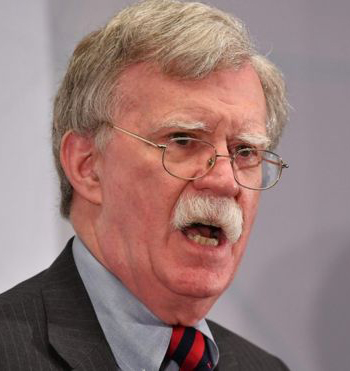

What should one make of the recent announcement by the US President’s National Security Adviser, John Bolton, outlining a new ‘America First’ policy towards Africa?

What should one make of the recent announcement by the US President’s National Security Adviser, John Bolton, outlining a new ‘America First’ policy towards Africa?

If taken at face value it suggests that the US Administration is embarking on a policy that regards the continent as a cold war playground in which superpowers vie for influence and control, irrespective of the sovereignty of the states concerned. At the same time, it implies that the decades-long US policy neglect of the continent and its cession of engagement to Europe, is at an end.

More importantly it sets out clearly a new US foreign policy model which offers benefits only to those nations that are deemed politically willing to accept its embrace.

Speaking in Washington on December 14 at an event organised by the conservative think tank, the Heritage Foundation, President Trump’s National Security Adviser set out an approach that sees Africa as a region in which the US in future intends ensuring that it has a competitive advantage over China and Russia.

In his remarks Mr Bolton said that the new Africa strategy was the result of an intensive interagency process that reflected the core tenets of President Trump’s foreign policy doctrine which is ‘to put the interests of the American People first, both at home and abroad’.

He framed the new policy not in terms of what might be good for Africa, but in relation to the national security interests of the United States, observing that “every decision we make, every policy we pursue, and every dollar of aid we spend will further US priorities in the region”. Future support he suggested will be undertaken in ways that advance US trade, counter the threat from radical Islamic terrorism and violent conflict, and ensure that US taxpayer support will be used efficiently and effectively.

He then went on to outline the criteria that the US will use for Africa.

In outline, Mr Bolton said that US aid will be targeted on “key countries and specified strategic objectives. “All US aid”, he told his audience “will advance US interests, and help African nations move toward self-reliance” with as a first objective, improving opportunities for US businesses, safeguarding the economic independence of African states, and protecting US national security interests.

The new policy will be designed to address China and Russia’s rapidly expanding financial and political influence in Africa by creating bilaterally negotiated, modern, comprehensive trade agreements that create a “fair and reciprocal exchange” between the US and African nations.

Mr Bolton also said that the US will re-evaluate its support for UN peacekeeping missions; ensure that all aid monies spent advance US interests; will insist that recipients invest in health and education, have accountable government and fiscal policy, end corruption, and promote the rule of law. He also noted that the US will revisit the ideas behind the Marshall Plan – the programme that supported the post second world war recovery in Europe – and end support for countries that repeatedly vote against the US or take actions counter to US interests.

What was striking about his remarks was Mr Bolton’s emphasis on “great power competition”, moving African states toward self-reliance and ending long-term dependency, and the centrality of outcomes that result in ‘America First’ in all US actions and policies.

Paradoxically, it comes when significant economic progress is being made by many African nations often with substantial development support from China and without the overt political conditionalities of the kind that the US is now proposing.

How the multitude of very different nations that make up the African continent will respond has yet to be seen but the Caribbean can be certain that an almost identical policy for the region is on the way.

It is an approach that is at odds with the development through dialogue approach that Europe takes in Africa and the intentionally opaque, but on the whole politically unconditional interdependent economic partnerships that China pursues. It suggests a desire to rewrite piece by piece the global rules of engagement in ways that set aside multilateralism in favour of a black and white world view that requires nations to accept US supremacy.

Read carefully what was said, substitute the word Caribbean for Africa, and it is clear that President Trump’s world view as reflected by Mr Bolton, is just as likely to be applied in the same way in future to the Caribbean and the Pacific and Indian Ocean, as it is to Africa.

It is likely that next year US thinking on its relations with the rest of the hemisphere including the Caribbean will also become clear. In one or another way it is expected that in 2019 Washington will spell out in detail the actions it intends taking against Venezuela and Cuba; its trade policy in the hemisphere; a bigger role for sanctions; and how practically it intends to respond to China and possibly Russia’s very different forms of engagement in the Americas.

US political thinking about the Caribbean has until recently been driven largely by perception of the position that individual nations have taken in relation to Venezuela. However, in October the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, and then in November the US Vice President, Mike Pence, both made clear, specifically and generally, that nations’ relations with China were driving US foreign policy.

More recently it has become apparent that the views of Marco Rubio, the Republican US Senator, on Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua, have become central to determining future US policy towards Latin America and the Caribbean. If adopted this may see beyond concern about China, the development of transactional policies towards third countries determined, as in Africa, through trade, development assistance and sanctions, that discriminate against nations unwilling to comply with US policy.

Changing US policy on Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean pose complex questions for the Caribbean as well as for Europe and the US’s allies who presently work in partnership. Most will welcome the idea of a focus on health and education, accountability, measures to end corruption, and the promotion of the rule of law. However, they know well from their shared colonial history what happens when economic benefit and decision making is dictated by one party to another.

David Jessop is a consultant to the Caribbean Council and can be contacted at david.jessop@caribbean-council.org