On the anniversary of the passing of Martin Carter, Gemma Robinson looks at the entwined work of Carter, Wilson Harris and Stanley Greaves, and the power of artistic conversations.

When Wilson Harris died in March this year it marked the end of an astonishingly creative life. Harris, the author of twenty four novels and numerous essays, was an unfailing champion of the arts of the imagination. For him, though, this was not a solitary life. It was filled with companions – when he worked as a surveyor in the hinterland of Guyana, when he spoke with friends as part of the Caribbean Artists Movement in London, with his family, and with the hundreds of people who wrote and spoke to him over his life.

Harris and Martin Carter were near contemporaries, and shared a long friendship brokered at first by A. J. Seymour through their 1940s and 50s contributions to his pioneering magazine, Kyk-Over-Al. Carter, Harris and Seymour would meet in Georgetown to discuss their work when Harris returned from his surveying projects. This was an energizing period for the arts in Guyana, as cultural clubs (such as the Working Peoples’ Art Class) and new publications grew, running in parallel with calls for political change. During the early days of the PPP, through its anti-colonial activities, Harris cut an unusual figure. Unlike Carter he was not a member of the PPP, but both were absorbed by the possibility of conversation and transformation.

Eusi Kwayana remembers Harris in a group that met on Hadfield Street:

We would talk about society and the working class and so on and Wilson Harris would sit down and listen and then he would come out of the corner and say ‘you know what is happening here in the Caribbean is a thing remarkable’, you know. He said, ‘We are going to create a culture that will astonish the world because you see these dark forces let us follow them, the anonymous forces are coming forward’.

Kwayana continues: ‘the same class forces we were talking about he would call the anonymous forces that were coming forward. He was on the same direction but with a different sort of interests, you know, and an entirely different idiom’. To the politician or political activist Harris’s words might seem too ambiguous to create social change. But they are charged with Harris’s ever-present sense that the Caribbean’s cross-cultural origins made it a crucible for new modes of living and understanding the world.

Kwayana continues: ‘the same class forces we were talking about he would call the anonymous forces that were coming forward. He was on the same direction but with a different sort of interests, you know, and an entirely different idiom’. To the politician or political activist Harris’s words might seem too ambiguous to create social change. But they are charged with Harris’s ever-present sense that the Caribbean’s cross-cultural origins made it a crucible for new modes of living and understanding the world.

Like Carter’s attention to the history of slavery in To A Dead Slave (1951), Harris looked to the past – and to what he called ‘eclipsed cultures’ to show how they mustn’t be forgotten and how they could constantly re-emerge in our own times to help us work out how to live. On a more personal level Harris worked to make sure that contemporary voices in Guyana were not silenced. He remembered standing in for Carter in the 1950s during a Georgetown literary event. Carter’s movements were restricted because of the state of emergency, and so Harris appeared in solidarity with his friend, giving voice to Carter’s poetic work at a time when his political voice was muzzled.

An atmosphere of discussion – from conversation, liming, argument, debate, to speeches – was essential to this young generation intent on charting a future out of colonialism into a new kind of Guyana. But conversations can quickly turn to division, grandstanding and discord. Carter’s 1961 series of poems, Conversations, offers a set of arguments about the appropriateness of communication: from the poet who refuses to write, to the poet who dare not keep too silent, to the poet who is forced into silence, to the poet who writes about silence. It is a sequence that deals with the corruption of society, loss of faith, and the role of poetry.

In one poem Carter writes:

I dare not keep too silent, face averted

That tells too much, it gives the heart away

Quick words distract attention from the eyes

And smiling lips are most acceptable.

Conversation has gone horribly wrong here, and communication is not about connection but about survival, distraction and protection. We might note Carter’s resignation from the PPP, the political party in which he placed his faith from 1950-1956. But the issues ran deep. In Carter’s political writing his central concerns were to confront the legacies of the plantation past, and to assert the living unity rather than division of Guyanese society. If these poems are political, they are authored by a poet who understands how easily we can be silenced by conflict. But they also prove Carter to be a poet who challenges us to speak freely and truthfully.

It would be easy to focus on conflict and failures of conversation. Writers (and politicians) are often famously at war with each other. Derek Walcott and V. S. Naipaul’s feud lasted decades and there was no reconciliation. We are told that we are living in a 21st century defined by the echo chamber limitations of social media, and the amplification of political divisions. But art also offers models for collaboration, connection and conversation that remind us how to understand other voices and different perspectives.

