Winslow Craig’s work, currently on display at Castellani House, is ample proof of his genius, even though it shows only a part of his many creations. Craig is like one of the creatures from mythology, who arrive fully-formed and ready to do their job on earth. He first came to notice in 1989, when he graduated from the E R Burrowes School of Art. His graduation piece, Discovery, was a large, free-standing wooden sculpture which was so good that it was immediately purchased for the National Collection.

At the time that Craig came into public notice, Guyanese sculpture was ably sustained by the works of Desmond Ali, the Lokono artists – especially Ossie Hussein, and the Main Street artists such as Ras Iah and the late Marvin Phillips. All of these were workers in wood, and each of them added a particular flavor to Guyanese art. Ali’s large hardwood pieces reflected themes of independence, resistance, conquest and liberation. Hussein’s shape-shifting pieces done in exotic woods added a strange, new dimension to our art. The Main Street artists continued the free form style of sculpture which had blossomed in the 1980s. Craig arrived into this mix with no immediate precedents. His art was an entirely different sculpture.

In terms of his subject and themes, he may be grouped with Hussein as artists whose work reflect a religious, spiritual world view. The difference is that Hussein’s view is internal while Craig’s projects outwards. Thus, many of Hussein’s works are about entities unknown to us, while Craig’s work is about the world around us. Hussein reflects and externalizes an interior world, one of vibrations, mysteries, forces and dimensions unknown to us. His art is an inward journey to give validation to, and externalize, a whole culture and way of life. Craig, on the other hand, is very much alive to the external world and responds to it from his interior world which reflects a passion for order, a sense of justice, and redemption. An excellent example of this, is the work Ghost of Cecil, which is a response to the stupid killing of a magnificent African lion by an idle rich westerner looking for sport. In Craig’s piece, Cecil is alive and leaping at his killer. In this way, Craig comments on the sad stupidities of the material world, but he also redresses the balance in Cecil’s favour.

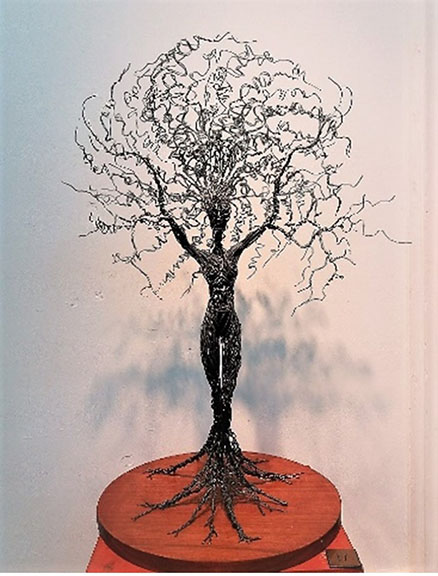

The religiousness in Craig’s art lies in the way that it reflects a belief in a higher being, one who is ready to pull us through. In many of his pieces, there is a superior helper – a helping hand – either actual or implied. In pieces such as The Unseen Helper (2000), Higher Ground (2014) and The Helping Hand (1999) the hands reach from above, while in others they cradle and protect, as Seeds (2013). This is like the Christian belief in divine grace. However, his religiousness seems to be wider and more fundamental than this. There is a strong natural element in his faith. He celebrates nature, and the mother/woman – for example, Orbs of Life (2004), The Seed of Hope (1994), Mother Nature (1990), Motherhood (1998), Motherhood II (2018) – is a recurrent motif and theme in his work. Even where a physically-recognisable woman is not present, his luxurious foliage and vegetable forms burst with life, vitality and hope.

Craig’s work also has a political dimension, as Desmond Ali’s work does. But Ali is a far more overtly political artist than Craig. Craig’s politics are ecological – not in the sense that he does indeed create works that comment on the environment, but in the sense that his politics are more concerned about the context and the way in which we live. In the 1990s, Craig’s young work had a more overtly political nature. He responded to the reining chaos of the time: it was a time of the Gulf War, millennial angst, global warming, the Rio Earth Summit in nearby Brazil, and the fall of the Soviet Union. Works such as Fighting for Global Peace (1995-96), Peace – An Elusive Dream (1995-96) are works of their time. But there is a strong vein of positivity in Craig’s art which is expressed alongside the anger. This positivity has grown as his work has developed.

Craig’s art has subtly and not-so-subtly changed over the years. His themes remain the same but have become less political and more reflective in character. The biggest change is seen in his style and his materials. Craig is a master in wood. But he has experimented with various materials. In his 1996 exhibition “Evocative” (with Dawne Isaacs at Castellani House) all of his 21 pieces were made of wood – samaan, greenheart or mahogany. Eight years later in his exhibition, “Juxtaposition” (Castellani House), mild steel, concrete, bronze, barbed wire and zinc made their appearance alongside wood. In this exhibition, also, there was one piece – Raging Season – in which barbed wire, wood glue and sawdust were the materials used. This heralded his creation of a new medium which he called “sawdoue” (sawdust and wood glue) which he began to use extensively from that time.

The current exhibition at Castellani, “A Journey & Exploration of Forms in Metal”, displays yet another material that Craig has completely mastered. This particular direction came about while Craig was on a Commonwealth scholarship at the Christchurch Polytechnic School of Art and Design in New Zealand between 1997 and 1998. Looking for a new challenge, Craig turned his attention to work in metal – especially mild steel and to a lesser extent, bronze – with the usual astonishing success. Some of his work from that sojourn are on display at the current exhibition at Castellani.

In terms of style, some of Craig’s work are angular and geometric while some are organic and rounded. The geometric pieces are austere, while the rounded pieces are rich and luxuriant. In the current exhibition, his metal works take different forms, from arcs of mild steel to intricate weaving of wire. These approaches mark not a change from one style to another but rather more of an alternation in conceptualization.

While Craig is one of Guyana’s current artists, in many ways his work is parallel to that of the great Guyanese mystic, Philip Moore. Like Moore, Craig sees his work as a transformative influence. Like Moore, he believes that art is a part of the universal mind and that his duty is to bring mankind closer to that mind and to our best selves. This view has been with him since the beginning of his art: “[…] to my mind, art is a universal language which […] touches the soul of man elevating him to a higher plain where he is in closer communion with his creator […]” (from the “Evocative” exhibition catalogue, 1996).