SAO PAULO/BRASILIA, (Reuters) – The chief justice of Brazil’s Supreme Court late yesterday knocked down a colleague’s ruling that would have freed from jail former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, but said the full court will take up the contentious case in April.

Chief Justice Dias Toffoli wrote in his ruling that it would be up to all 11 justices to make a decision. The case considers whether a defendant convicted of a non-violent crime can be jailed after a first appeals court confirms a guilty verdict, which is the situation with Lula, convicted on corruption and facing six more graft trials.

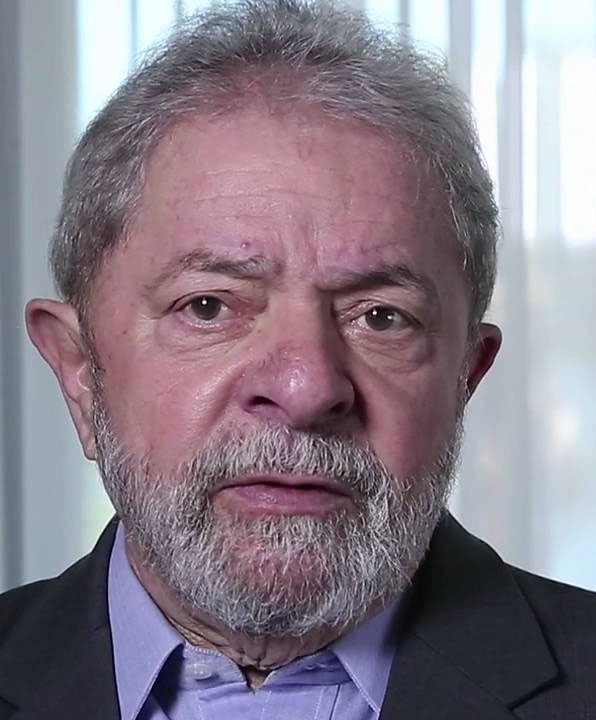

A leftist icon, Lula is one of Brazil’s most popular politicians, but is also reviled by the right, who blame him for years of corruption, botched economic policies and rising crime.

Dias Toffoli said the case would be heard on April 10, a debate that will delve into a deeper constitutional discussion that could have wide-reaching implications for Brazil’s corruption investigations and criminal justice system.

If Lula is released in April, it would galvanize Brazil’s demoralized left, still reeling after October’s election of far-right President-elect Jair Bolsonaro, who has vowed to reverse policies instilled during Lula’s two terms.

Lula, 73, was jailed in April after being sentenced to more than 12 years in prison, and faces six other trials over corruption allegations. He maintains his innocence, insisting he is a political prisoner, jailed in a bid to block him from running for the presidency.

His argument gained traction when the crusading anti-corruption judge Sergio Moro, who led the sweeping probe that helped put Lula behind bars, accepted an offer from Bolsonaro to be Brazil’s next justice minister. The president-elect takes office on Jan. 1.

Earlier yesterday, Justice Marco Aurelio Mello issued a shock ruling that suspended a Supreme Court decision from 2016 that allowed for convicts to be jailed after their sentence was upheld on first appeal.

“My conscience led me to this decision,” Mello, who voted against the court’s 2016 ruling, told Reuters. “I had to act.”

Critics have said reversing the 2016 ruling would result in the return of de facto impunity for the rich and powerful, who have been hobbled in recent years by several corruption investigations that revealed stunning levels of graft in the upper echelons of Brazilian society.

But several supreme court justices have been clamoring to revisit their 2016 ruling, arguing that lower courts have in practice made it mandatory to send non-violent convicts to prison after a failed first appeal. Won by a narrow 6-5 margin, the decision has been in justice’s cross-hairs and the subject of much constitutional deliberation that could see it revisited.

Nonetheless, leaders of Brazil’s anti-corruption drive, including Moro, told Reuters that overturning the decision would seriously damage the country’s battle against graft.

A reversal of the 2016 ruling would not only free Lula, but also release many other leading politicians and businessmen serving time for corruption.

Additionally, other powerful figures, like President Michel Temer, who is under investigation, could also benefit if eventually found guilty.

“It’s impossible to read the Brazilian Constitution … in the sense that it aims to guarantee impunity for the powerful, even when their crimes are proven,” Moro told Reuters earlier this year when asked about the chance the top court could reverse its 2016 ruling. “We are a republic, after all, not a society of castes.”

Rodrigo Janot, Brazil’s former prosecutor general who remains an influential prosecutor, told Reuters allowing convicts to remain free until they exhaust appeals deprive investigators of their best weapon in combating corruption – the ability to reach plea bargain agreements, which Brazilian law only began to allow in 2013.

“Nobody will want to turn state’s witness if they know they will not face punishment,” Janot said.