“Bohemian Rhapsody,” more than most 2018 films, has had to justify its existence. What does this film have to say about Freddie Mercury and Queen that demands a feature-length studio release? The film has spent almost a decade making its way to the screen, stuck in development hell, plagued by casting and creative controversies and it seems immediately significant to note that it is produced by Jim Beach, the band’s long-time manager and features surviving members Brian May and Roger Taylor as creative consultants. The subtext, or even the text, of their roles in the film immediately suggest the film as a text that is Queen as filtered through the eyes of Queen, which rather than ostensibly providing comfort suggests some amount of gatekeeping, especially in relation to its famed frontman, Freddie.

“Bohemian Rhapsody,” more than most 2018 films, has had to justify its existence. What does this film have to say about Freddie Mercury and Queen that demands a feature-length studio release? The film has spent almost a decade making its way to the screen, stuck in development hell, plagued by casting and creative controversies and it seems immediately significant to note that it is produced by Jim Beach, the band’s long-time manager and features surviving members Brian May and Roger Taylor as creative consultants. The subtext, or even the text, of their roles in the film immediately suggest the film as a text that is Queen as filtered through the eyes of Queen, which rather than ostensibly providing comfort suggests some amount of gatekeeping, especially in relation to its famed frontman, Freddie.

Mercury’s place in pop-culture is, perhaps, bigger than Queen. This is both because of his inimitable flamboyance as well as because of his queerness in a profession that often manifests itself in hyper-masculinity and at a time that was less than friendly to the LGBT community. Mercury died in 1991 due to AIDS complications; it is one of the high-profile deaths from HIV/AIDS. Mercury’s life is a big one, and one that feels so larger than life that no one text (filmic or literary) seems capable of harnessing it. Mercury’s legacy is inextricably bound to Queen, but a tale of Freddie seems separate from Queen in cultural ways that, even before the film’s release, the question of its approach to the personal life of Freddie became an issue of controversy. If “Bohemian Rhapsody” seeks to use Mercury as a figure in its text, it owes it to Freddie to present the truth of him. But what is truth?

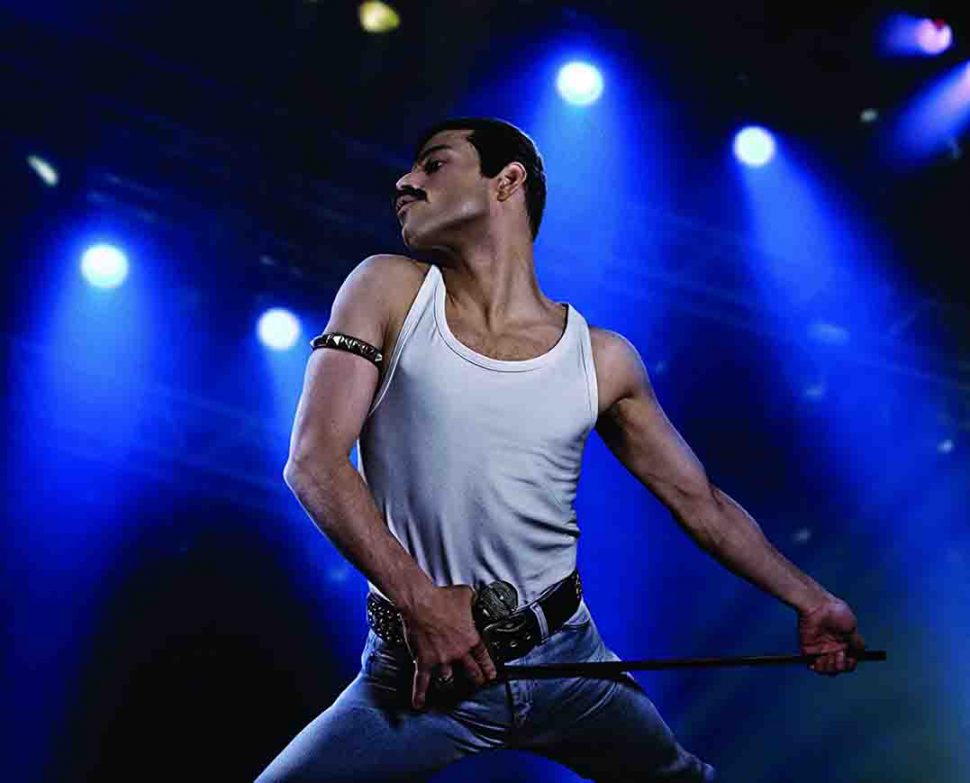

“Bohemian Rhapsody” opens with a tight close-up on the face of Rami Malek as Freddie Mercury. Except it’s not his face, really, that’s the focus. It’s his eyes. The shot is so tight, the rest of his features are obscured. We cut to a shot of his feet and other parts of his body as he gets dressed, his face consistently obscured throughout. Interspersed audio throughout informs us that we are in 1985 and brief cutaways to the Wembley Stadium indicate that we are heading to Queen’s Live Aid performance. As Mercury leaves his house, arrives at the stadium, dresses and then strips as we continue to watch him from the side or the back as the strains of the band’s “Somebody to Love” plays over the scene. Decked out in his trademark tight jeans, the white vest and jewellery, we see him saunter on stage and we cut – fifteen years back – t0 1970.