The friendship and connected work of Carter and Stanley Greaves is an inspiring example of this. Greaves remembers meeting Carter and Harris around 1958 at a Working Peoples’ Art Class exhibition in Georgetown. After that he was a regular visitor at Carter’s house, interrupted only by his UK studies from 1962-1968. This is how Greaves recalled their meetings: ‘I would drop by you know just to talk about whatever. I mean this thing of conversation – to have a conversation with somebody, not just a liming session. Sunday mornings I would go by Martin’. Woodbine House was another welcoming meeting place, and later when Greaves was appointed to the University of Guyana and Carter as poet in residence, their meetings widened to include Michael Aarrons, Bill Carr, and Rayman Mandall.

Greaves has spoken about Carter’s conversational style: ‘I had to work out a formula for listening to Martin. And it was just to listen and every now and again he would say something and it would crystalize in my mind and then the things that were said previously would fall into place’. Greaves explained it to Carter like this: ‘I would create a geometrical figure in my mind which would seem to illustrate what you said and that would allow me to follow your arguments’. The idea of a crystalizing moment or figure that brings understanding is a good place to start when thinking about Greaves’s pen and ink drawings for Carter’s poetry.

Greaves has spoken about Carter’s conversational style: ‘I had to work out a formula for listening to Martin. And it was just to listen and every now and again he would say something and it would crystalize in my mind and then the things that were said previously would fall into place’. Greaves explained it to Carter like this: ‘I would create a geometrical figure in my mind which would seem to illustrate what you said and that would allow me to follow your arguments’. The idea of a crystalizing moment or figure that brings understanding is a good place to start when thinking about Greaves’s pen and ink drawings for Carter’s poetry.

There are thirty-five poems in Poems of Affinity and twenty-one are accompanied by a drawing by Greaves (described as an ‘appreciation’). The arrangement was simple: Greaves said to Carter that he would like to do something and Carter agreed. The poems were finished and then Greaves began work. ‘Appreciation’ might suggest thankfulness and admiration as well as understanding. Certainly, for the later pen and ink drawings in the 1997 Selected Poems this is reinforced by their collective title as ‘Tribute to Martin Carter’. In appreciation there is also connection and assessment, so that Greaves is not only supporting Carter, but also transforming his work. Wilson Harris named this process when he wrote about Greaves’s series of paintings, Dialogue with Wilson Harris (2014): ‘As Stanley Greaves becomes involved in his symbolic interpretation of the novels, one is aware of the profound and painterly changes he brings into play’. And it is the idea of dialogue, the power of talking with one another, which fuels these transformations.

The Russian literary critic, M. M. Bakhtin, famously thought of dialogue as ‘boundless’. ‘It extends into the boundless past and boundless future’, he wrote. One way to read Poems of Affinity is as the desperate posing of questions in search of conversation or dialogue. There are questions for all. In ‘Our time’ there is social confusion – ‘Is it only just a misfortune / to be as we are; bad luck / carefully chosen?’ In ‘Too much waiting’ we have the esoterically environmental – ‘If / trees die, what happens to / caterpillars?’. In ‘Rice’ we hear practical thinking – ‘What is rain for, if not rice / for an empty pot’. Dialogue is anticipated by these questions. But the boundaries of the exchange are not enforced, and cannot be anticipated. Carter’s questions speak of hope for affinity – for closeness, understanding, kinship – in a world that the poet writes as arbitrary and fragile.

