![]()

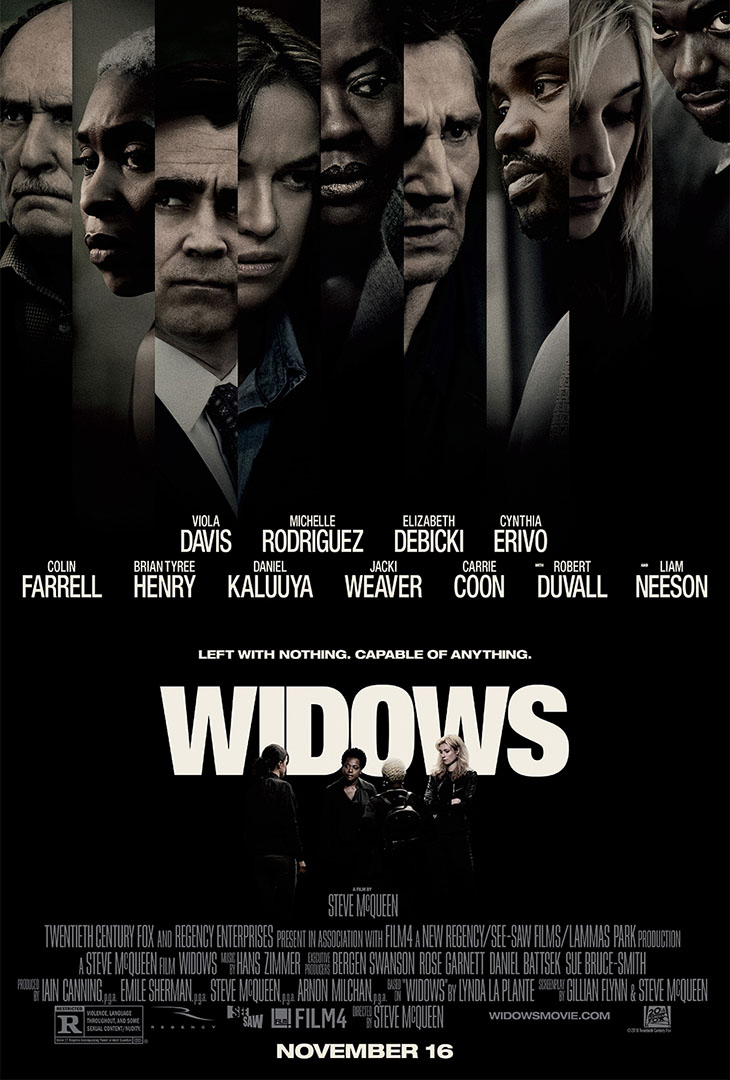

![]() Steve McQueen’s “Widows” premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in September as the much-hyped and much-anticipated follow-up to his Oscar winning “12 Years A Slave”, from 2013. The pedigree of the film runs deep, with award-winning talent in front of, and behind the camera. But the straight-forward nature of this heist film seemed slightly out-of-place amidst the more cerebral or abstruse films many mistakenly identify with film festivals. Even as “Widows” emerged as a well-made and stylish foray into the world of criminals, its festival premiere seemed to be summed up by a critic I overheard mulishly complain after the premiere, “I expected something more complex from McQueen.” His words emphasised the way expectations play into our reaction to content. For, “Widows” is certainly not immediately cerebral as “Hunger” or “Shame” but the film even as it boasts blockbuster thrills, is constantly complex.

Steve McQueen’s “Widows” premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in September as the much-hyped and much-anticipated follow-up to his Oscar winning “12 Years A Slave”, from 2013. The pedigree of the film runs deep, with award-winning talent in front of, and behind the camera. But the straight-forward nature of this heist film seemed slightly out-of-place amidst the more cerebral or abstruse films many mistakenly identify with film festivals. Even as “Widows” emerged as a well-made and stylish foray into the world of criminals, its festival premiere seemed to be summed up by a critic I overheard mulishly complain after the premiere, “I expected something more complex from McQueen.” His words emphasised the way expectations play into our reaction to content. For, “Widows” is certainly not immediately cerebral as “Hunger” or “Shame” but the film even as it boasts blockbuster thrills, is constantly complex.

“Widows” is a departure for McQueen – a would-be action blockbuster rather than a meditative study, and a female-focussed drama rather than the very masculine focus of his previous works. “Widows” is an adaptation of a 1983 British miniseries which, like this new version, centres on a trio of wives who turn to crime after their criminal husbands are killed in a botched job. But, that’s only a sliver of what “Widows” is about. As straight forward as the story is this is a film that overflows with diverging, converging and competing storylines. This penchant towards excess defines the film.

