The second in a trilogy of books about the history of cricket in Guyana was launched at the Georgetown Cricket Club on Friday night with tales of malaria and its impact on the team.

‘A Stubborn Mediocrity’ by Professor Clem Seecharan follows the 2016 publication of ‘The Foundation’, both of which form part of the three-volume ‘Hand-In-Hand: History of Cricket in Guyana’. The new book covers the period 1898-1914, highlighting the battle against malaria and its effect on the national sport.

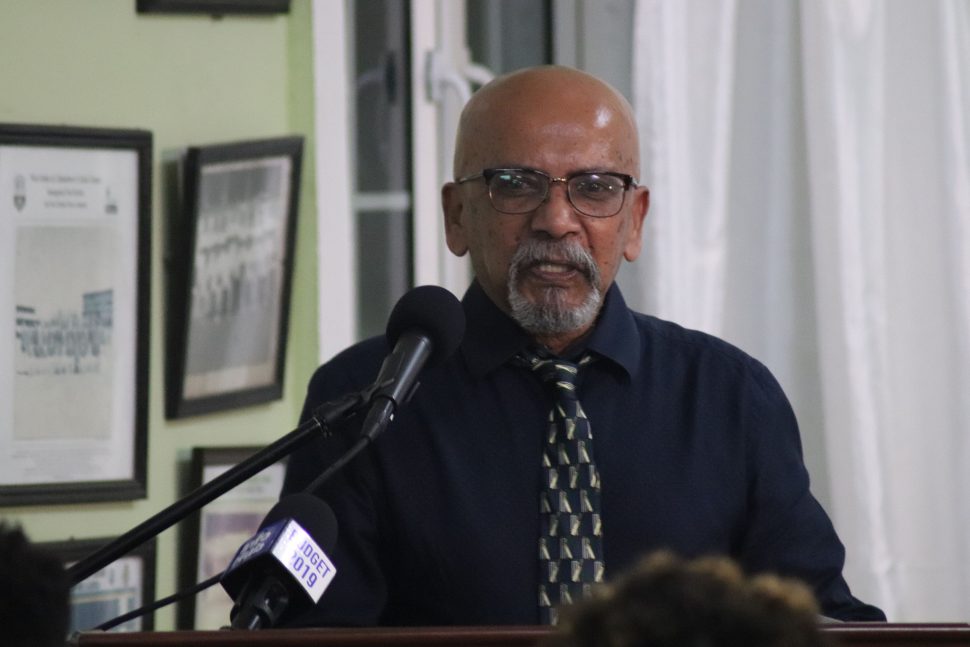

Amongst an auspicious group including Dr Winston McGowan, Dr Shivnarine Chanderpaul CCH, Lance Gibbs CCH, Roger Harper, Director of Hand-in-Hand (HIH) Group of Companies Dr Ian McDonald AA, Petamber Persaud, Chairman of HIH John Carpenter, Minister of Social Cohesion Dr George Norton, Honorary Secretary of the Guyana Cricket Board Anand Sanasie and the Guyana Jaguars team, Seecharan recounted the project, highlighting the difficulties in acquiring accurate information pertaining not just to the sport, but generally.

Carpenter, in his welcoming remarks, noted that cricket has been a part of Guyana as long as HIH has been serving the nation and the company saw it fit with the planning of their 150th anniversary, to “sponsor a thoroughly researched history of cricket in Guyana from its earliest days. In this decision, we were very fortunate that Professor Seecharan agreed and embarked on this project.”

McDonald, who is featured in the book, spoke about his good friend of over 35 years and highlighted Seecharan’s distinguished career which included a recent doctorate from the University of the West Indies and the Elsa Gouveia Prize from the Association of Caribbean Historians for his acclaimed work on Jock Campbell.

The distinguished poet detailed the dedication exemplified by Professor Seecharan, whom he said, spent long hours in the library and archives undertaking research. McDonald opined that he didn’t think anyone else could have been tasked with this duty.

In his introduction, Seecharan, who is also a History Professor at the London Metropolitan University, stated, “Cricket in Guyana is not easy because we have not kept our records. This is a great institution where we are tonight for instance, and I mentioned it about 150 times, the Georgetown Cricket Club and Bourda ground probably 200 times in this book, but we have no documentation, no records, we hardly have pictures…It is not easy to write these books, it requires a labour of love and tremendous hard work but it could not have been done without the support of this great company, Hand-In-Hand Insurance Company…the chairman said this company was founded in 1865, the same year the first first-class match was played in this region between Barbados and British Guiana.”