This brief opening is one of the moments in “Bohemian Rhapsody” that works well. Beyond the initial shot of his eyes, it imitates the introduction to another larger-than-life musical figure – the fictional Dolly Levi in Gene Kelly’s 1969 “Hello, Dolly!”. The film opens with shots of Dolly’s shoes, her dress, her hands, keeping us in suspense until with a turn of the head Barbra Streisand gazes out beatifically as us as she introduces herself to us – the inimitable Dolly Levi, the great fixer. Freddie Mercury is not Dolly Levi, and “Bohemian Rhapsody” is not “Hello, Dolly!” but the idea of mythmaking and fantasy seem integral to the musical biopics in ways that are fascinating even as it attempts to harness the history and the legend of the larger-than-life Freddie Mercury into a 134-minute film.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is a PG-13 film about a man who exists in history as a sexually expressive figure. That this man is queer (whether homosexual or bisexual remains the subject of debate) presents a bigger issue when Hollywood studios are often ambivalent, at best, about representing queerness on screen in explicit or sincere ways. A story about the life of Mercury, a man notably private about his life all the way his death, would almost certainly be forced to wrestle with the ideas of sexual politics and sexual identity of the seventies and eighties, except “Bohemian Rhapsody” isn’t really a film about Mercury’s life. Or even a film about Mercury the man. It’s a film about Mercury the myth.

Rami Malek, as Mercury, understands this better than any other aspect of the film in a performance that does not imitate the real Freddie Mercury (he doesn’t quite look like him for example, and he lip-syncs over the tracks) but instead suggests and embodies him in a way that’s constantly winking but never interested mimicry. Mercury, like many larger than life figures (and like the fictional Dolly Levi) must be all things to all people both within the film’s timeline and in the contemporary response to the film. His performance is slippery but not illusory. Malek nails both the tenderness of the film’s idea of Mercury as well as the arrogant bravura. It’s a performance of paradox that works better than anything in the film, and is best distilled in the film’s recreation of Queen’s set at Live Aid, where the entire sequence is recreated on screen and married with the audio from the real event.

It’s the best thing, then, that the film ends on that Live Aid sequence, which emphasises the ideological suggestion of Freddie. It’s about Freddie as a concept. The film is very much about a silhouette of a man. Freddie seems consistently unknowable until the end. What comes across is not a heretic disavowal of Freddie’s gayness, but a melancholic tone of regretful nostalgia. The film never engages with what his queerness means to him, and by ending at Live Aid we never watch Mercury wrestling with the last years of his life as a queer man with AIDS in the homophobic eighties.

If anything, “Bohemian Rhapsody” is shackled by its PG-13 rating. The film is not coy about Mercury’s queerness but is coy about sexuality in the way of many studio films. It cannot help but be so when it is tale about a libidinous man whose story is being filtered through a major studio. The level of verisimilitude we look for in films based on real events is always intriguing. “Bohemian Rhapsody” is not a political film, but it’s clear how Mercury’s queerness and death by HIV presents a cultural marker of the place of sexuality outside of heterosexual norms in American pop culture. Political histories are more fraught when it comes to bending because of the weight they have, and more recent political history is particularly at the mercy because of the temporal closeness. American society has still not reckoned with the role its government and anti-queerness played in the demise of a generation of men in the eighties. The topic is a sensitive one, and yet “Bohemian Rhapsody” is so emphatically rooted in Freddie as myth rather than Freddie as man.

But, whatever your allegiances, “Bohemian Rhapsody” isn’t interested in watching Freddie Mercury suffer. The film is about the myth of a man—a man whose mythology is ever-present and ever existing. That “Bohemian Rhapsody” chooses to end with the triumphant Live Aid performance rather than Freddie grappling with his HIV diagnosis, I suppose in the most superficial of ways might read as its lack of interest in his homosexuality but it seems like a bad faith argument and rather indicative of the film’s own interest in emphasising the myth and the man. As a live performance of Queen’s ‘Don’t Stop Me Now’ (live footage of the real band) plays over the credits, the film seems to emphasise Freddie’s place as a celestial being. Freddie lives on, the film seems to argue, and for all its imperfections that thesis seems satisfactory.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas Guyana.

Email your responses to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com or send him a Tweet at DepartedAviator.