The opening scene is punctuated by carnage as a group of thieves make a chaotic escape after a job gone wrong only to perish in flames. Their wives are left to grieve them, but the grief soon turns to fear when ghosts from the past appear to haunt Veronica Rawlings – the wife of the criminal mastermind Harry Rawlings. Viola Davis, as Veronica, is the de facto lead. She harnesses two other widows (Elizabeth Debicki as Alice and Michelle Rodriguez as Linda) together to fend off the fast-approaching danger. But, this main plot takes some time to get underway and “Widows” instead turns into a tale about shifting allegiances, deep-rooted corruption and ambivalent lives in contemporary Chicago.

That ambivalence becomes a critical ingredient – structurally and thematically – in the film. McQueen makes use of an ambling visual aesthetic, with the help of cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, and it recalls Robert Altman in the way the film never seems to settle as one thing, or settle on one character. McQueen’s script, which he co-writes with Gillian Flynn, seems compelled by even the most incidental character. What’s interesting is that the care McQueen’s camera has for everyone is not necessarily working towards a cohesive focus but becomes part of the film’s almost chaotic ambivalence, where each character is working at odds against the other.

That ambivalence becomes a critical ingredient – structurally and thematically – in the film. McQueen makes use of an ambling visual aesthetic, with the help of cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, and it recalls Robert Altman in the way the film never seems to settle as one thing, or settle on one character. McQueen’s script, which he co-writes with Gillian Flynn, seems compelled by even the most incidental character. What’s interesting is that the care McQueen’s camera has for everyone is not necessarily working towards a cohesive focus but becomes part of the film’s almost chaotic ambivalence, where each character is working at odds against the other.

When the title for the film first appears, the single world “Widows” appears deep to the bottom right of the screen in surprisingly fine print. It’s as if we have to seek it out, which is McQueen’s intention. This aesthetic, built on misdirection, means we find ourselves being introduced to more and more characters, finding out information at times that seem especially inconvenient. A recurring visual motif is Bobbitt’s ever moving camera where the first thing the camera focuses on always needs to be contextualised before we get the full value of it. Conversations begin, and sometimes continue throughout, with the faces of the speakers obscured. A car journey is punctuated by shots of the city outside, and the chauffeur listening in, rather than the speakers. It’s a motif that works to augment and cut against the main plot, but one which ends up inadvertently highlighting the heavy lifting the film’s sharp direction is doing in moments when its script becomes too literal, occasionally buckling under the weight of too many plots and too many characters.

At its best, though, “Widows” eschews any busy-ness that would problematise a film like this. McQueen and writer Gillian Flynn are cognisant of the value of every main character, which gives the film a potent weight, what happens, though, is we’re left to our own devices to pick our favourite turns. The main trio. and the fourth adjunct who joins them, are all excellent. Oddly, though, the ambivalence the film fosters sometimes has us going off on our own tangents, pondering on moments that are the edges of the narrative. Like, why does Veronica Rawlings seem to have no friends or family? What will become of Breechelle, a salon owner who appears briefly but is expertly fleshed out by Adepero Oduye? What will become of the fourth widow who declines the invitation to join the heist? It makes sense in the ambivalent world view we are given that these threads are left hanging, and yet the film sometimes seems less kinetic when it focuses on the the heist, which seems atypical for a heist film. This is an action film that is more engaged with psychological uncertainty than physical carnage. And so, the moments of characters abrasively brushing against each other – a slap happy moment, a glowering stare seem more exciting than the actual job to be done.

As the film hurtles to its climax, though, the value of the digressions become key. A brief scene of rapping with ancillary characters is propulsive and affecting. A conversation between Alice and her hectoring mother is brief yet taut and effective. Linda’s brief commiseration of grief with a widow she’s trying to grift adds a sharp dose of reality to the affairs as she blurts out, as if startled, “I lost my husband two weeks ago!” The digressions become key markers of character, giving the film a depth and complexity that the main plot does not always carry.

And still, “Widows” is a satisfying watch. It’s very much about those sharp edges and the pointed ellipsis. The film’s big twist when it comes feels slightly too fanciful for us to be fully invested, but it manages to emphasise the vulnerability of women in a patriarchal world that make its inelegance almost irrelevant. This is a high-octane adrenaline ride and if the comedown is a bit too sharp to be wholly comforting, watching it again to feel the thrills of its highest moment feels like the best remedy. It’s that kind of thriller. “More! More! More!”, it calls out. And, it’s so stylish in all its movement, who are we to resist something so thrilling that goes down so easy?

Widows was first screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and is now playing at Caribbean Cinemas and Princess Movie Theaters.