![]() A Mixtec Amerindian woman and an older White Mexican woman stand in a crowded hospital room in Mexico City. The younger woman, Cleo Gutiérrez, is in labour and the older woman, Teresa, is attempting to get her admitted. But she does not have all of Cleo’s information. Her middle name? Unknown. Her age? Also unknown. Date of birth? Same. “What’s your relationship to her,” the nurse asks, mildly agitated. “I’m her employer,” is the reply.

A Mixtec Amerindian woman and an older White Mexican woman stand in a crowded hospital room in Mexico City. The younger woman, Cleo Gutiérrez, is in labour and the older woman, Teresa, is attempting to get her admitted. But she does not have all of Cleo’s information. Her middle name? Unknown. Her age? Also unknown. Date of birth? Same. “What’s your relationship to her,” the nurse asks, mildly agitated. “I’m her employer,” is the reply.

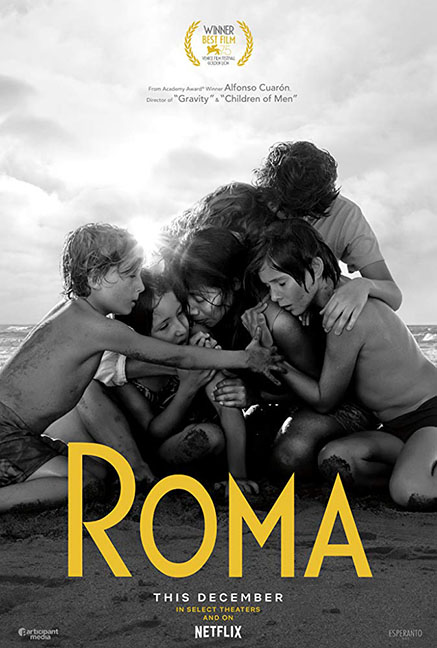

Many things happen in Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón’s new film, “Roma,” but this particular scene sticks out for me. Cleo’s pregnancy is introduced towards the end of the first act and complicates her role as a maid in Teresa’s daughter’s household. Teresa’s distress is marked by her unhappiness at her own ignorance. It’s more than Cleo’s sudden labour pains that have her overwhelmed, though. Just as Cleo’s water beaks, the Corpus Christi massacre reaches its breaking point, thrusting maid and mistress into a city overwhelmed by chaos and violence. That Cleo knows the baby’s father is somewhere in the fray only emphasises her vulnerability. That Teresa knows her place as a well-to-do elderly woman alone in the streets amidst this political upheaval makes her vulnerable is also significant. Nothing in “Roma” is accidental, but this moment feels particularly rife with context. It speaks to Cuarón’s interest in the way the private and public intersect. It confronts the realisation that someone so close to a family—Cleo lives with the family she works for—can still be so unknown.

“Roma”, when whittled to the briefest summary, is a slice of life tale. But it’s the type of life rarely given attention in mainstream cinema. We spend just under a year with Cleo from the end of 1970 into 1971, as Cuarón presents us with scenes from the life of this maid. And so, the Corpus Christi Massacre sequence is not shot as the subject of the scene but as the object. Its value is never centred, but we know it is there and we know how its existence complicates, contextualises and recontextualises the lives of the people living in Mexico in that era. There’s an elliptical nature to the way the world around Cleo is represented. The camera is almost always with her. She clears the table. She cleans the room. She runs to collect the children. But, she also chats with her friend, another maid. She goes on a walk with a would-be lover. But the world around Cleo is never our focus. Cleo is. We must fill in the gaps.

