(Trinidad Guardian) Gangs are responsible for the murders of at least 2,100 people in this country according to statistics from the Trinidad and Tobago Police Service (TTPS).

Last year alone, there were 179 murders categorised as gang-related. And the gang killings have continued this year.

Apart from the killings, gangs have also been responsible for numerous woundings, shootings, robberies and other violent crimes.

More than 4,600 gang-related guns have also been seized since 2010.

Gangs are a problem. And according to the statistics, it’s a growing one.

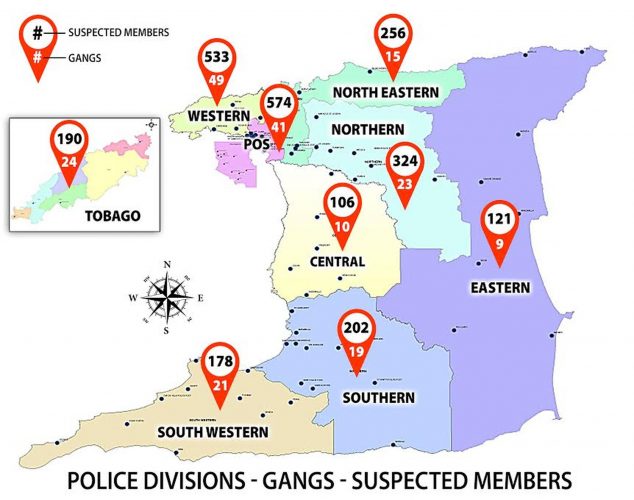

In 2006, there were 95 gangs with 1,269 members operating in T&T. Ten years later in 2016, that figure rose to 172 gangs with 2,358 members.

While two gangs in particular, “Rasta City” and “Muslim,” are the most easily identifiable in terms of names there are more than 200 now operating in the country. According to the most recent figures, there are 211 gangs operating in T&T with 2,458 members. These gangs are littered throughout Trinidad and Tobago.

So what exactly is a gang?

According to the Anti-Gang Act 2018, a gang is “a combination of two or more persons, whether formally or informally organised, who engage in gang-related activity.”

There are 46 offences listed as gang-related activities according to the First Schedule of the Anti-Gang Act including extortion, rape and sexual grooming.

The Anti-Gang Act was assented to on May 15 last year. It is described as “an Act to make provision for the maintenance of public safety and order through discouraging membership of criminal gangs and the suppression of criminal gang activity and for other related matters.”

Where did Trinidad & Tobago gang activity begin?

A 2010 study done by Charles Katz and David Choate for the Arizona State University Centre for Violence Prevention and Community Safety, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, titled Diagnosing Trinidad and Tobago’s Gang Problem, tried to answer just where gang activity began in this country.

“Of the gangs in Trinidad and Tobago, 26 per cent trace their date of origin prior to 2000, while the remainder originated after 2000,” the study said.

“Gangs in Trinidad and Tobago are typically smaller than gangs in Latin America and the United States and typically do not have linkages with gangs in other parts of the region or in other countries.

“This contrasts with some of the larger gangs in Latin America, which have connections to other gangs within their region and in the United States,” it stated.

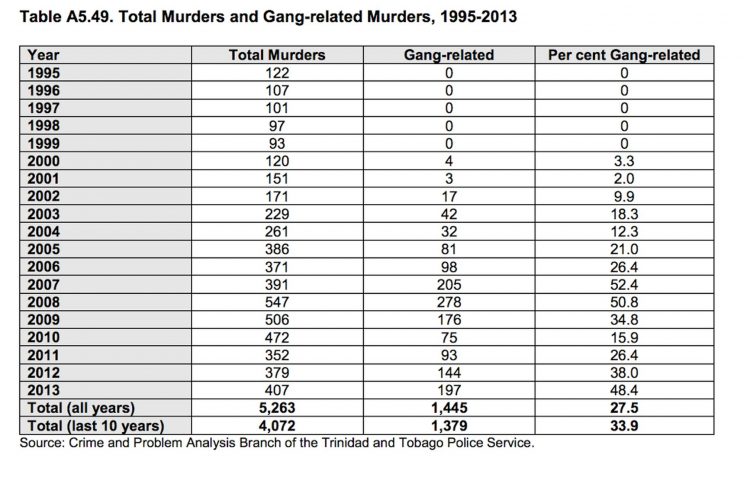

The year 2000 is a significant year because it was the first year gang-related murders entered the TTPS’ statistics. In that year four gang-related murders were recorded. It was one of only two years when the figure was in single digits. Eight years later in 2008, more than half the murders that year were gang-related. There were 278 gang-related murders that year.

