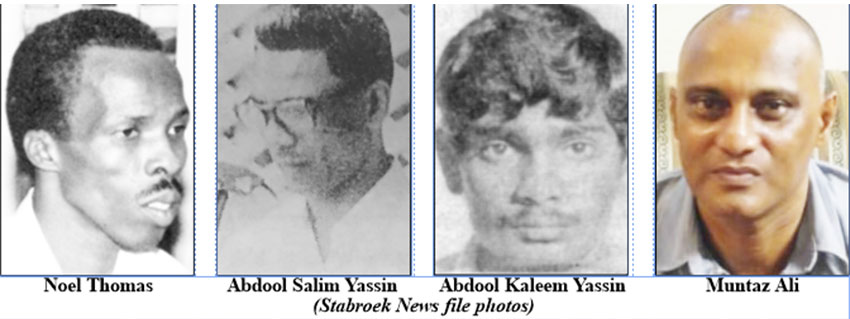

After spending a combined 64 years on death row for two separate murders, Noel Thomas and Muntaz Ali yesterday walked out the Lusignan Prison freed men after being granted parole.

Their petitions had been before the Parole Board for some six years during which numerous hearings were facilitated and submissions made on Ali’s behalf by his attorney Ronald Burch-Smith.

Thomas had presented his own petition.

The lengthy process finally came to a conclusion late last week, culminating in Minister of Public Security Khemraj Ramjattan signing the licences which effectively caters for the release of the new parolees.

Thomas who will be celebrating his 60th birthday in December now gets a taste of freedom after spending 31 years behind bars, while it has been 33 years for 52-year-old Ali.

Thomas had been convicted and sentenced to death along with Abdool Salim Yassin for the 1987 murder of the latter’s brother—Abdool Kaleem Yassin who was shot dead in his bed at his Riverstown, Essequibo Coast home on the night of March 18, 1987.

On October 12, 2002 Thomas’ co-convict died at the Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation after a prolonged illness.

Ali, meanwhile, had been convicted and sentenced to death along with Terrence Sahadeo and Shireen Khan for the 1985 murder of 18-year-old Roshani Kassim whom they also brutally raped and at her Sheet Anchor home, East Canjie Berbice.

The case of convicted duo Thomas and Yassin would, however, over the years go on to be a popular one—holding academic significance and setting judicial precedent by which courts would later become bound to follow.

Noose

“Thomas and Yassin,” as the case is popularly called and commonly referred to by many, especially members of the legal fraternity and law students alike, is historically known for the many constitutional challenges mounted by the two in a bid to escape the hangman’s noose.

The two made a series of petitions both before the local courts and even all the way to the United Nations Human Rights Committee of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

“Thomas and Yassin,” is the (locus classicus)—the local deciding authority to challenges of “cruel and inhumane punishment” often raised by death row inmates as reasons they should not be sent to the gallows.

This case sits on the same precedent wavelength with that of its Jamaican equal, commonly referred to as “Pratt and Morgan” case in which Earl Pratt and Ivan Morgan who had also mounted a series of challenges to the death sentences imposed against them after their convictions for murder also.

The cases of Thomas and Yassin and Pratt and Morgan established the judicial precedent which argues that all sentences where persons have been condemned to death and have been on death row for more than five years without being hanged, amounts to cruel and inhumane punishment.

Once such a state of affairs exists, the cases argue further that such sentences would warrant a commutation of to life imprisonment.

In the case of Guyana, however, as is evident, it does not bar a lifer from applying for parole which may be granted after considering such factors as the applicant’s eligibility and suitability.

The Parole Act of the Laws of Guyana Cap 11:08 stipulates the criteria to be satisfied for a convict applying to be paroled. Eligibility does not by itself, however, guarantee parole, as a number of variables will have to be assessed on a case by case basis to determine the applicant’s suitability for release into society.

To bolster their case against being hanged, death row prisoners in Guyana also rely primarily on Article 141 (1) of the constitution which states, “No person shall be subjected to torture or to inhumane or degrading punishment or other treatment.”