Seecharan urged the members of the Guyana national team to acknowledge the importance of knowing where they came from in order to understand where they are heading.

The professor noted that the British Guiana Cricket Club, which was located on Parade Ground, hosted inter-colonial matches between Barbados, Trinidad and British Guiana and explained the impact it had on the local society with people playing with the “Mammee seed (Mammea americana)” as a ball, coconut branch for a bat, bare shin for pads and bare knuckles for gloves, an anomaly that embodied the spirit of the country through one sport.

He also detailed the first female match at Mahaicony which ended in a no-result due to bad light, all the way to great players like Gibbs and Harper, stating, “we have to go back to the roots, to how the thing possessed the soul of all the people even in the interior where people were playing the game with great commitment and energy.”

The national pride in the sport does not stop there as the first test match victory for the West Indies was played at Bourda, where, Seecharan said, “We won the first test match at Bourda, the first double century by a West Indian, Clifford Roach out there, the great George Headley made a century in each match, Leary Constantine got nine wickets.”

“It’s not just about cricket, its deep in our soul, the wider framework and social environment, it was development, the game was so central to our development that the game mirrored our society, it would reflect many aspects of the kinds of struggles, our religious struggles, our ethnic struggles, class and all kinds of things that go on in society… it is so fundamental to how we are and to study this game is to almost peel back layers of who we are. It is an extraordinary undertaking,” Seecharan said.

In further recounting the history, the author recalled the population suffering from an unknown plague that hindered the country’s development so much so that we won just one regional match before the First World War.

“It is not because we didn’t apply ourselves but we were all being affected by malaria but we didn’t even know… all we talked about was the man get fever and dead, he just drop down suh and he dead…As long as malaria remained a scourge…Guyanese cricket was susceptible, Ian McDonald got to know the man responsible for the eradication of malaria as a man named Dr George Giglioli in 1940,” he said.

According to Seecharan, “one of the reason we couldn’t beat the region side started in 1893 when we won only once before World War One and I have a thesis: we didn’t know we were suffering from a terrible case of malaria which plagued us with the dampness of this coast land. Later on we found out how terrible it was and how much of us were operating at a low level.”

In the publication, Seecharan mentions McDonald’s first encounter with Giglioli in 1956. He had gone to his office in the Sugar Producers Association building on Camp Street where he was told by Giglioli, “if you had the blood count of the average cane cutters not so long ago, you wouldn’t be able to walk up the stairs to my office but they work in the field cutting cane for hours.”

“Giglioli was the first to have the idea, imagination and drive to apply DDT on a large scale thereby saving countless Guyanese…,” Seecharan said.

Between 50 to 75 per cent of all those who sought treatment at hospitals were suffering from malaria at the time as the mosquitoes that carried the disease bred profusely following the rainy season in the large numbers of ponds. At that time, the only way to control the disease was through a prolonged course of quinine, an unpopular, bitter-tasting drug.

Three distinguished British scientists met with Giglioli in Guyana. One of the scientists, Dr Alexander King, told him about the new insecticide DDT, which the Allies were using as a “secret weapon” to protect their troops from malaria. Unlike other insecticides, it was applied to the surfaces where adult mosquitoes came to rest, and a single spraying continued to be fatal to the insects for months. Giglioli asked the scientists for assistance in obtaining a quantity of DDT to conduct an experiment in malaria eradication, which would be the first in the Western Hemisphere. He was confident that this insecticide would be effective since his own research showed that the Anopheles darlingi mosquitoes were prevalent in people’s houses. He believed it would be better to attack the adult mosquitoes by spraying the houses instead of trying to destroy the mosquito larvae.

Within a month, the first 500-pound consignment of DDT was on its way to Guyana. The trial spraying of the insecticide began as soon as it arrived. A large-scale control programme commenced in 1946 on the sugar estates, and this became a countrywide campaign in 1947. It involved house-to-house spraying of the insecticide by a Mosquito Control Service which was established for that purpose.

DDT was so effective that by 1951, malaria and its principal carrier, the Anopheles darlingi mosquito, had been completely eliminated from the coastal areas. The situation was more difficult in the interior because the disease bearing mosquitoes lived in the forest. In addition, settlements were far apart and it was not easy to get to them.

Professor Seecharan dedicated the book to Dr Yesu Persaud, Dr Pooran Singh and three others.

Carpenter pitched that there could be a third volume to encompass the glory days but Seecharan said he “doesn’t know if it could hold the glory days because the glory days is a big thing in itself so I think we could probably get up to 1939.”