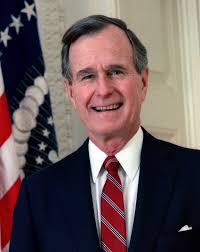

(Washington Post) George H.W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States and the father of the 43rd, was a steadfast force on the international stage for decades, from his stint as an envoy to Beijing to his eight years as vice president and his one term as commander in chief from 1989 to 1993.

The last veteran of World War II to serve as president, he was a consummate public servant and a statesman who helped guide the nation and the world out of a four-decade Cold War that had carried the threat of nuclear annihilation.

His death, at 94 on Nov. 30 also marked the passing of an era.

Although Mr. Bush served as president three decades ago, his values and ethic seem centuries removed from today’s acrid political culture. His currency of personal connection was the handwritten letter — not the social media blast.

He had a competitive nature and considerable ambition that were not easy to discern under the sheen of his New England politesse and his earnest generosity. He was capable of running hard-edge political campaigns, and took the nation to war. But his principal achievements were produced at negotiating tables.

“When the word moderation becomes a dirty word, we have some soul searching to do,” he wrote a friend in 1964, after losing his first bid for elective office.

Despite his grace, Mr. Bush was an easy subject for caricature. He was an honors graduate of Yale University who was often at a loss for words in public, especially when it came to talking about himself. Though he was tested in combat when he was barely out of adolescence, he was branded “a wimp” by those who doubted whether he had essential convictions.

This paradox in the public image of Mr. Bush dogged him, as did domestic events. His lack of sure-footedness in the face of a faltering economy produced a nosedive in the soaring popularity he enjoyed after the triumph of the Persian Gulf War. In 1992, he lost his bid for a second term as president.

“It’s a mixed achievement,” said presidential historian Robert Dallek. “Circumstances and his ability to manage them did not stand up to what the electorate wanted.”

His death was announced in a tweet by Jim McGrath, his spokesman. The cause of his death was not immediately available. In 2012, he announced that he had vascular Parkinsonism, a condition that limited his mobility. His wife of 73 years, Barbara Bush, died on April 17.

The afternoon before his wife’s service, the frail, wheelchair-bound former president summoned the strength to sit for 20 minutes before her flower-laden coffin and accept condolences from some of the 6,000 people who lined up to pay their respects at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston.

Mr. Bush came to the Oval Office under the towering, sharply defined shadow of Ronald Reagan, a onetime rival for whom he had served as vice president.

No president before had arrived with his breadth of experience: decorated Navy pilot, successful oil executive, congressman, United Nations delegate, Republican Party chairman, envoy to Beijing, director of Central Intelligence.

Over the course of a single term that began on Jan. 20, 1989, Mr. Bush found himself at the helm of the world’s only remaining superpower. The Berlin Wall fell; the Soviet Union ceased to exist; the communist bloc in Eastern Europe broke up; the Cold War ended.

His firm, restrained diplomatic sense helped assure the harmony and peace with which these world-shaking events played out, one after the other.

In 1990, Mr. Bush went so far as to proclaim a “new world order” that would be “free from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice and more secure in the quest for peace — a world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak.”

Mr. Bush’s presidency was not all plowshares. He ordered an attack on Panama in 1989 to overthrow strongman Manuel Antonio Noriega. After Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990, Mr. Bush put together a 30-nation coalition — backed by a U.N. mandate and including the Soviet Union and several Arab countries — that routed the Iraqi forces with unexpected ease in a ground war that lasted only 100 hours.

However, Mr. Bush decided to leave Hussein in power, setting up the worst and most fateful decision of his son’s presidency a dozen years later.

In the wake of that 1991 victory, Mr. Bush’s approval at home approached 90 percent. It seemed the country had finally achieved the catharsis it needed after Vietnam. A year-and-a-half later, only 29 percent of those polled gave Mr. Bush a favorable rating, and just 16 percent thought the country was headed in the right direction.

The conservative wing of his party would not forgive him for breaking an ill-advised and cocky pledge: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” What cost him among voters at large, however, was his inability to express a connection to and engagement with the struggles of ordinary Americans or a strategy for turning the economy around.

That he was perceived as lacking in grit was another irony in the life of Mr. Bush. His was a character that had been forged by trial. He was an exemplary story of a generation whose youth was cut short by the Great Depression and World War II.

The early years

George Herbert Walker Bush was born in Milton, Mass., on June 12, 1924. He grew up in tony Greenwich, Conn., the second of five children of Prescott Bush and the former Dorothy Walker.

His father was an Ohio native and business executive who became a Wall Street banker and a senator from Connecticut, setting a course for the next two generations of Bush men to follow. His mother, a Maine native, was the daughter of a wealthy investment banker.