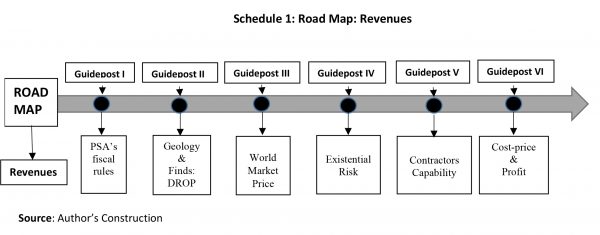

Last week’s column offered a summary outline of my Strategic Road Map for “getting and spending” Guyana’s anticipated petroleum revenues. To reinforce that presentation, I offer today a simple schematic depiction of the Road Map. The getting and spending dimensions are displayed in separate Schedules. Both Schedules are rudimentary in the sense that the goal of achieving Guyana’s transformation is represented linearly! The revenue getting Road Map is depicted in Schedule 1, and its Guideposts are discussed in the sequence indicated. The first of these, “Fiscal rules of the production Sharing Agreement (PSA),” is considered today. The others follow in the sequence displayed.

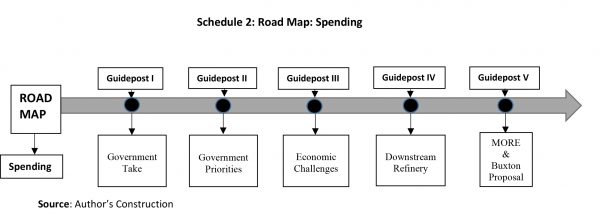

Schedule 2 similarly depicts a schematic “roll-out” of five priorities for spending Government Take (introduced last week). These spending priorities are addressed after the revenue Schedule is completed. Although both Schedules are admittedly rudimentary, they are not to be confused with either a simple “to-do list of actions” or the “detailed requirements” for a national plan.

Guidepost I: Projected Government Revenues

I have discussed the fiscal rules of Guyana’s PSA at length in the columns of Volume 3. These appeared successively during the period December 3rd, 2017 to April 15th, 2018, and again on July 12th, 2018. I do not intend to re-litigate this earlier presentation on Government Take. Guidepost I’s main intent is to establish the percentage/ratio of Government Take, which the Road Map assumes. This is pivotal for estimating Government revenue yield.

To contextualise the ratio that I employ for the Road Map is warranted, if only because this item has excited considerable local controversy. And, to escape this controversy; particularly as regards estimation of recovery cost (which is a function of both the maximum in the PSA, 75 percent, and the variable life-cycle of petroleum fields, especially offshore). I have no reliable information on this and, therefore, rely on published estimates of Guyana Government Take.

Contextualising the presentation: first, in the literature, Government Take is measured as an accounting/financial ratio (or a “fiscal metric”). Thus, Government revenues constitute a share of oil projects’ net cash flow. From an economic perspective, this fiscal metric is a gross measure. It is not “net benefit” arrived at after taking into account “government contingent liabilities for petroleum production, like environmental, social and other costs,”

Second, all PSA arrangements are risky, and cannot guarantee certainty for their intended outcomes. This occurs because of both known and unknown unknowns embedded in the petroleum industry. Therefore, revenue yield for both Guyana (Host Country) and Contractor (Exxon and partners) has to engage the rules-determining contract as a dynamic document. As a result, every PSA can be amended/changed/re-negotiated, albeit at some unknown cost. “Uncertain factors,” like technical changes, geological uncertainty, and market dynamics drive changes to PSAs! All, including Guyana’s, are “unique documents,” despite preparation of “model contracts” or templates from which they are generated.

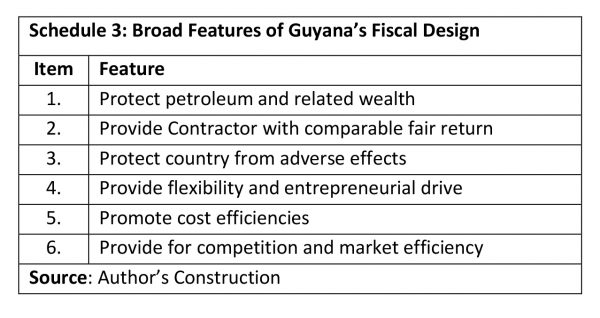

Third, PSA’s fiscal rules strive to attain multiple objectives, not only receiving revenue. In my columns on this topic, I had stressed this, PSAs do not only raise revenue, but also attend to such concerns as: protecting the nation’s wealth, protecting the country from adverse effects, and promoting efficiency. Schedule 3 (from an earlier column), summarises these wider objectives.

