As a new year begins, every film critic is forced to consider the moments in cinema that burned brightest in the previous 12 months. This is not a list but rather mere ruminations on films I’ve enjoyed the most, spread across various key themes that defined the year. These are, quite possibly, my favourite films of the year but ranking them feels incidental. If forced to itemise, the top of the list might see the sobering historical reminiscences of “Roma” or the colourful moodiness of “If Beale Street Could Talk” or the nasty, angry, power-plays of “The Favourite”…but among these films which I liked a whole lot, or even loved, are moments that made me exuberant, heartbroken, devastated, inspired, and moved.

As a new year begins, every film critic is forced to consider the moments in cinema that burned brightest in the previous 12 months. This is not a list but rather mere ruminations on films I’ve enjoyed the most, spread across various key themes that defined the year. These are, quite possibly, my favourite films of the year but ranking them feels incidental. If forced to itemise, the top of the list might see the sobering historical reminiscences of “Roma” or the colourful moodiness of “If Beale Street Could Talk” or the nasty, angry, power-plays of “The Favourite”…but among these films which I liked a whole lot, or even loved, are moments that made me exuberant, heartbroken, devastated, inspired, and moved.

The power of families

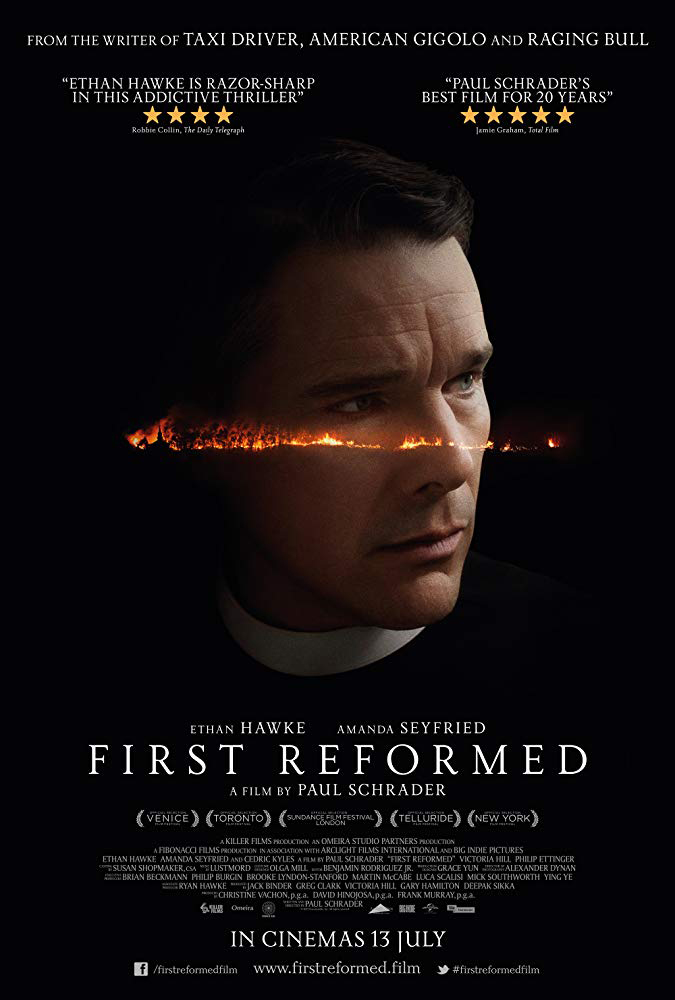

“If Beale Street Could Talk”/“Shoplifters”

“If Beale Street Could Talk” and “Shoplifters” are two leisurely paced films that build to emotional crescendos reminding us how our human existence is dependent on the families we form around us.

In the former, a young woman in 1970s Harlem depends on her family as she tries to get her fiancé out of jail after a false rape accusation, while in the latter, which takes place somewhere in the present on the streets of Tokyo, the members of a “found family” routinely shoplift to supplement their paltry income.

With “Beale Street,” director Barry Jenkins transfers the compelling power of James Baldwin’s prose to screen and with it privileges the representation of black families as the bedrock of society. The tenacity of this family’s love is not mere fantasy love, but tough and complex and inspiring. It sits comfortably alongside “Shoplifters,” where Hirokazu Kore-eda’s humanistic approach to adoption cinema patiently ekes out our empathy until it makes our hearts break. The film ambles around for much of its first half, leaving us to observe its characters. When chaos comes, suddenly and devastatingly, we are overwhelmed by how invested we have become. Both films tug at the heart. But, never lazily and never favouring the maudlin. Instead, we are moved at the tenacity of families that cannot always stay together, and marvel at parents who must sacrifice what they can for their children. Ultimately we recognise that, across eras and locales, although an uncaring world can wreak havoc on our identity, the inevitability of family will relentlessly persevere.