Subsection (2) of the Article meanwhile provides, “Nothing contained in or done under the authority of any law shall be held to be inconsistent with or in contravention of this article to the extent that the law in question authorizes the infliction of any punishment or the administration of any treatment that was lawful in Guyana immediately before the commencement of this constitution.”

Cruel and inhumane

Both Thomas and Yassin and Pratt and Morgan had sought to argue that being on death row for more than five years amounted to cruel and inhumane and degrading punishment or treatment.

The argument often proffered to counter this contention by those in favour of the death penalty have, however, been that the delay in executions exceeding beyond five years is usually caused by the convicts themselves who mount lengthy challenges and repeatedly seek stays of executions to facilitate those legal challenges.

A year after the murder, Thomas and Yassin were convicted by a jury at the High Court in Essequibo and sentenced to death on June 5, 1988. They appealed their case two weeks later and were subsequently granted retrials.

At the conclusion of a second trial, however, which ended on December 4, 1992, they were again convicted by a jury and sentenced to hang by Justice Claudette Singh who read the death sentences to them.

Four days later, they yet again filed appeals to the Guyana Court of Appeal which this time affirmed the capital punishment imposed by the High Court. This was done in June of 1994.

Twenty years later, however, after applying, their death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment on June 11, 2012 by former acting Chief Justice Ian Chang.

In March of 1998 the United Nations Human Rights Committee recommended the release of the appellants but this recommendation was not put into effect. In fact, on September 9, 1999 warrants were read for their executions which was scheduled to take place four days later—September 13th.

Just the day before, however, the appellants filed a writ of summons and an ex parte application by way of affidavit against the respondent/state and were able to obtain from Justice Winston Moore, a conservatory order staying their executions until the hearing and determination of the summons.

Following the hearing of arguments over an ensuing 11-day period, a judge on October 18, 1999 refused the stay until the hearing and determination of the action, thereby disallowing the filing of any pleadings followed by a trial.

They would, however, later succeed in their death sentences being commuted to life imprisonment owing to the numerous legal challenges they mounted through their attorneys.

The two were to be hanged on February 5, 1996 but were successful in securing a stay of execution after lawyers filed constitutional motions to stop the executions.

Following this, the UN Human Rights Centre had made pleas for clemency on behalf of the convicted killers as did a number of other international organisations and individuals alike.

Over the years Thomas and Yassin had been represented by a battery of high-powered lawyers which included the late Doodnauth Singh, Jainarayan Singh Jr, now-deceased Vic Puran and Nigel Hughes.

According to evidence presented by the prosecution at the trial, Yassin had hired Thomas to carry out the hit on his younger 27-year-old brother towards whom he had resentment after their father had bequeathed the bulk of his assets to Kaleem.

Yassin had reportedly retained Thomas as the ‘hit man,’ paying him a sum of $700 as a down payment on a total fee of $20,000.

On November 8, 1989 Ali, Khan and Sahadeo were all sentenced to death. They were granted a subsequent appeal and retrial but were again convicted and sentenced to death on May 26, 1994. Khan died in prison, while Sahadeo remains incarcerated.

Their death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment by the High Court on June 11, 2012.

On September 18, 1985 the three entered the teen’s home where they robbed and brutally murdered her after Ali and Sahadeo had raped her.

A knife was found embedded to the hilt in her throat and there was evidence that she was also physically abused.

In a brief comment to this newspaper on June 4, 2012 Hughes had said that Justice Chang’s ruling commuting the death sentences to life imprisonment was in line with existing Privy Council and Caribbean Court of Justice rulings to the effect that the sentences should be commuted to life imprisonment in light of the amount of time the convicts were on death row.

Hughes had further contended that because of the years spent on death row, convicts should have been released and at that time he planned on taking steps to secure his Thomas’ freedom.

The lawyer had pointed out that he was being guided by the ruling in Pratt and Morgan which was handed down by the Privy Council.

The last executions at the Georgetown Prisons were on August 25, 1997.