As is well known, the main components of Guyana’s fiscal system, include: 1) a signature bonus of US$18 million; 2) a 2% royalty; 3) cost recovery provisions and production sharing; 4) income tax provisions; 5) miscellaneous taxes and revenue imposts; 6) rental charges and fees; 7) profit- sharing; and 8) domestic market obligations (DMOs).

Government Take Calculations

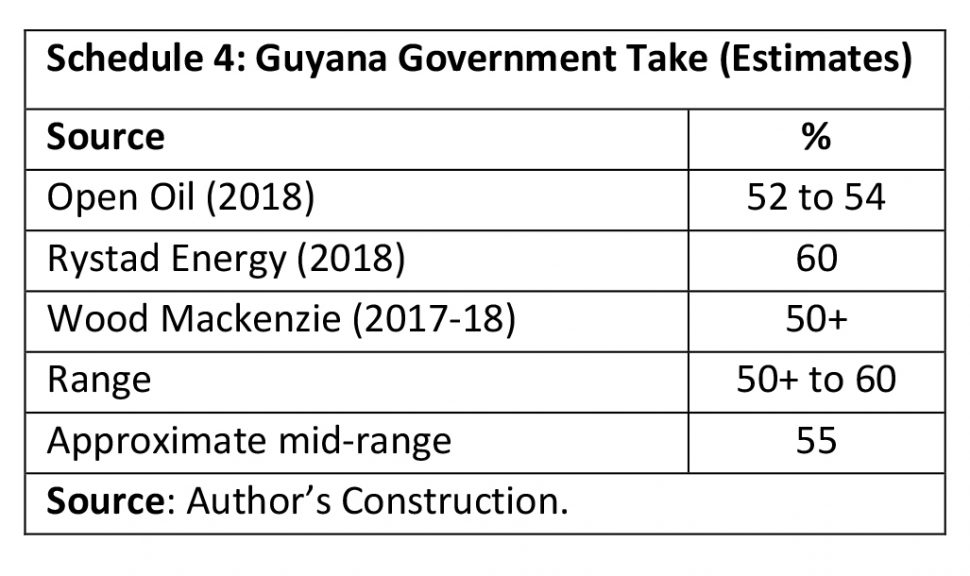

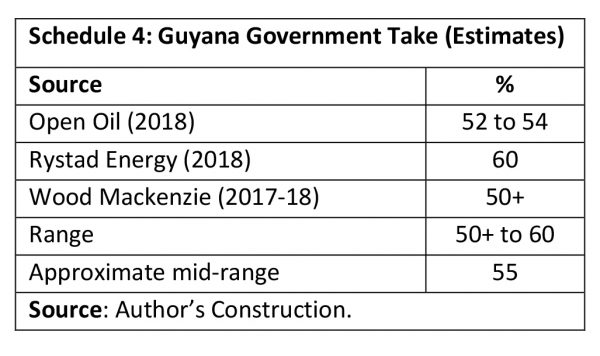

I am aware of three published calculations of expected Guyana Government’s Take. These are: Open Oil’s estimates of 52 to 54% (2018), Rystad Energy’s estimate of 60% made in 2018 and, Wood Mackenzie’s estimate of 50%+ made during 2017/2018. The range of these estimates is from 50%+ to 60% and the mid-range is approximately 55%.

I anticipate that pressures to increase this ratio will grow exponentially as Guyana strengthens its petroleum sector capacities and its petroleum activities are de-risked. New oil contracts, as well as existing ones, will consequently evolve. For the purpose of the Road Map, I shall use 55% as the Guyana Government Take percentage. Given the vigorous debates concerning Guyana’s share of petroleum revenues, this is not an unreasonable ratio to work from, at this time. Schedule 4 depicts these details.

It is worth noting Rystad Energy claims its estimate (60%) “compares with those of other frontier countries: Falkland Islands, Mozambique, Mauritania and Israel. For such countries the range is 50 to 65 percent.” Further, Wood Mackenzie also reports “revenue realisation (for Guyana) … is in the middle of the pack for a frontier area, including being in the top 10 of African countries surveyed; the top five in Europe, and fourth in the Americas”! (See July 12th, 2018 column)

Given all the above, the estimate of 55% for Guyana Government Take is clearly reasonable, and also on the conservative side.

Conclusion

Next week I consider Guidepost 2, which deals with the Guyana Finds. In contrast to the conservative stance I adopt on Government Take, I am very “bullish” on projected Guyana Finds. As I will demonstrate, this is with good justification!