Humanism as super-heroic

“Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse”/“Roma”

On one hand, we have Miles, a black Latino teen acclimating to his powers as Spider-Man. On the other hand, we have Cleo, a Mixtec Amerindian whose humanistic superpower as the central saving force of the family she works for is something that escapes her. Cleo must sublimate herself, her personal life, including her grief, in order to care for the family and to attend to their needs. It is the same deemphasising of self that marks Miles’ journey towards super-heroism. “Roma” director Alfonso Cuarón’s tribute to his childhood maid is marked by melancholy as the memory film represents and then re-presents the ambivalence of the seventies in Mexico. Cleo’s heroism is not meant to be easy but is complicated as we see it come at the loss of her own identity and interiority. “Into the Spider-Verse” approaches the idea of Spider-Man’s destiny with a nuance that captures the joy and frivolity of slinging a web but the film is most powerful when it leans into the ambivalent nature of missed connections. One of the most poignant scenes features the numerous Spider-People all confessing the losses that defined their fates as superheroes and it’s a realisation of the fragility of life and its place in the expanse of superheroes that aligns the postcolonial context of “Roma” with a regretful undertone. This Mixtec maid will endure colonial exigencies, the far reaches of neo-imperialism and personal trauma, all while dealing with her own personal sadness but making a life despite it all. What’s more heroic than that?

Discontent and loneliness

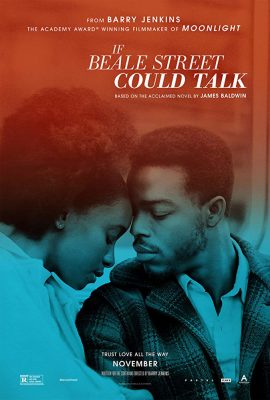

“The Old Man & the Gun”/“First Reformed”

In David Lowery’s “The Old Man & the Gun,” a man fights off his malaise about age by robbing banks and then breaking out of jail when he’s caught, all the while being pursued by a detective dealing with his own professional ambivalence. Paul Schraeder’s “First Reformed,” meanwhile, sees a lonely priest turn to alcohol and diary-writing as he experiences a crisis of faith and considers the environmental crisis.

Schraeder and Lowery are playing around with ideas of masculinity and the little things (and big things) that men do to make sense of their senseless lives. Bank robber Forrest Tucker doesn’t care about living, instead he is interested in living. But there’s a sad underbelly to his antics as if he’s searching for meaning in every job he takes, a meaning that is more illusory than actual. It’s not about the money. Instead, each job becomes another moment for this man to feel the adrenaline rush of risk. Can a life of pure abandon sustain anyone? Tucker seems more content with his philosophy of life than Reverend Ernst Toller does preaching to a congregation that does not care and living a faithless existence praying to a god that does not seem to exist. “First Reformed” interrogates religion as well as a man who must do all he can to decide whether he will give in to the darkness of despair or reach out, anew, to a world that feels chaotic and fickle. It’s a lonely job trying to keep sadness at bay, but it makes for good cinema.

History as perversion

“The Favourite”/“The Death of Stalin”

Films very often turn to the past with gloves on. Everything is pristine. Everything is detached. But for directors Yorgos Lanthimos and Armando Iannucci, the political past is prime material for the nasty and macabre. Lanthimos’ take on the last few chaotic years of Queen Anne’s rule as she juggles between two women each vying to be her favourite and Iannucci’s delightfully nasty take on the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death provide many laughs as the year’s funniest films but also offer much to think about. Both are comedies that earn their laurels for the way that they lean into things which are funny, obscene and then ultimately quite moving. “The Favourite” is a dizzyingly complex take on womanliness as masquerade as Anne and the ladies around her must utilise everything within themselves, including their very womanliness, as survival tactics in an uncompromising and unforgiving world. Even Queen Anne is not always in control. If “The Favourite” is about womanliness as masquerade, then “The Death of Stalin” is about men as fools. We watch the remaining Stalinists duelling foolishly and foolhardily for control of a nation that none of them seem particularly suited to lead. Stupidity gives way to chaos and then to murder in a kinetic array of betrayals and subterfuge. Queen Anne’s tentative reign over her country, whilst dealing with personal grief as well as personal titillation shines a fractured light on English royalty that’s macabre and morbid but counterintuitively moving and affecting. Lanthimos and Iannucci are both using anachronisms for comedic and dramatic effect but they make for refreshingly robust takes on the past, with enough curiosities to feel terrifyingly relevant to 21st century politics.