“Roma” is the story about the fullness of Yalitza Aparicio’s face as the emphatically patient and present Cleo, but it is also the story of the gaps in a life that exists in relation to the things and people around her. And the ellipsis and gaps in “Roma” feel like the surest structural recognition of its postcolonial debt. I’m not sure any story in Latin America and the Caribbean can exist without some postcolonial context. If it is not text, then it is subtext, and this story, in particular, seems overwhelmed by it. The title of the film is a nod to the Colonial Roma district in Mexico. And like many names in the Americas, it’s a mere copy of a place in Europe. Rome. The original Roma. Like everything in this region, the weight of the European context feels heavy and deliberate even when it is invisible or unmentioned. Cleo’s role, an Amerindian maid in a middle-class family, feels familiar and echoes the wistful strains of class allegiances in the region. The crisis of class and identity that exists worldwide is especially potent in our region. The history of the Amerindians, our indigenous people, is marked by their historical roots to the land and their subsequent erasure through genocide and successive cases of racism. When Cleo moves from speaking Spanish with the family she works for to speaking Mixtec with her fellow Mixtec friend (Adela, the cook) it’s difficult not to think of the scores of native languages that will not be part of posterity, doomed to be forgotten because their speakers were wiped out.

Language, of course, is central to identity and despite its use of Mixtec the film’s primary language is Spanish, the language of Cuarón, inherited from the European colonisers. And the question of language identifies itself with the issue of who gets to be storyteller and who gets to be listener in this tale. It’s a question tion that’s been following the film since its premiere earlier this year. And it’s a question that reverberated through a number of the films at the Toronto International Film Festival where the film made its North American premiere in September. It was central in Gabrielle Colette’s clashes with her husband in “Collette.” It was text in Olivier Assayas satirising of a “pseudo fiction” writer in “Non Fiction.” It pounded through Lee Israel’s tale of biographic charlatanism in “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” And it came up in discussions of the race ‘comedy’ “Green Book.”

While crying my eyes out during the climax of “Roma,” I didn’t know that the film was inspired by Cuarón’s own childhood, which he and his team revealed after the film’s premiere. Cleo is a nod to his childhood Libo. And the dysfunctional household a nod to his own tumultuous childhood. In my initial viewing, I was moved to tears by story and form rather than its context as a true tale of a real person. The knowledge that it is inspired by a real person forces a recontextualising of the film, but not one that limits it. Cuarón does not focus on the family, but on Cleo. Call it guilt or indebtedness but every frame of the film, a celebration of tableaux, a still life look at still lives, is laden with a sadness for this woman whose life is not quite her own. Women living lives that are not theirs is the film’s recurrent theme. It is so for Cleo as well as her boss Sofia (an excellent Marina de Tavira) who must come to learn that her maid is more than she appreciates as the film goes on. “Roma” looks back at a time gone by and as Cuarón has said the black and white photography vividly evokes the feeling of something in the past. But, this not a grainy or soft black-and-white which comforts with nostalgia but a precise and harsh black-and-white that immediately forces us to confront what has passed with refocused clarity. The camera observes, at a distance, lingering and full of depth. Everything here is illuminated.

The clarity of the film’s images is like a slap to the face confronting us with a past that is at times too much to bear. The camera movements echo this; the movement of the camera plays between glacial and meditative, slowly observing everything. The wide shots often place Cleo at our centre, but in the background are other things that force us to consider how she exists in relation to them. “Roma” feels, sometimes, as if it is a horror film, slowly moving to something that will distress us and like memories running through our mind unabated, we cannot stop it. When the film ends after a moment where Cleo’s value to the film is reemphasised, it is not Cuarón simplifying her sacrifice but rather complicating our own feelings about this woman who is maid, caretaker, friend, confidante and inspiration. The characters in the film, young Cuarón among them, seem ignorant of her sacrifice and value in many scenes. But the stark cinematography of the older Cuarón lays it all out on the table. He may not have known then. But he knows now. And the film feels like his reaction to that. Both tributary and penitent.

The film opens with the shot of soapy water on a tiled floor. Soon we will realise it is Cleo performing one of her duties. Cleaning up the dirt. Dust. Oftentimes dog excrement. But no matter how often she sweeps it up, sprinkles detergent, or throws the water to take away the stench; dirty things can never be returned to their original state. Mexico City is built on colonial land. And that colonial land is built on land stolen from the Amerindians. This knowledge and clarity of this informs every frame of the film even if it is rarely text. It is the sort of social/cultural/political context that is devastating, overwhelming and unavoidable. We cannot outrun or erase the past. All we can do is face it with exacting clarity and try to build a new and better life on top of it.

“Roma” was first viewed at the Toronto International Film Festival in September and is now available for streaming on Netflix.