she lives and the mostly white prep school society. This fragile world of constant code-switching is broken when her childhood friend is murdered by police—a travesty which Starr is witness to. From there what artificial peace has kept Starr and her family afloat is broken to give way to the chaos and uncertainty that comes with being a black person in America.

It’s important that “The Hate U Give” is a young-adult film, and it’s important that Stenberg, who has industriously earned her place among the young Hollywood elite since her breakout role in “The Hunger Games,” is the centre of it. It’s been alarming, if unsurprising, the way the film—an outside contender for end-of-year-awards—has been indicted for the way it leans into its young-adult tropes. “The Hate U Give” presents the necessity of a world where racial injustice, police brutality and racial strife are topics that are important enough for a teenager. Starr and one of her white school friends have an argument about racial allegiances that hinges on one of them unfollowing the other on Tumblr. It’s such a searing and true teenage incident and Audrey Wells’ screenplay chooses not to undermine that youthful verve but instead leans into it. It’s this deft awareness of teenagers as ungainly children with their own way of interactions that makes “The Hate U Give” so valuable. Even though the film begins with Starr’s father (a very dependable Russell Hornsby) teaching his children about blackness in America, everything about Starr in that first act, from her deliberately awkward narration to her school life, feels painfully youthful. From her rapport with her brothers to the introduction of her maybe-boyfriend with a beautifully cheesy dance sequence, it feels unformed. The film gets teenagers in a way that’s thoughtful; it does not force them into adult behaviour but keeps them grounded in childlike naivety. And it’s grounded by Stenberg layering Starr with a depth and nuance that you cannot look away from. Tillman Jr has a history of providing context and complexity to black lives on screen. His 1997 film “Soul Food” still feels revolutionary two decades later, which is tellingly unfortunate.

His direction here presents family and community as a focal point of the narrative, with Regina Hall turning in a performance of restless motherhood in the edges of the picture that affects as a key secret-weapon. The presentation of a black family focused on togetherness in moments of minutiae as well as bigger ones feels profound and essential in a studio system that still, too rarely, affords black casts that opportunity. This idea of community is what defines the film. The film’s casting wields that idea of community with new black stars (Stenberg is joined by Issa Rae, another new member of the young Hollywood elite) and more familiar faces like Hornsby, Hall and Common (as a well-meaning uncle). Community is the only way for black people, the film argues.

When Starr’s well-meaning white boyfriend says “I don’t see colour. I see you,” we groan at his faux pas, aware of the way erasure of racial context does not privilege persons of colour. The film is deft and warm enough to meet his teenaged ignorance with a necessary comeback that is assertive but not despotic: “If you don’t see my blackness, then you don’t see me.” What is it like to be a black girl in a sea of white? How does it feel? “The Hate U Give” joins “Where Hands Touch” with asking these potent questions. Asante’s film, inspired by true events, tells the tale of a mixed-race girl. Born to an Aryan mother, and a black father, her mother’s whiteness cannot shield her from the horrors of Nazi Germany. Stenberg’s work on “Where Hands Touch” feels like an essential rejoinder to her work in “The Hate U Give,” announcing her as a young actor with a wealth of talent. “Where Hands Touch” has come under fire for its plot. In it, Stenberg’s Leyna falls in love with a white teen, the son of a Nazi soldier and a budding Nazi himself. But the romantic arc of that film has more depth than humanising a Nazi. Asante’s film seems to meet “The Hate U Give” by pointing out the way that children’s fate are inextricably bound by the lives of their parents. The latter film earns its title from a Tupac lyric – THUG LIFE: The Hate U Give Little Infants F***s Everyone.

Stenberg, a biracial woman born to American and Danish parents, has been outspoken about the effects of biracial heritage on her place in Hollywood. That she has used what she calls her “light-skinned privilege” to announce herself as an important part of young Hollywood by starring in two films asking the world, “Can a black girl just exist in the world without being forced to defend her colour?” feels important. “The Hate U Give,” in particular, seems to solidify her place as a young Hollywood star, and it’s to her credit that her star power is being used in such compelling ways.

Email your responses to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com or follow him on twitter at DepartedAviator.

“The Hate U Give” is now playing at Princess Movie Theaters and Caribbean Cinemas