The majority of gang members are said to be young adult males between the ages of 18 and 45.

“More specifically, 26.1 per cent were between the ages of 18 and 21, 25.4 per cent were between 22 and 25, and 33.7 per cent were between 26 and 35.

Only a small proportion (5.3 per cent) of the members in the sample were 17 or younger at the time of the interview, whereas 8 per cent were between the ages of 36 and 45, and 1.5 per cent were between the ages of 46 and 55,” the Katz and Choate study stated.

What is the lure of gangs?

To answer this, criminologist Prof Ramesh Deosaran believes we need to go back 50 years when “gangs were for cricket, football, liming and a little delinquency like stealing mangoes together.”

“But what happened over the years is one, you had a community infrastructure breakdown, that is the whole question of recreational facilities, the question of peer group activities like Boys Scouts and then you had the expansion of the secondary school system where quantity was more important than the quality leading to a number of fast-rising dropouts,” Deosaran told the Sunday Guardian.

“Young people being marginalised, and the young males really lost their presence in the country, you have a sharp class division where the well to do keep on being well to do and those working-class homes and working-class communities have been falling by the wayside, so now we are reaping all the deleterious consequences off of our faltering education system, community infrastructure break down and parental break down too.”

He added, “And the attractiveness now for young people are outside these institutions. The attraction is now on the corner liming with drugs, guns coming in which reinforce the gang culture, so now we have an explosion of gangsterism and even though you lock up some of them or they shoot one another, there is a long succession line behind where the supply side for gangsterism and violence is quite static, it is always there and you have to find out now more deeply, apart from punishing and sentencing and so on you have to find out where is the supply side.”

Renée Cummings, a New York-based Trinidadian-born criminologist and criminal psychologist who specialises in violence prevention and homicide reduction and provides law enforcement and violence prevention training internationally, agreed.

“Gangs are shaped by social, economic and political currents. Gangs also develop in relation to the economic development of a community. Communities layered with adverse social conditions create the context for gang proliferation because there’s a volatile combination of multiple levels of marginalisation and a collective disposition of fatalism, nihilism and intergenerational criminality,” Cummings said.

“We must also examine the labour market and how unemployment correlates with participation in gang activity. Criminality is very flexible and many young men and women move in and out of gang activity as a way to supplement their income in an economy that may not be providing many options. Economic displacement often provides the human resources gangs require. Everybody is trying to get paid,” she said.

She said the education system also played a role in the problem.

“The education system remains unresponsive to the needs of many boys and young men and continues to produce many who are unsuccessful in conventional society; supplying a steady flow of talent to gangland. The education system must embrace innovative learning methodologies and understand the impact adverse childhood experiences and early exposure to violence can have on academics, socialisation and children’s life outcomes,” Cummings said.

Deosaran said State-funded make-work programmes such as the Community-Based Environmental Protection and Enhancement Programme (CEPEP) and the Unemployment Relief Programme (URP) helped foster “gangsterism and community rivalry.”

Cummings said it is also “impossible to eradicate gangs.”

“It is impossible to eradicate gangs, but it is certainly possible to reduce gang violence using a comprehensive strategy of prevention, intervention and suppression tactics. In Trinidad and Tobago, there’s been an over-reliance on reactive policing and suppression tactics which have consistently delivered limited results. Short-sighted get tough on crime policies actually make gangs become more organised and more violent,” Cummings said.

“Devoting more attention and resources to the investigation and prosecution would send a clear message that gang violence will not be tolerated.”

Deosaran said the State needs to find a way to make gangs less attractive and improve the education system.

“A young man now going into a gang finds that having a gun is more important than five passes, so the authorities have to demystify that connection because the privileges and fame that these gang members and the leaders get are in direct competition to what the education system offers. So unless you break that connection you will always have a festering of gangs, violent gangs with drugs and guns all over the place,” Deosaran said.

“Historically, gangs have always had a powerful marketing strategy to build its membership; digital media has now extended the reach of the gang. The solution lies in understanding the ecology of violence and the inter-sectionality of marginalisation and inequality. Also, there are too many dysfunctional spaces where the police, the community and the government don’t work well together and it makes it difficult to effectively respond to violence and deliver data-driven violence prevention strategies,” said Cummings.

“Gang violence is more than a law enforcement issue, it is also a public health problem. While the police must reduce the availability of guns on the streets, government policies must decrease the number of marginalised young males.

“Policing should also be community-sensitive, community-focused and community-friendly. We also need to focus on building a strong juvenile justice system, designing evidence-based delinquency prevention programmes, truancy reduction initiatives and finding creative ways to engage boys who are dropping out of the education system.”