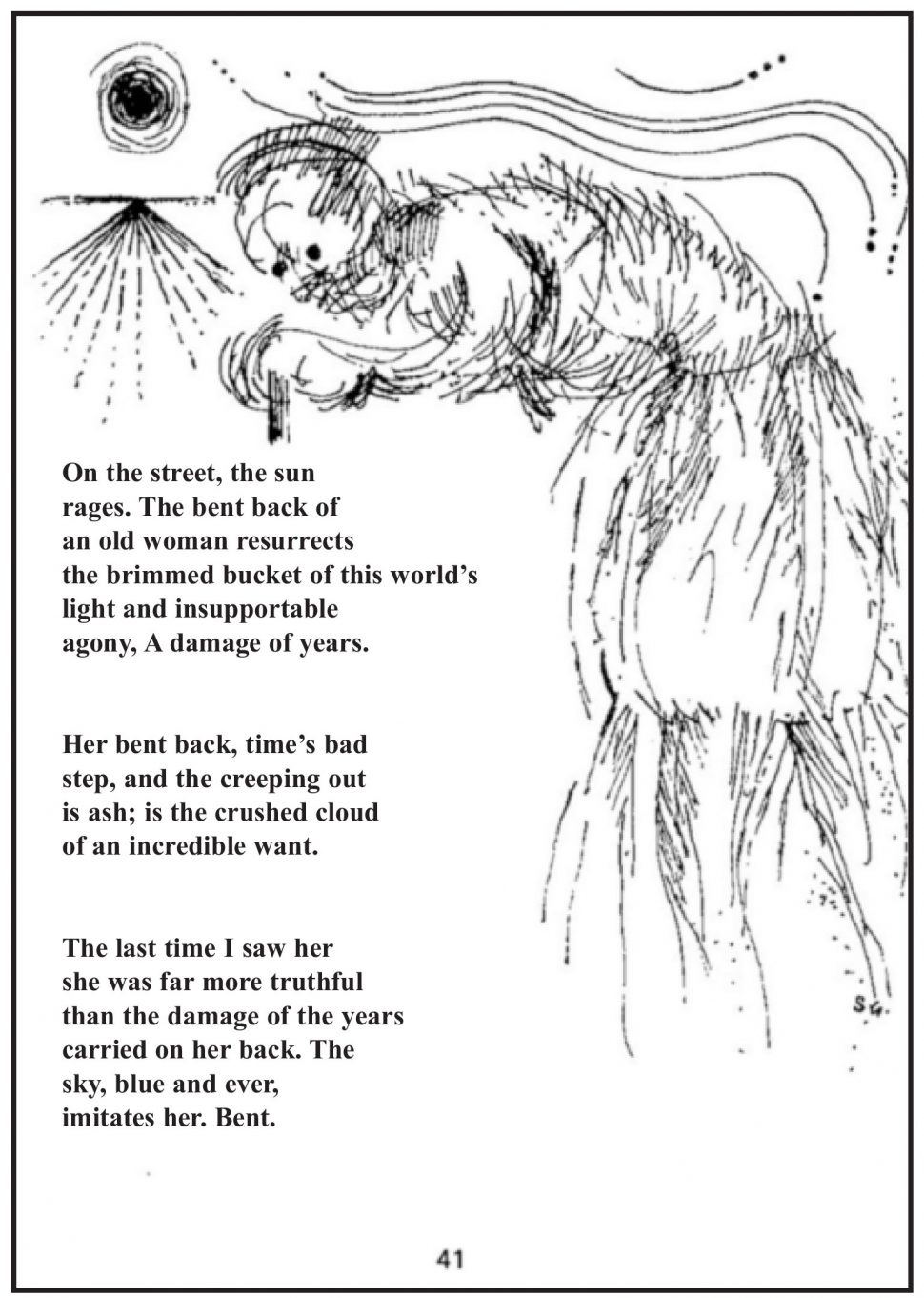

Greaves’s work is an ‘answer’ to Carter’s words, but more than that, the artworks remind us of the boundless ways that we can engage in dialogue. The drawing for ‘Bent’ is wrapped around Carter’s text, which is focused on the bent back of an old woman. It is an imagistic poem that takes a detail of daily life and contracts it down to a moment of grace:

The last time I saw her

she was far more truthful

than the damage of the years

carried on her back. The

sky, blue and ever,

imitates her. Bent.

To find truth in the face of ‘the damage of the years’ is an exacting challenge. Carter’s wide vocabulary of kinship (linking woman, sky and poet) alleviates some of the problems of visualising female pain as the means to wider human salvation. It is essential that the observing poet does not place himself centre-stage. Carter quietly registers that this is his perspective, but positions the ‘I’ in the poem to absorb the affinities between the woman and the world.