Teenagers as societal beacons

Teenagers as societal beacons

“Boy Erased”/“The Hate U Give”

In “Boy Erased,” teenager Jared Eamons is enrolled in a gay conversion therapy camp. Starr Carter in “The Hate U Give” is spending the middle years of her teenage life dealing with the aftermath of watching a police officer gun down her friend. Both are dealing with moments of trauma no teen should experience, and it’s the humanistic takes on trauma buoyed by leading turns from Lucas Hedges and Amandla Stenberg that make both films so essential. “Boy Erased” director Joel Edgerton’s reserved take on Jared’s family dynamic, his relationship with his Baptist preacher father, and his hairdresser mother, offer a surprisingly tender take on a horrifying situation. It’s the same tenderness that sees the horrific of injustice filtered through the eyes of a teenaged girl that does not devalue her youth but leans into it. Both films speak to the ways that parents must come to the rescue of their children in troubled times, but, more significantly, both speak to the ways that teenagers facing trauma are often forced to find saviours within themselves. Identity, whether sexual or racial, takes an awareness of one’s gifts and recognition of one’s strengths and limitations. At the end of both films we can breathe. Jared and Starr emerge scarred, but resilient. Our heroes have come of age. And the cultural relevance of their stories feels profound.

Politics as crucible

Politics as crucible

“Cold War”/“Outlaw King”

Throughout the film, we keep wondering what the title of Pawel Pawlikowski’s “Cold War” is really about. It’s a metaphor, surely, but what’s the signifier and what’s the signified? It’s set during the Cold War period in and around Poland, it features a couple grappling with a paradoxical sort of  love that is both hot and cold, and both love and hate but what really legitimises the title is the way the film’s cyclical developments mirror the gaps and ellipsis that mark the actual Cold War. Our existences feel elliptical when we live in fraught political times. It’s the same gaps that mark the ideas of heroism of Robert the Bruce and his allies in “Outlaw King,” as he tries to reclaim the Scottish Crown in a move that seems doomed from the outset. He doggedly continues, but, of course, a trail of blood and beheaded men haunts him. “Cold War” is precise and exact even as it is disarming and elliptical. It’s a mere 90 minutes and haunts us as we watch a tempestuous singer falling in and out of love with her stoic musician. “Outlaw King,” meanwhile, is languorous and sprawling. The love that is strongest is a love for country and the land as men fight to regain their faith in themselves and their identities. At the end of both films, the characters find themselves doomed by the politics that bore them. Some positively, others not. As much as we can whittle art down to the emotions of characters, they can never avoid the larger machinations of the political worlds they live in.

love that is both hot and cold, and both love and hate but what really legitimises the title is the way the film’s cyclical developments mirror the gaps and ellipsis that mark the actual Cold War. Our existences feel elliptical when we live in fraught political times. It’s the same gaps that mark the ideas of heroism of Robert the Bruce and his allies in “Outlaw King,” as he tries to reclaim the Scottish Crown in a move that seems doomed from the outset. He doggedly continues, but, of course, a trail of blood and beheaded men haunts him. “Cold War” is precise and exact even as it is disarming and elliptical. It’s a mere 90 minutes and haunts us as we watch a tempestuous singer falling in and out of love with her stoic musician. “Outlaw King,” meanwhile, is languorous and sprawling. The love that is strongest is a love for country and the land as men fight to regain their faith in themselves and their identities. At the end of both films, the characters find themselves doomed by the politics that bore them. Some positively, others not. As much as we can whittle art down to the emotions of characters, they can never avoid the larger machinations of the political worlds they live in.

Unreleased gems

“The Dive”/“Teen Spirit”/“Wild Rose”

In “The Dive,” three brothers must fulfil their late father’s wish as one goes off to war. In “Teen Spirit,” a young teen flirts with the idea of pop stardom from a reality show. And in “Wild Rose,” a newly released convict must juggle her two young children with her dreams of becoming a country singer. These three – as of now unreleased – films, shown at festivals in 2018, would easily make my best of 2018 list. The first two are feature film debuts from Yona Rozenkier and Max Minghella. The last is a departure from the usual work of Tom Harper. The three films coalesce in their ideas of characters dealing with familial responsibilities but yearning to fulfil their own personal idiosyncrasies. The premises all feel familiar, but the execution is what becomes essential in each case. Chances are, they may make an official appearance on next year’s list.