About a week ago, a story went viral online about a woman who drank a litre of soy sauce in an hour, a purported attempt to cleanse her colon and ended up brain dead. The woman, who was successfully treated and eventually recovered, was the victim of an internet scam and was possibly more susceptible to it because of misdiagnosed mental health issues. This is not to suggest that persons without those issues do not get taken in by scammers. Apparently, according to medical professionals, it happens more often than we think and just as often, people are loath to admit that they have been foolish, which allows the scams to continue.

Although they abound on the internet today, false claims of medical knowledge are nothing new. So-called quacks have been around for centuries doing great harm. The world wide web has simply allowed them to become more prodigious, while widening their target base. And while years ago some quacks actually believed what they were saying, and others did it for monetary gain, today’s scammer is mostly malicious or does it simply for laughs.

There is a saying attributed to Alexander Pope, part of which quotes: “A little learning is a dangerous thing…” and it is often taken out of context to mean people should not practice what they have learned, even if it is correct, if it is not in their field of knowledge. In fact, it means that learning – the acquisition of knowledge – should be deep and should never stop, because ignorance is that much worse. There is a caveat. We should all ensure that whatever we are learning is genuine and not the issue of malicious scammers.

Governments have a role to play in preventing scams involving medicine and can do so by promoting health literacy. It is the 21st century after all and for the most part, people, particularly those who have attained some level of education, are no longer resigned to doing just what the doctor ordered simple because he or she ordered it. Individuals want complete information and often second and third opinions. They want to be involved in the decision-making as regards their health; they are also aware that doctors are human and therefore fallible.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health literacy as: “… the personal characteristics and social resources needed for individuals and communities to access, understand, appraise and use information and services to make decisions about health”. The organisation says too that health literacy means more than simply being able to read pamphlets, make appointments, understand food labels or comply with prescribed actions from a doctor. Health professionals have a mandate to ensure that patients in their care understand their diagnoses, are aware of all of the methods of treatment so that they fully consent to what they are being prescribed, know the benefits, dangers and side effects of any surgery or medication and are au fait with dosages, drug interactions and contraindications. This does not always happen.

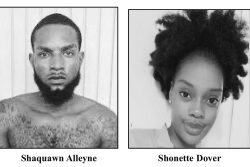

There are times when doctors or nurses might be too busy to spell out everything or might not have the time to do so, in cases where emergency treatment is necessary. However, there are instances, too, when medical professionals deliberately withhold certain information because they assume the patient might not be able to grasp it, or they choose not to have to deal with the patient’s reaction to the news, if it is not good. Sometimes, also, medical professionals relay information but use jargon, which patients are unable to follow. A possible case in point involved a breast cancer survivor, who was stricken with the disease ten years ago, treated and subsequently declared cancer free. Then suddenly last year, she presented with severe back pain, which eventually rendered her immobile. The woman died on Friday last before her story was published on Sunday. She had told this newspaper’s Women’s Chronicles column earlier last week, that she was first informed by a doctor that she had a “blockage” and later that one of her 12 thoracic vertebrae was “damaged,” and she needed surgery to fix it, but what was necessary for the operation was unavailable in Guyana. She chose to have further investigations conducted and was found to have “multiple malignant cysts” in the pelvis.

It would appear, given her subsequent death, that the cancer had returned and metastasized. It was not clear whether she was ever given this information and if she had, whether it was given in language that was easy for her understand. If not, she would have unfortunately died ignorant of what truly ailed her and may even have been unable to make mental and spiritual preparation for her death. This should never be the case.

Lack of or poor health information from professional, reliable sources is what sends the 21st century patient online where there is endless material, but a lot of it written by the malicious or by those with “a little learning”. This leads to misinterpretation, misuse and misinformation and can have dire consequences. Much more needs to be done by all health professionals but more so the public health care system to ensure the promotion of health literacy. Individuals who are educated and empowered can make informed decisions about the care that they, or others they care for, receive or can engage in such preventative measure as are available.