The open hatching and cross-hatching style of Greaves’s drawing seems to me to respond to this attempt to see the woman clearly. Through the open and crossed lines we see through the woman, while still seeing her, seeing the ‘damage of years’, reflecting on the meaning of ‘bent’. This openness is important and Greaves’s drawing reinforces the pain and perseverance that the poet witnesses, as well as its unknowability.

Greaves’s drawing also places us in a location with road and sun, and, like Carter’s writing, it provides a geography that is intimate and boundless. In Greaves’s Dialogue with Wilson Harris we see how attuned he is to finding crystallizing words that help create a visual world. But this is not easy. Greaves remembered his first failed attempts in the 1960s to respond to Harris’s work: ‘I wanted to paint. The problem was to find a visual language relative to the complexity of the novels’. Finally, Greaves’s way into the work came through the art of the quotation, through an artistic rather than literal dialogue.

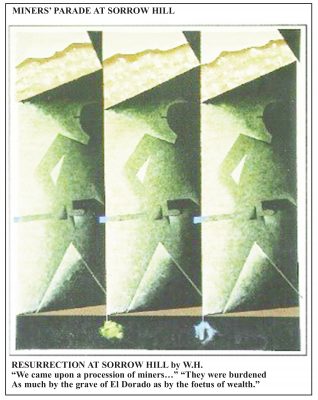

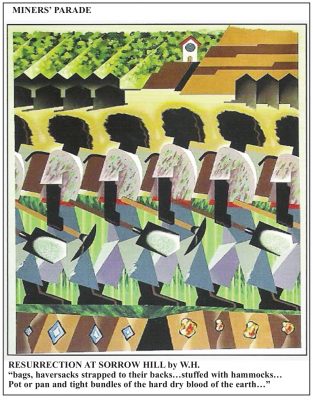

The two paintings, Miners’ Parade and Miners’ Parade at Sorrow Hill, in dialogue with Harris’s novel, Resurrection at Sorrow Hill, emphasise boundless conversation. Taking two quotations from the novel, Greaves first picks out documentary facts: ‘bags, haversacks strapped to their backs … stuffed with hammocks … pot or pan and tight bundles of the hard dry blood of the earth’. He then moves to symbolism: ‘We came upon a procession of miners … They were burdened as much by the grave of El Dorado as by the foetus of wealth’. The paintings mirror each other: men are in profile, holding spades, moving forward, but the colour palette of the first is brightly diverse, whereas the second painting is muted, using mostly shades between black, brown/green and grey.

Greaves’s idea of a ‘dialogue’ makes sense – and to me it is Bakhtin’s boundless dialogue, always generating meanings into the past and the future. We might ask: how is today’s mining linked to sixteenth century travellers who died looking for the legendary El Dorado, and what can we learn from thinking in this connected way? Dialogue is created not just between quotation and image, but also between the two paintings and between Greaves’s other ‘lattice’-effect work in ‘Canecutters’ (1977) and ‘Channaman’ (1978). As with his work with Carter, Greaves finds a dialogic method to bring into conversation the artist and the writer. It asks a lot of us. How should we act on our environmentally fragile planet? How can we live together in our intimately, often painfully, connected world?

Carter’s poem ‘Death of a Comrade’ (written in 1952 about his friend Ivan Edwards) captures the significance of conversation and boundless togetherness.

Dear Comrade,

if it must be

you speak no more with me

nor smile no more with me

nor march no more with me

then let me take

a patience and a calm –

for even now the greener leaf explodes

sun brightens stone

and all the river burns.

Carter moves from the world of human talk and action to another kind of communication and communion that we can find in the non-human natural world. He shifts perspective and finds a different kind of conversation between leaf, stone and river. Finding this will not replace who is lost, it may not even console us, but Carter makes the decision to look out from death and make connections. This creative impulse links Carter, Harris and Greaves.

In the end it may not only be their commitment to conversation that is their shared impulse, but also their ability to look beyond, to be boundless in their creative pursuits. Carter’s, Harris’s and Greaves’s work continues to ask us to look outwards from our own positions, to make connections, to find affinities. Remember too that Carter’s and Harris’s earliest work was published in the magazine Kyk-Over-Al. The word holds a bitter history as the name of one of Guyana’s colonial forts. However, the Dutch word means ‘look over all’, and it is a fitting invitation to us as we mark the entwined work of these three great artists.

Gemma Robinson teaches at the University of Stirling, Scotland and is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).